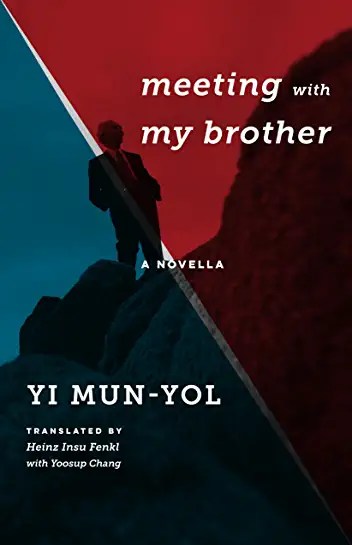

Meeting with My Brother, by Yi Mun-yol

Translated by Heinz Insu Fenkl and Yoosup Chang

(1994, translated 2017)

Weatherhead Books on Asia

(Novella)

In this brief piece, Mr. Yi explores his own past as well as some of the simplistic thinking that passes for the rationale behind the reunification of the two Koreas. The protagonist was a boy during the Korean War. He witnessed his father say goodbye to his mother and board a truck bound for the North after the invasion of Inchon. His father believed that he would return a few years to collect his family and bring them North, too, but that never happened. Meanwhile, his son has grown up to become a professor. Although he and his family struggled growing up under the shadow of his traitorous father, he never forgot him. A year ago he contacted an agent with ties to North Korea in the hopes of meeting his father. His agent fails: the old man died a few months before at the age of eighty. The son is crushed, but when he learns that his father remarried in the North and has a family of five, he decides he will contact his half-brother. Using a common dodge, he pretends to be a tourist interested in traveling to China and touring Yanji so that he can see the sacred mountain of Korea, Mt. Baekdu, and its “Heaven Lake.” There, in a touristy border town of Chinese-Koreans, the narrator meets his brother. Each brings preconceptions to the meeting. Many of them are shockingly incorrect, but the brothers also learn that they have suffered in similar ways because of their father’s politics. In addition to the drama unfolding between the siblings, Yi introduces us to two stock characters that further complicate the utopian thinking shared by the blood brothers: “the businessman” and “Mr. Reunification.”

“For several days the schoolyard was empty and the only people coming and going were those wearing red armbands. Children were able to go to school again beginning in early July through the efforts of the Socialist Women’s Alliance and the People’s Youth Alliance, but more than half the kids stayed home because they had no teachers, making it feel like summer break. Classes were self-taught or left to the propaganda departments. Trapped inside our classroom—hot and cramped, under the heavy tension of war—we grew agitated and squirmed in our seats after a few days of sneaking glances at each other while we played at self-instruction.” (29)