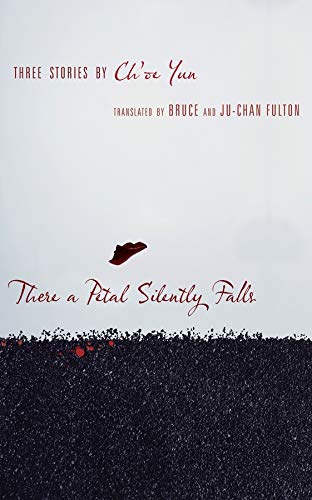

There a Petal Silently Falls, by Yun Ch’oe

Translated by Bruce and Ju-Chan Fulton

(1983, translated 2006)

Columbia University Press

(Novella and Two Short Stories)

“There a Petal Silently Falls”

Miss Yun’s first story takes place in the immediate aftermath of the Gwangju Massacre. In May of 1980, President Chun Doo-Hwan sent in the army to violently suppress a popular uprising of workers and students who were seeking better pay, safer conditions, and an end to martial law. There has never been an official accounting of casualties, though there is strong evidence that at least two thousand civilians were beaten to death or shot. Yun exploits the confusion, trauma, and shock of the event to full effect, telling the story primarily through the eyes of a fourteen-year-old girl who followed her mother to the labor strike and witnessed her mother’s death. Carried along by the fleeing crowd, the girl enters a fugue state and begins wandering throughout the region searching for her brother’s grave, an obsession that we can study further in Kang Han’s Human Acts. Traveling alone in tatters and living in the margins between village and forest, she is victimized by countless men. One construction worker rapes her and is then overwhelmed by guilt, hiding the girl, feeding her, but unable to resist his desire to violate her. Critics suggest Yun’s shell-shocked orphan is a symbol of Korea itself, defenseless and perennially victimized by imperialists and so-called allies. The clearest, most comprehensible moments in this nightmare are provided by the schoolmates of the victim’s dead brother. Unable to do anything to protect him, they have determined that they can only make up their debt to him by finding his missing sister. On July 20th of 2008, writing of the publication of the English translation of “There a Petal Silently Falls, “ Daniel Jeffreys of the South China Morning Post wrote, “Yun’s account of post-traumatic disorder is an unforgettable reminder of the price paid by those who survive state-sponsored brutality.” The passage below describes when government agents reported that her brother, who had been arrested two weeks ago, had died in custody.

“Mother turned strange and didn’t realize it. People said her soul had left her. I wasn’t sure what they meant by that. I had a notion that a bizarre spirit was living inside her. She walked much faster than she ever had before, mouth clamped shut, eyes dry, a red flush to her tanned cheeks, head erect, eyes gazing off into the distance….What was really strange was that she wanted to dictate letters to me, letters whose contents I didn’t understand, and she asked me, the stutterer, to read things written down on paper. By that time I wouldn’t have been surprised if she had somehow learned to write overnight. (33)

“Whisper Yet”

This story shuttles back and forth in time; as in many stories from the 1980s, the past begins with the Korean War and the Partition. A young family is on an affordable vacation: housesitting at a friend’s orchard. The wife’s loving husband spends his days fishing at a nearby lake while she and her preadolescent daughter explore the house, orchard, and small pond. The setting sparks nostalgia for the woman. Watching her child play at the pond and climb in the trees, she remembers when she whispered to her when she was in the womb, wondering aloud what her life would be like and telling her memories of her own childhood. Even the child’s name, Un-ha, relates to the mother’s memories of youth: it means lake. Always she spoke of life with her parents and their struggle on another orchard and lake that have long ago been sold and leveled for construction. These were poorer, more desperate times. Her parents were forever preoccupied with their labors and her father’s illness but everything changed when her father hired a handyman to work on the farm. He was a little older than her father and over time she came to think of him as an uncle. She enjoyed watching him at work and she was captivated by the way he talked to her. She was sure he was a poet. When she thought of her time as a child, she always thought of her time spent with Ajaebi. She would even watch and try to listen as her parents and Ajaebi talked, always, it seemed to her, in whispers. As it turns out, the woman’s father and handyman’s relationship was more complex than she could have then imagined, as Ajaebi was not simply a jack-of-all-trades but a government official who tried to flee to the North, failed and was now living incognito, far from his hometown and his wife and children. And as the woman’s parents had come to the orchard from Songnim in Hwangwae Province, Ajaebi had ironically found shelter with North Koreans who had fled south. These last details are only some of the circular relationships and symbols in this quiet, reflective short story. Please note that the translators use the McCune-Reischauer Romanization method–this will explain why the Korean names look somewhat different in this publication.

“We had ourselves a delightful time playing in the water and acting silly. We returned dripping wet to our mat in the shade and she sat quietly, chin on her knees and wearing the prettiest expression. When she was little she sometimes awakened before we did, and looking up toward the window she would quietly regard the dawn light streaming in. Her face as I awoke to discover it then was the face of a philosopher.” (165)

“The Thirteen Scent Flower”

Of the three short stories in the collection, “The Thirteen Scent Flower” is the most “modern” and experimental. Yun creates something of a mash-up of genres. There is a bit of coming-of age, romance, magic-realism, and folklore elements, as well as a satirical study of modern Korea’s obsession with capitalism-at-any-cost, the solipsism of scientific researchers, and not surprisingly, the vanity of writers. At the core, there is a romance between a young man and woman. The man, Bye, inherited a map, a compass, some half-baked inventions, and a one-eyed truck from his deceased uncle, The girl, Green Hands, is a stranger in the city. She works for florists here and there, gets sacked for cutting bonsai from their wire armatures, and when we first meet her, she is on a dark stretch of road preparing to throw herself in front of a speeding vehicle. Instead, the two meet and drive to the ancestral home of the girl in order to visit her grandmother. Before dying, the grandmother gives Green Hands a handful of seeds and orders her to plant them when she is dead. Though the land is frozen and they are in deep winter, the flowers grow and thrive in the snow and wind. Taken by the beauty and the fragrance of the flowers, the couple propagates the plants. As word grows of their accomplishment, visitors flock to the moribund village, revitalizing its economy. Soon, representatives from pharmaceutical companies descend on the village to capitalize on the possible healing compounds of the plants and various botanists begin engaging in discrete research, each hoping to gain fame through publishing their findings first. There is also a man who discovers that the scent of the flower cures his low-altitude sickness (a disease that only he and one other person suffers), a rare plant specialist with the initials KGB, so much attention to numbers that one begins to suspect that there is a numerological subtext to the story, and an ending that directly references the conclusion of the opera Tristan and Isolde.

“Having buried Grandmother and readied themselves for winter, Bye and Green Hands were able to sleep soundly for the first time since they had met. Putting out of their minds their loneliness, their hunger, the cold, and their unease. So short were the days this deep and high in the mountain they sometimes awoke to surroundings gloomy as night, and went right back to sleep. And there were times when they were afraid to open their eyes and slept on instead. One winter day, when they had awakened from one such lengthy night of sleep, they saw behind the house five flowers the color of light maroon. A plant that seemed to have forgotten the season in which it was supposed to bloom.” (141)