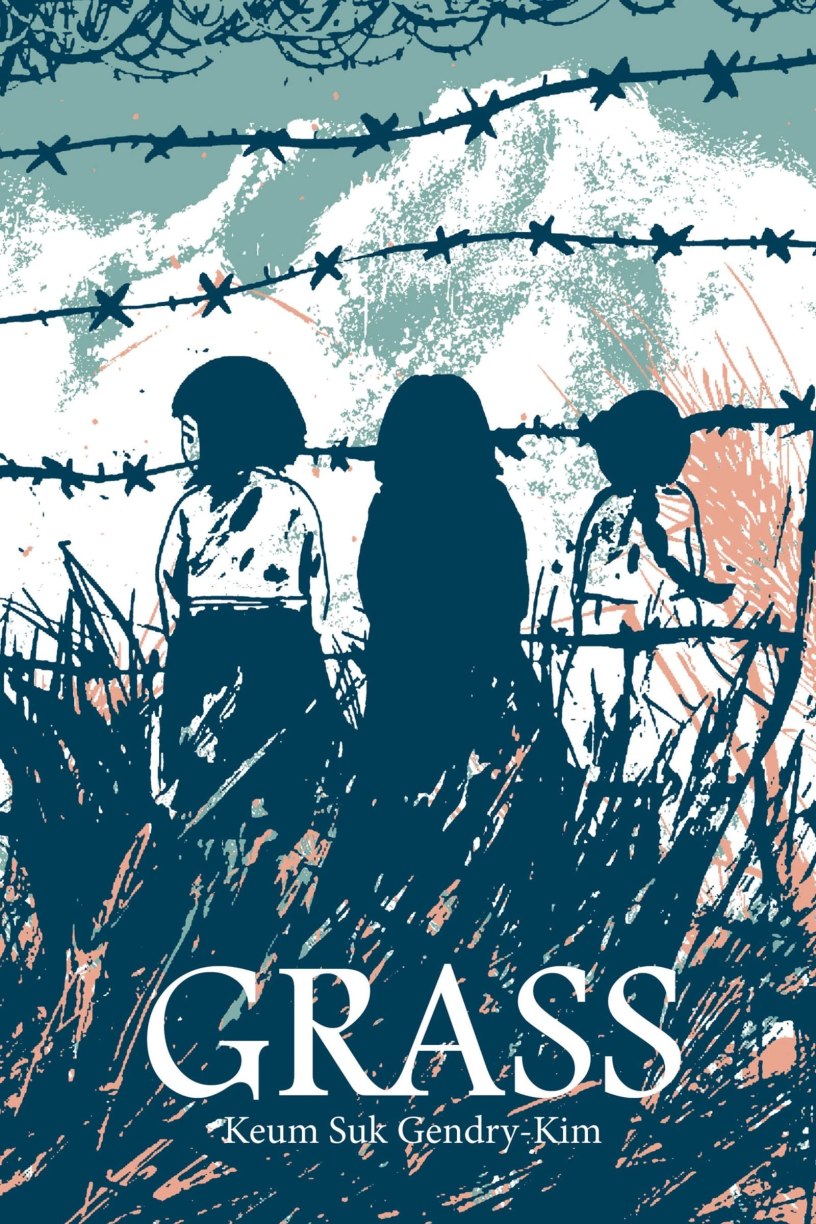

Grass, by Keum Suk Gendry-Kim

Translated by Janet Hong

(2017, translated 2019)

Drawn and Quarterly

(Graphic Novel)

Grass is a graphic novel about the plight of comfort women, Korean teenage girls who were kidnapped by the Japanese and forced into sexual slavery. Keum focuses on the story of one of the last surviving victims, Lee Okseon. Lee came from a large family in the country. Her parents were unable to feed her, so they sold her to a couple who claimed they needed her to work at a restaurant in a distant city. In return, they promised to send her to school. Instead, the couple overworked and abused the child. She flees and is caught by Japanese soldiers who send her and other Korean girls to an airfield in Yanji in China to “serve” soldiers and conscripts. Keum injects herself into the story: we see her meet Lee in the “House of Sharing,” a home for women who were abused by the Japanese during the war. Keum draws herself as quite young; initially, it seems that she is a curious granddaughter visiting a beloved relative. Lee reveals stories of her life before her abduction fairly openly, but Keum struggles to get more out of the old woman. For example, on one page she draws panel after panel of her listening as Lee rages against her captors and the Japanese, Chinese, and Korean men who abused her. Over time, Lee tells more stories, explaining how a friend became pregnant in the camp, how treatment for syphilis made her sterile, and how one thirteen year-old-girl who “served” the officers may have escaped. The tales are horrifying and endless. Eventually, the war ends. The Japanese managers of the camp flee, but Chinese civilians capture them and beat them to death. Soviet troops sweep through the area; rather than liberating the people, Lee describes how they raped and murdered any woman they encountered. Lee sets off with survivors from the camp. They have no money, but no one will provide them shelter because they know who they are and what they did. They decide their best chance to survive is to split up and go begging. Lee almost starves to death but remembers that there was one kind man in the camp who gave her food. She recalls the name of the town he said he was from and walks there. Remarkably, he is delighted to see her and though he is a Korean who collaborated with the Japanese and he knows that she cannot have children, he marries her. Unfortunately, four days later he joins the Korean Volunteer Army to fight against the Japanese with the Chinese Communist forces. When her husband fails to return, she assumes the worst, but as a filial granddaughter, she devotes herself to caring for her husband’s parents. Ten years later, by accident, she discovers that her husband had survived the war and remarried. As tragic as this first marriage is, it is only a prequel to a fifty year marriage to a miserable alcoholic. As Lee’s story comes together, Keum takes us along as she tries to retrace the old woman’s path. Here and there a building remains, but her childhood home is long gone and the officer’s quarters at the old Yanji airport are scheduled for demolition. There are other efforts to erase the past that Lee actively rails against. Reunited with her family, she discovers that they grew up believing that her parents were against Lee leaving the family and refuse to believe that their parents could have sold her. Lee is also shown on television as she protests the 2015 agreement between Japan and South Korea declaring that the situation of the Korean comfort woman was officially settled. Keum’s writing is spare and direct, as are her black and white drawings, yet some of her most powerful effects come from her use of silence as she presents wordless panel after wordless panel. It is these moments that remind us that the real work behind this project is rooted in listening to the words and silence of a survivor.