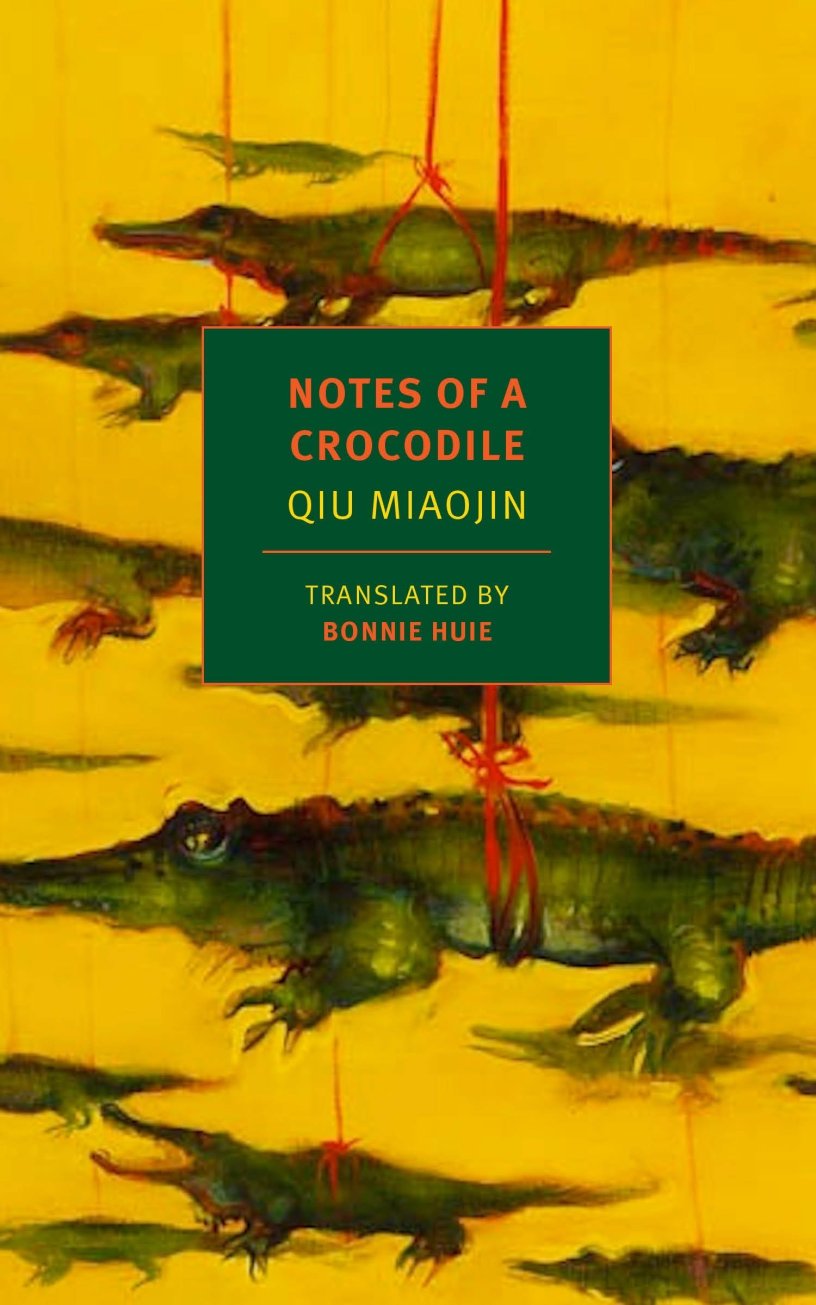

Notes of a Crocodile, by Qiu Miaojin

Translated by Bonnie Huie

(1994, translated 2017)

NYRB Classics

(Modernist Coming of Age Story)

Qiu Miaojin achieved fame as an avant garde writer, film-maker, and LGBTQ martyr. Taiwanese, she graduated from an all girls secondary school and graduated from Taiwan University. In 1994 she moved to Paris, where she pursued a degree in Clinical Psychology and studied Feminism under Helene Cixous. Notes of a Crocodile, her most popular work, was written in response to a series of sensationalist media reports on lesbians in Taiwan. It seems there was a short and intense craze for information about all things lesbian, resulting in newscasters psychologizing the illegal lifestyle, exoticization, and portraying lesbians as an anthropologist might study a hidden tribe. Qiu casts herself as a “crocodile” that wears a human suit. Throughout the novel, she features a variety of talking heads, politicians, physicians and police reporting on the crocodilian race. The narrative she presents is difficult to follow — non-linear and recursive. The narrator describes her struggles to come to grips with her sexual identity from the final years of her secondary education through her college experience. The central relationship she describes is profoundly obsessive and self-destructive, as the narrator, Lazi (a play on the Taiwanese slang word for lesbian), falls for the icy Shui Ling. Their physical passion is brief; their break-up seems to occur early, yet Lazi continues to perseverate over the loss of her beloved, writing to her, stalking her, inventing melodramatic conflicts and reunions with her idol, to whom she gives power over her life and death. Shui Ling herself seems to take pleasure in the torment Lazi endures, dropping a suggestive line out of the blue or showing up unannounced at Lazi’s graduation. Eventually, Lazi finds a new love, Xiao Fan, a beautiful woman five years her senior who has been engaged to a man for ten years. Lazi places herself in thrall to another unavailable woman. Qiu bares her heart with abandon and sometimes overwhelming self-indulgence. She is more successful as a storyteller when describing the highs and lows of her male homosexual friends and her bisexual on-again, off-again sex partner. These characters are larger than life and she portrays them brilliantly; her distance from them prevents her from drowning their stories in her own self-loathing. The book is touted as a cult classic of queer literature, but it is decidedly not an upbeat read. Qiu’s other major work is Last Words from Montmartre, a series of twenty letters that, according to the author, can be read in any order. Some of the letters are suicide notes, and sadly, the novel was published after her death by suicide in 1995.

“One day it dawned on me as if I were writing my own name for the first time: Cruelty and mercy are one and the same. Existence in this world relegates good and evil to the exact same status. Cruelty and evil are only natural, and together they are endowed with half the power and half the utility in this world. It seems I’m going to have to learn to be crueler if I’m to become the master of my own fate. Wielding the ax of cruelty against life, against myself, against others. It’s the rule of animal instinct, ethics, aesthetics, metaphysics—and the axis of all four. And the comma that punctuated being twenty-two.” (7)