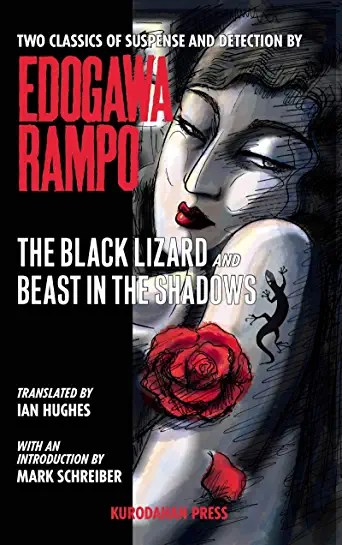

The Black Lizard and Beast in the Shadows, by Rampo Edogawa

Translated by Ian Hughes

(1934, translated 2006)

Korudahan Press

(Crime/Detective Novel)

This pairing of texts is quite interesting. Rampo was strongly influenced by Arthur Conan Doyle, Edgar Allen Poe, and Maurice LeBlanc. Edogawas’ master detective was Kogoro Akechi, whom he first introduced as a member of a Young Adult literature series about a group of boy detectives. In The Black Lizard, Kogoro is an adult and he’s been hired by a powerful jeweler who fears his daughter will be kidnapped. Edogawa also introduces an iconic femme fatale, a woman known as “The Black Lizard,” named for the scandalous black lizard tattooed on her upper arm. In addition to the taboo body modification, the villainess is a master thief and an exhibitionist; the story begins with her writhing naked in a criminals-only bacchanal. The story is not especially brilliant and the characterization is almost comically wooden. Like LeBlanc’s The Hollow Needle, the tale is a series of elaborate chases and escapes facilitated by increasingly elaborate disguises and “locked room” puzzles. Edogawa championed “ero, guru, nansensu” in (eroticism, grotesquerie, and the nonsensical) in his writing, and The Black Lizard provides all that in spades. The villainess’s greed and lust are combined, her desire to possess beautiful gems as well as beautiful people, a secret revealed in the climax of the novel, is more than grotesque. At the same time, as perverse as the Black Lizard is, the story itself seems predictable and naive. Edogawa seems to be mucking about and trying very hard to titillate and scandalize his audience. Beast in the Shadows is an entirely more sophisticated piece. The narrator is an author of crime novels. He meets a married woman who is a fan of his work, and sometime later, the woman contacts him to share a terrible secret: she has been receiving blackmail letters and death threats from a stalker who has access to the most intimate details of her life. She suspects that the author of her torment is a lover she rejected in her youth. The narrator promises to help the wife, and in the process, they begin to realize that the spurned lover may also be a crime novelist–a rival of the author whose stock in trade is gratuitous violence, sex, and gore. One of the thrills of reading Edogawa is the intertextuality and self-reflexive nature of his work. For example, in The Black Lizard, the fictional Kogoro solves puzzles by realizing the criminal must have read a short story, “The Human Chair,” by a famous crime writer. Edogawa’s detective doesn’t actually name the author, but we delight in his cheek: the author of “The Human Chair” iss Edogawa himself! Edogawa takes this technique to the next level in Beast in the Shadows, as the well-meaning detective discovers that the criminal is using techniques taken from the work of his rival-and which are also short stories (“Games in the Attic,” “Murder on ‘B’ Hill”) written by Rampo! Tellingly, the narrator discovers the truth by drawing on another tale of the villain’s, “One Person, Two Roles,” also a tale published by Edogawa. Finally, the true name of the villain seems to be none other than a slightly modified version of Edogawa’s real name! Beast in the Shadows is not only a tour de force of deduction but also a brilliant study of the interaction between the reader, the book, and the audience on a par with Borges and Calvino. One final reason to put Beast in the Shadows on your reading list: Edogawa also confesses his fascination with voyeurism and mirrors and lenses, first at a freak show and in the scene below.

“Just like the character in ‘Games in the Attic,’ I peeked down into the room below and it seemed entirely possible that Shundei had gazed in ecstasy there. The strange scene in the ‘netherworld’ visible through the cracks between the boards was truly beyond imagination. In particular, when I looked at Shizuko, who happened to be right below me, I was surprised at how strange a person can appear depending on the angle of vision.” (209)