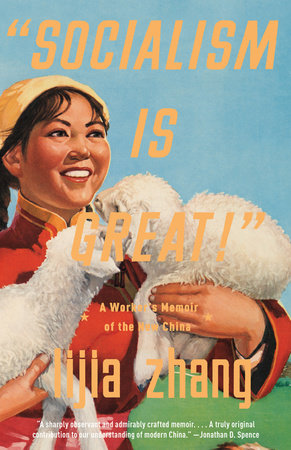

Socialism is Great! A Worker’s Memoir of the New China, by Zhang Lijia

(2008)

Atlas

(Memoir)

Zhang opens a window onto her personal experience as a student, factory worker, and nascent journalist, covering a period of time from roughly the 1970s through the 1990s. Along with her friends, she was preparing herself for college, but when she was sixteen her mother quashed those plans. Her mother had managed to secure work in a major factory that produced, among other things, intercontinental ballistic missiles. The job was exhausting and dangerous, but it allowed her mother to raise her children in a safe environment where all their basic needs would be met. In her early fifties, her mother took early retirement partly because of the health issues she suffered because of the lack of PPE in the area she specialized in, but mostly because she wanted to bequeath her membership in the factory to her teenage daughter. The mother wanted to give her daughter the security of an “iron rice bowl,” but Zhang was devastated to see an end to her dreams. She describes the work culture of the factory, the seriousness with which she took her assignment as a calibrator of high-pressure valves, and her awakening to the reality that much of her workday is spent in loafing and political posturing. She quickly learns that she can smuggle in books to work and read them under her desk, spending hours at a time reading western novels in Chinese and studying college-level cram books she picks up in used book stores. Zhang proves to be a determined autodidact. She never stops studying. She decides her best chance to escape the factory and expand her knowledge of the world is to study both journalism and English. She also becomes involved with a series of men. One stands out as particularly critical of the Chinese government. His heady talk inspires Zhang and she becomes a student of politics. She soon realizes that he has no intention of marrying her and the affair ends, but her political fervor remains. In 1989 she organizes a protest at the factory, the largest protest in Nanjing in support of the Tiananmen Square protest, and is arrested. Through all her experiences, she continues to pursue a career as a journalist while also improving her English fluency by joining clubs, an activity that buoyed her intellectually and socially. She also earned good money translating western books into Chinese. Eventually, Zhang leaves for England, where she finally earns a degree, and then returns home to become a journalist and writer. Zhang’s characterization of her mother, grandmother, and sister is lively and illuminating; they are starkly conservative beings, focused on keeping a low profile, avoiding conflict, and maintaining the status quo. Critics remark that Zhang spends too much time developing her sexual awakening and her illicit love affairs. However, her description of romance in China in the 80s and 90s is a study in an altogether unique culture where privacy is virtually nonexistent and women and men are under extraordinary pressure to avoid dating until after age twenty. Her candor about human desire in a communist state is eye-opening and fearless: she describes her horror at becoming pregnant as well as the clandestine society of abortionists.

“I knew some people already mocked me behind my back as “neo–white collar”—a white coat, like a doctor’s, was our new uniform, yet I had the status of a manual worker. Even my colleagues didn’t really consider me one of them because I was a daxuesheng with a degree. Like my father, I was another ‘Kong Yiji,’ a misfit who belonged neither to the long-gowned intellectuals nor the short-sleeved coolies.” (174)