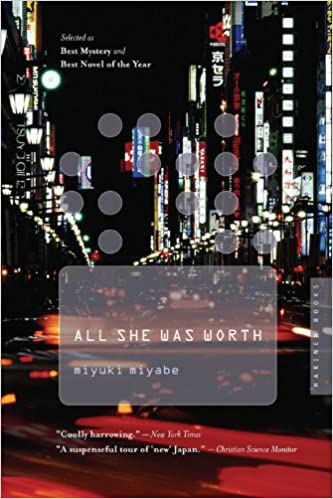

All She Was Worth, by Miyabe Miyuki

Translated by Alfred Birnbaum

(1992, translated 1996)

Mariner Books

(Crime/Mystery)

Miyabe is a successful crime novelist; ten of her books have been made into movies. As in Hiraono Keichiro’s A Man, Miyabe’s subject is a Japanese citizen who has gone to great lengths to disappear herself and reemerge in society under a new name. In this case, the criminal is a woman running from debts and loan sharks, men who destroyed her family and trafficked her in the sex trade. To escape her fate she targets a woman like herself who is without a family and in her late twenties; she may have swapped family registers with this woman–or she may have murdered her. Ms. Miyabe introduces a likeable and tenacious police detective, Honma Shunsuke, who, after his wife was killed in a car accident, is raising a ten-year-old son on his own. He is also on leave from the Tokyo police force until he recovers the use of a leg that was badly damaged in a shooting. A distant relative contacts him on a private issue: after an argument about a credit card, his fiance has disappeared. Can Honma find her? Because he surrendered his badge at the start of his leave, Honma is limited. However, he can count on calling in favors owed by a colleague, Detective Funaki, and rely on the support of his neighbors Isaka and Hisae, who watch out for his son during the day and help him puzzle out the case. He also enlists the help of the mechanic Tomatsu, who went to school with the victim and who may still carry a torch for her. Miyabe takes us deep into the world of the victim of the identity theft, Shoko Sekine, and also the possible murderer, Kyoko Shinjo. Both of the women are in the positions they are in because of debt. One of the highlights of the novel is that Miyabe introduces a personal bankruptcy lawyer into her novel, a device that allows the author to expose how aggressive, unregulated lending in the 1980s and the widespread, almost inescapable marketing of credit cards, created traps for parents and young people who wanted to take advantage of Japan’s boom. She explains that this explosion in the lending and debt recovery services spawned tier after tier of lenders who would charge exorbitant interests and essentially created the legal cover for the loan sharking branches of organized crime. Miyabe, through Honma and the personal bankruptcy lawyer, makes a strong case that the Japanese government is failing to protect its citizens from the predations of unregulated lenders. As he listens to how easily young and old Japanese were caught up by the go-go consumerism of the 1980s and then overwhelmed by crushing debt in the “Lost Decade” of the 1990s, Honma struggles with his preconceived ideas about personal responsibility, the social contract, and the roots of evil.

“These companies just lend and lend all over the place–so long as they’re not the ones holding the bag in the end, and in the meanwhile they’re collecting all that interest. Usually it’s the individual, anyway, not the bank or the loan shark, who loses out. It’s a sort of upside-down pyramid, with the debtor at the bottom supporting the lenders.” (233)