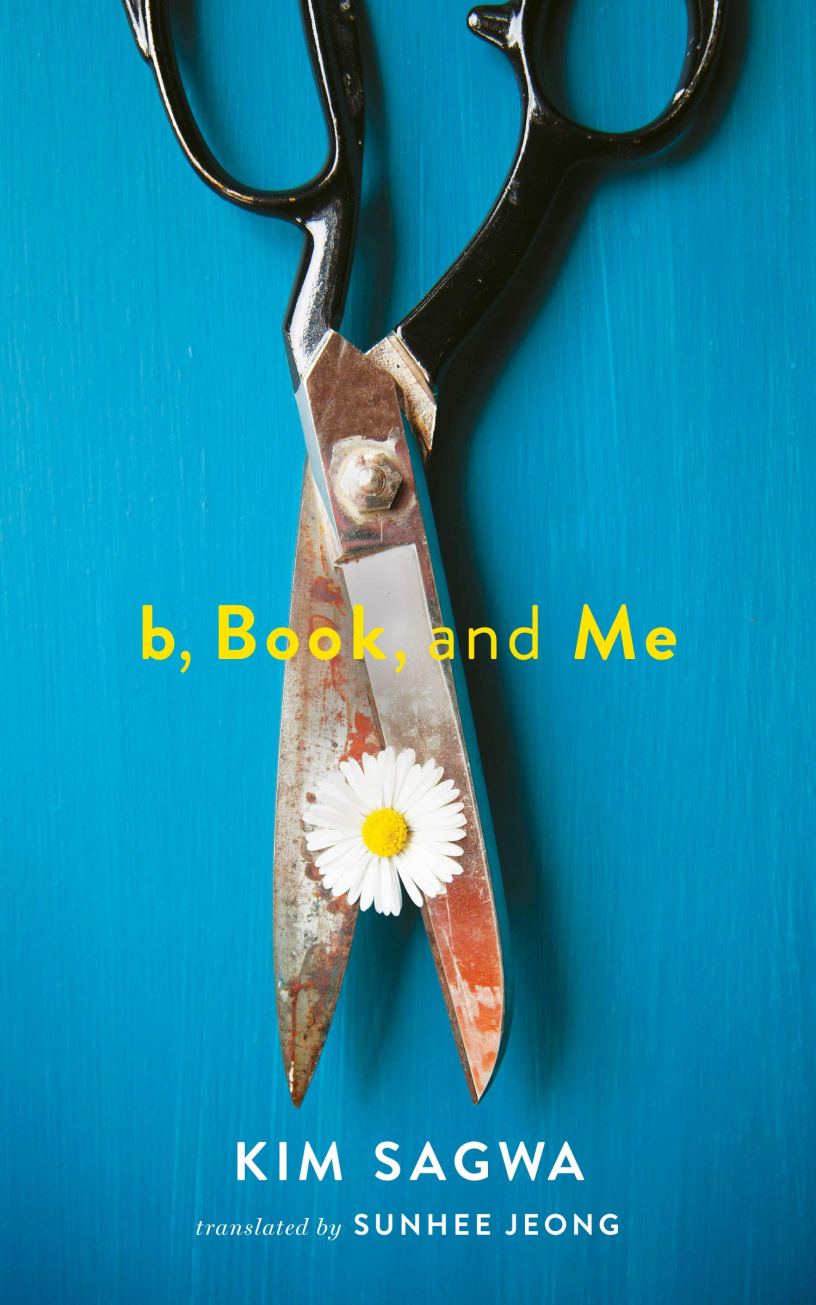

b, Book, and Me, By Kim Sagwa

Translated by Jeong Sunhee

(2011, translated 2020)

Two Lines Press

(Coming of Age Novel)

b, Book and Me is promoted as a young adult coming-of-age novel; the metaphor-rich Korean title, Butterfly Book, signals growth through transformation, rebirth, and reinvention. And certainly the reader will find many tropes of the young adult genre: the female protagonists are in middle school, where students graduate at fifteen or sixteen years of age; they are outcasts and bullied; one is poor, one is well -to-do. However, the world Kim creates is relentlessly bleak and comfortless. The young are cut off from the protection, guidance, and love of adults. The students, the entire school body, the town itself drif along with a sense of pointlessness and unfulfilled yearning for meaning. The town is a backwater, far from Seoul, a coastal town no one wants to visit, where many stores are named for Seoul: “Seoul Bakery,” “Seoul Fashion,” “Seoul Cafe.” The population either aspires to escape the town to live where life is truly lived — in Seoul — or delude themselves into believing that they are where they want to be. Short of that, all the characters fantasize about annihilating themselves or engage in some manner of self-destructive thinking. Like many Korean novels about school children, the novel wades into the crises of bullying, but in b, Book and Me, there is no escape and no hope. Teachers turn a blind eye to the violence and graduation will only lead to only more suffering, more isolation, and more despair. The protagonists, Rang and b, linger in a perpetually empty coffee shop called “Alone,” drinking lattes and chatting with a disillusioned Seoul investor and “Book,” a man who hides from society and lives only through reading book after book after book. Rang and perhaps the reader may feel empathy for b, whose life is complicated by her family’s poverty, yet b is also so explicitly clear about the degree to which she loathes her sickly younger sister, whom she blames for their poverty and the way she monopolizes her parents’ attention, that it is hard to feel pity for her. Rang “manages” the bullying by nameless boys by tolerating a level of sexual abuse that leaves her feeling more like an animal than a human being. Although the novel climaxes in a righteous act of revenge, the moment does not lead to a sense that the two girls will emerge from the darkness that engulfs them like the ocean.

“There’s a painting I once saw,” Book said, “a painting of a man without any clothes on. With both hands he was holding a bathroom sink and his head was shoved into it. The man was trying to climb into the sink. I was so surprised when I saw it, because that man was me. I try to get into books like that man was trying to go into the sink drain. Yes. I want to go inside books. That’s my dream. I want to go in and never come out.” (91)