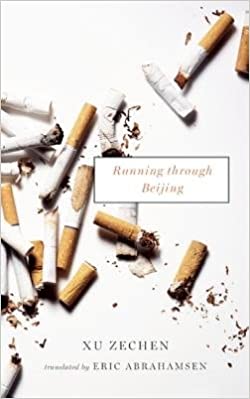

Running Through Beijing, by Xu Zecheng

Translated by Eric Abrahamsen

(2008, translated 2014)

Two Lines Press

(Novel)

Xu takes us into the underground economy of Beijing, a black market that runs at a furious and never-ending clip, fueled by an interminable influx of the poor twenty-somethings who come to the big city to make a fast buck. When we meet Dunhuang, he is just released from a three-month stint in prison for his involvement with a fake ID scheme. Homeless, friendless, and penniless, he returns to the streets of the capitol where he begins a new hustle selling pirated DVDs. A clever entrepreneur, he finds ready customers in unexpected ways. A practical man, he wants to sell soft and hardcore pornographic videos as these will bring him the most profit, yet he discovers that his most reliable market can be found at the Beijing University, where on any given weekend thirty or forty film students might need copies of art films. He travels in circles where he is likely to encounter poor graduate and doctoral students, fellow hucksters, and their erstwhile girlfriends. Xu paints a desperately grim portrait of a city constantly overwhelmed by sandstorms and where the forces of the right–the police and prison guards–often seem more corrupt and destructive to the populace than the ranks of low-level criminals and prostitutes. It is also a world where just about anything can be faked or pirated, yet the hero, Dunhuang, is more often than not compelled to do the right thing and adhere to his own moral code. His perseverance, inventiveness, and sense of duty never falter. The language is profane, and Xu does not hesitate to chronicle Dunhuang’ romances and his sex life, but in the end, one feels closer to the great city than ever before.

“Rarely was May in Beijing so grave and humorless. Then the winds ceased, like a hundred-meter sprinter halting in his tracks, too sudden for the Meteorology Bureau to keep up. The fine sand hung in the air, turning heaven and earth a dusky yellow, and the pollution indicators went through the roof. The news instructed everyone to stay indoors, and to good effect—Dunhuang worked every day, but even in the sheltered corners sold no more than a couple of DVDs. Sales this poor were unusual, but then again maybe not unlikely—once again there was word of a clampdown, and this time it seemed real.”