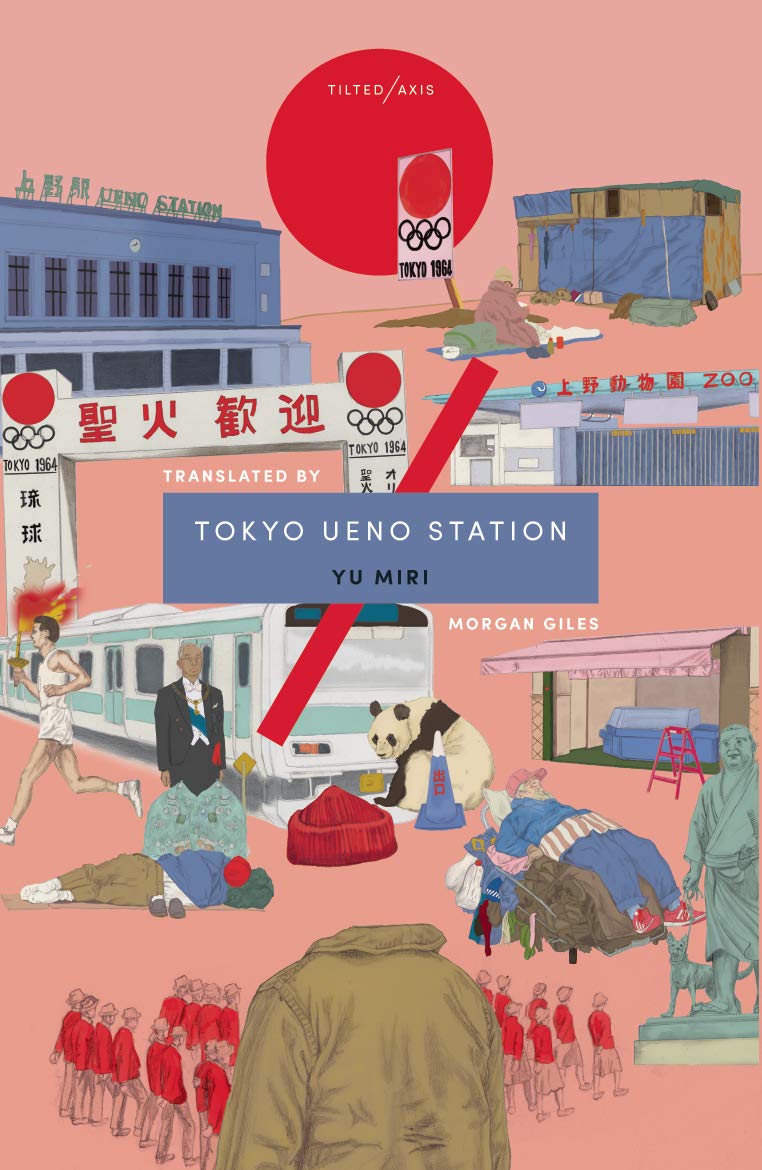

Tokyo Ueno Station, by Yu Miri

Translated by Morgan Giles

(2014, translated 2019)

Tilted Axis Press

(Novel)

Ms. Yu was born to Korean parents in Yokohama. No doubt her identity as a Zainichi has strongly influenced her writing. She is known for her experimental writing and strong political criticism of the Japanese government. Like The Memory Police, Tokyo Ueno Station is a “post-tsunami” novel, a memorial to the victims of the historic double disasters and a critique of the government’s failure to respond adequately to the threat and the consequences of the 4/11/2011 earthquake that devastated the Tokohuran coast. Yet Yu’s criticism is much broader. She achieves her wide-ranging critique of her nation’s soul via her choice of narrator and setting. The narrator is Kazu. He was born in 1936 in Fukushima, the year the Emperor was born. From the start, the coincidence was not propitious; as his parents and grandparents remind him, he never had any luck. He worked on the shore from his early youth to help his family eke out a living. When he marries Setsuko, they have three children together, but in order to put food on the table, Kazu lives far away in Tokyo and Sendai working as a low-level construction laborer. He even works on the construction of several arenas for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. In thirty-seven years of work, he estimates he has been with his family for less than a year. There is happiness: his son Koichi is born on the same day as the Emperor’s son, an auspicious coincidence! But fate is cruel. His son, Koichi, dies at age twenty-one, found dead in his dorm room on the day of his graduation from college. His wife dies soon after. Kazu continues to work, sending money now to his parents and his daughter’s young family. In his late sixties, he feels he has become a burden to his daughter and granddaughter, so he writes a goodbye note and heads to Tokyo Ueno station, where he joins the aging homeless population. After several years of “sleeping rough,” Kazu dies, and now existing as a ghost, he tells his life story. Yu tells a heartbreaking story of an individual family’s suffering. She also uses the physical and cultural geography of Ueno Station to bring to life Japanese history and the hypocrisy of its government. The imperial palace is above Ueno Station Park. Each time the emperor’s family visits the shrines and cultural centers in the park, notices appear on the cardboard and tarpaulin shacks of the more than six-hundred aged homeless people, commanding them to vacate the park the next day. The park is also home to a Museum of Western Art and the Statue of Times Forgotten, a representation of a mother and her two young children searching for shelter during the fire-bombing of Tokyo in 1945. On that day, the US targeted the lower-class residential section of the city. Because of the large pond in Ueno Park, it was somewhat protected; survivors buried nearly eight thousand victims of the bombing in the park. The park is also home to the Kaneiji Temple, a statue of Saigo Takamori (the “Last Samurai” who spearheaded the Meiji Restoration), The Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of art, The National Science Museum, the Ueno Zoo, and the Bentendo Shrine, built to honor the Goddess of Good Fortune. Kazu haunts these sights, both when he was alive and after his death. He watches citizens, listens to their banal conversations, and expresses frustration when he realizes that the reason behind the efforts to drive the homeless out of the park is so that politicians can sell the International Olympic Committee on the idea of allowing Tokyo to host the 2020 Olympics. Yu also devotes a significant portion of the novel to providing the backstory of Kazu’s family, who were part of a Buddhist sect called the “True Essence of the Pure Land” followers who were harassed for their beliefs by the people of Soma. The text is a little over one-hundred and sixty pages long, but reading it is like drifting through layers of an archaeological and spiritual trench cut through the heart of a nation.

“On the south side of Tenryu Bridge, along the metal fence around Shinobuzo Pond, there stood some huts which were little more than cardboard enclosing a small space lined with more cardboard and blankets. Tents were not allowed to be put up around Shinobuzo Pond. Previously, when the management had been more lax, people had fished and caught ducks and cooked together around an open fire here, but now the police and park officials made rounds, and the residents of the block of flats nearby would call to make complaints to the council.” (136-137)