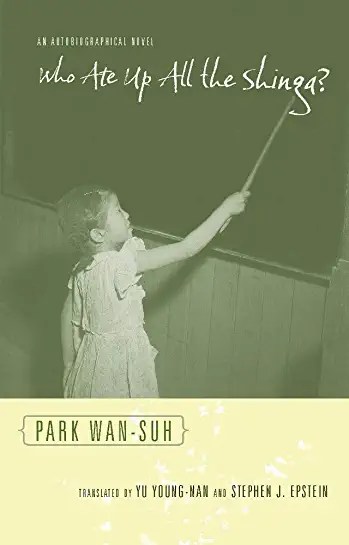

Who Ate Up All the Shinga?, By Park Wan-suh

Translated by Yu Young-nan and Stephen J. Epstein

(1992, translated 2009)

Biographical Novel

Park presents this as neither a memoir nor an autobiography. She admits that relatives and friends recall events differently, yet she feels confident that even if she is misremembering details, the story she tells is consistent with the stories she told throughout her life in order to make sense of a difficult and turbulent world. Before beginning, I feel it is important to say that if you ask a person from Korea about this text they will either recognize it immediately as a product of everybody’s “favorite next-door auntie” or screw up their eyes in confusion, as they grapple with the word shinga. Context suggests it is edible, but the word, which is apparently linked to a certain type of wild grass, persists only in the local dialect of a particular farming region in Korea. Park and her friends, who always seemed to be at risk of starving, delighted in discovering this sweet grass that tasted to them like candy. Park was born in 1931 and grew up on farmland near Kaesong. She went to kindergarten and grade school learning Japanese from teachers installed during the Japanese occupation. She witnesses the degree to which her family and others managed life under the colonizers. She also witnesses the withdrawal of the Japanese and the terrifying rumors that they would kill all the Koreans as they retreated. The family moves to Seoul but flees back to Kaesong in 1945. There immediately south of the 38th parallel, she talks of regular interaction with Russian and US soldiers and a border that existed in name only. She also observes the ongoing battles between Koreans, political and regional tensions that had been simmering just below the surface of colonial rule. When, in 1953 the North Korean Army sweeps through and captures Seoul, Park records the flight of young men into the mountains to hide from being conscripted to fight for the communists. Each time Seoul falls (it is taken four times–once by the Chinese) Park’s way of living is put in grave peril. There are family meetings to discuss strategy, relatives are hidden or spirited away and friends and acquaintances perish. Throughout, the relationship that comes under the greatest sympathy is the one between Park and her mother. They are often at odds and Park at times sounds resentful. She had always preferred country life to the chaos and squalor of Seoul and longed to return to Kaesong. What she could not know is that her mother yearned to go to Seoul in order to escape the rigid, limited life she would have had to live as a country woman. In Seoul, she imagined, she could reinvent herself as a modern woman.

“A few days later, the political situation flipped upside down again. The ROK Army and United Nations forces gained control of Seoul. For three months, young men seemed to have vanished, but now they spilled out onto the street from wherever it was that they’d hidden themselves so resourcefully. They hugged each other, their hair long and their faces as white as a sheet of paper. Embracing the triumphantly returning ROK Army, they cheered madly and danced. These young men could hardly have survived in hiding so long merely through sheer endurance and the protection of their families. We alone had been the fools. (230)