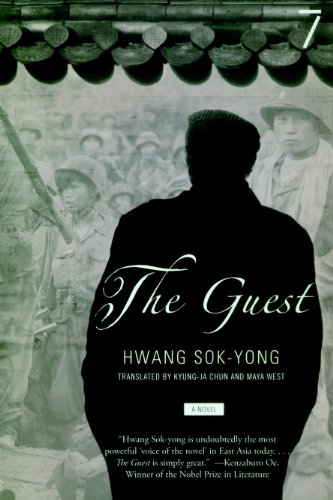

The Guest, by Hwang Sok-yong

Translated by Chun Kyung-Cha and Maya West

(2001, trans. 2006)

Seven Stories Press

(Historical Novel)

The Guest is a controversial historical novel about The Sinchon Massacre, which resulted in the deaths of some 35,000 people. The fifty-four-day event, which took place in Hwanghae Province in North Korea between October 17 and December 7 of 1950, has long been attributed by both South and North Koreans as the work of the American Armed forces. To commemorate the slaughter, North Korea built a museum and memorial to the victims. Beginning in 1953, Kim Il-sung, Kim Jong-il and Kim Jong-un all made important symbolic visits to The Sinchon Museum of American War Atrocities. There, it is possible to see photographs, piles of shoes belonging to the dead, and art inspired by the tragedy. Visitors tour the underground bunker where hundreds of civilians were burned alive, meet survivors who recount the horrors they experienced, and have the opportunity to honor the martyrs. But Hwang Sok-yong tells a different story, one supported by The Korean Institute for Historical Studies. In Hwang’s novel, American troops and a small unit of South Korean scouts do pass through the area at that time but pass on: their objective is to reach Pyongyang. Hwang sets the blame for the massacre at the feet of his fellow Koreans, claiming that factions of pro-communist and anti-communist villagers largely made up of Christians exploded into almost tribal violence, bathing themselves in the blood of a brutal internecine conflict. Interestingly, Hwang-Sok-yong titles his novel The Guest, which is the name Koreans gave to the European disease of smallpox. As an invited or uninvited guest, the foreign disease laid waste to the Korean population. Using this metaphor of a foreign infectious disease, Hwang makes the case that European Christianity, Chinese Communism, and Japanese Imperialism–three outside ideologies–infected, maddened, and possesed Koreans, creating extraordinary pressures and resulting in pandemonium. Hwang breaks the flow of his novel at different junctions to give an exhaustive history of Christianity in Korea. He does not demonize the religion, but he does help clarify the conflicts between the pro-communists, the religious community, and the Japanese sympathizers. A third of the way through the novel, characters start to express a belief that there will be a conflict between the God of Europe and the Gods of Chosun–Chosun being the North Korean name for Korea. Hwang calls attention to the ways young Korean Christians expressed the passion for their faith by digging up indigenous religious artifacts and throwing them in streams or by setting up churches on former sacred sites. Even Hwang’s protagonist, the Reverend Ryu of New Jersey, shows signs of adhering to the old animistic rites, and Hwang makes clear in his introduction that his entire novel is structured around a traditional Korean exorcism. The novel is dense and harrowing. In the chapter “Requiem,” a room full of the dead retells their stories so that the spirit of Reverend Ryu’s deceased brother will find peace. Their testimonies are horrifying, but Hwang has them speak their truths without any regard for chronological order, complicating an already hard-to-follow and chaotic series of events.

“He thought he remembered hearing that the power was cut off in the countryside after midnight to conserve electricity. He decided to give up on the light. Feeling around on the table for the water bottle, he found it and took several deep gulps. He was sitting down on the sofa, intending to stay for just a moment, when two men materialized out of nowhere and sat down as well, facing him. It didn’t even surprise him anymore. One was Yohan, elderly with his white hair, and the other was the same middle-aged Uncle Sunnam.” (109)