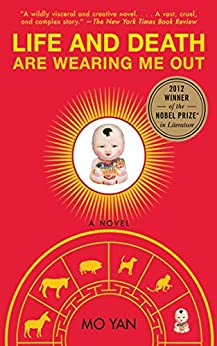

Life and Death are Wearing Me Out, by Yan Mo

Translated by Howard Goldblatt

(2006, translated 2016)

Arcade

(Novel)

Yan presents a multi-layered epic of the deaths and reincarnations of Nao Ximen, a landlord executed in 1948, who returns in various animal forms to witness the lives of his wife, children, and grandchildren, lovers, and enemies as their fates ebb and flow while China’s political ideology likewise morphs from Communism to Socialism with Special Chinese Characteristics for a New Era. Nao, who was apparently a beloved landlord, was executed as part of The Land Reform Movement. In the Buddhist Underworld, Lord Yama takes pity on the murdered man and speeds his period of reincarnation by returning him to life as a donkey. As Ximen donkey, he is able to witness the immediate consequences of his death. His adopted son, Lan Lian, marries Nao’s concubine, Yingchun, and together they raise Jinlong. They also have twins of their own, Lan Jiefang and Baofeng. Yan sets the novel in Shandong in Northeast Gaomi Township, the setting for his debut novel Red Sorghum and the touchstone for all his subsequent writing. Yan is thus able to catch us up on the progress of some of his memorable fictional characters from the past while taking us into the future. He also introduces himself directly into the narrative, sometimes as a foolish, frog-like busy-body, sometimes as that fellow who, because he pursued a career in journalism, could hire the otherwise unemployable. Yan also references his other novels as a way to add verisimilitude to the outrageous twists and turns of Life and Death are Wearing Me Out. For example, he introduces characters from his other novels and many times offers proof that what he is telling us is true by asking us to compare the events to what he wrote in other works of fiction. As with Red Sorghum, Yan’s writing is satirical, heartbreaking, and rich in the darkest of touches of humor. As Nao Ximen dies and returns as an ox, a pig, a dog, and a monkey, he is slowly able to distance himself from his scalding anger at having been betrayed and murdered. However, he also becomes less and less human, making it more difficult for the readers to find a narrator and the thread of the story. Yan invents a number of solutions, the most successful being that one character, Lan Lian, eventually recognizes his adoptive father in each of the animals—his purity of soul and focus on justice allows him this visionary power. Lan Lian, his face awash in a large blue birthmark, is the great shame of Gaomi Township, as he alone refuses to join a commune, vowing instead to hang onto his identity as an independent farmer. His stubborn commitment to independence makes him an outcast and costs him the love of his wife and family, but in the end, while all his neighbors have ridden high and low on the wheel of China’s fortunes, he emerges a hero of the modern age, a man whose personal desires once again align with the ideology of 21st century China. It is a hollow victory for Lan, as by this time he can barely work the farm and every square inch of it holds the grave of some family member or some reincarnation of his beloved landlord, Nao Ximen.

“Much as I hated being an animal, I was stuck with a donkey’s body. Ximen Nao’s aggrieved soul was like hot lava running wild in a donkey shell. There was no subduing the flourishing of a donkey’s habits and preferences, so I vacillated between the human and donkey realms. The awareness of a donkey and the memory of a human were jumbled together, and though I often strove to cleave them apart, such intentions invariably ended in an even tighter meshing. I had just suffered over my human memory and now delighted in my donkey life. Hee-haw, hee-haw — Lan Jiefang, son of Lan Lian, do you understand what I’m saying? What I’m saying is, when, for example, I see your father, Lan Lian, and your mother, Yingchun, in the throes of marital bliss, I, Ximen Nao, am witness to sexual congress between my own hired hand and my concubine, throwing me into such agony that I ram my head into the gate of the donkey pen, into such torment that I chew the edge of my wicker feedbag, but then some of the newly fried black bean and grass in the feedbag finds its way into my mouth and I cannot help but chew it up and swallow it down, and the chewing and swallowing imbue me with an unadulterated sense of donkey delight.” (20)