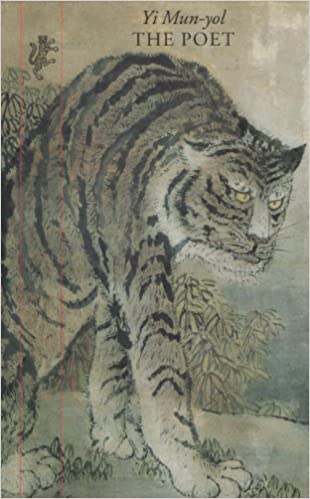

The Poet, By Yi Mun-yol

Translated by Chung Chong-wha and Brother Anthony of Taize

(1992, translated 1995)

Harper Collins

(Historical Novel)

Yi Mun-yol very self-consciously chooses to tell a fictionalized account of a major classical Korean poet about whom very little is known. His subject is Kim Pyong-yon, who lived from 1807 to 1863. He comes from a good family, enjoys high status and has the potential to rise as a scholar, but when his grandfather is perceived to have betrayed his lord in a time of war, the old man is humiliated and executed. The law extends the grandfather’s guilt to his descendant: three generations of his family are condemned to death. Kim Pyong-yon’s father sends his wife and son packing, disguising them as peasants and instructing them to find shelter with former servants. The father then flees for his life. As the boy matures, he gains fame as a wandering poet, a monk-like isolate that is known for the large flat conical hat he always wears to conceal his face. Eventually, the part stands for the whole: Kim Pyong-yon becomes “Kim Sakkat,” Kim of the conical hat. Having grown up in the shadow of his grandfather’s crime, he blames his ancestor for his family’s outlaw existence and perpetual poverty. No surprise then when he wins a great prize in a poetry contest while citing his grandfather’s crime in a poem in praise of the warlord who ordered his death. By this time the warlord had withdrawn the death penalty and Kim Sakkat’s father had returned, yet Kim’s loathing of his grandfather persisted. Yi portrays the lonely life of Kim as he wanders from place to place until one day he meets a servant of his grandfather who tells Kim a story that causes him to rethink everything he believed. According to the servant, the grandfather was a man of true nobility who made a tactical surrender to save the lives of his people and who never stopped working behind the scenes to sabotage the enemy. This alternate history undoes Kim Sakkat and causes him to withdraw even further from society. Now, he deeply regrets writing the poem that established him as a poet and spends the remainder of his short life trying to fathom the nature of truth. Kim Sakkat’s story is, in many ways, Yi Mun-yol’s: Yi’s father went to the Worker’s Paradise of North Korea in 1951. Like Kim Sakkat, Yi sought to restore the legitimacy of his family by denouncing his father in writing–using his art to sever the filial relationship. In writing The Poet, Yi Mun-yol seems to acknowledge that he regrets this act and lives beneath the shame of this betrayal.

“The ideology of the system, long inculcated through various pedagogical methods, together with the examples of fearful punishment frequently meted out on traitors, had raised people’s responses to an almost instinctive level. Not only the classes who shared in the structures and advantages of society, but even those who were the victims of those structures, had been conditioned to shudder instinctively at the very word “traitor” and to consider treason as some kind of deadly disease that could be caught merely by being caught in the proximity of the descendants of such a person.” (35)