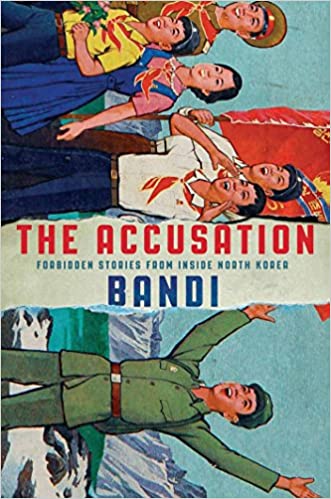

The Accusation: Forbidden Stories from Inside North Korea, by Bandi

Translated by Deborah Smith

(trans. 2018)

Grove Press

(Short Story Collection)

We know very little about the author of these stories. It is believed they were written between 1989 and 2005, likely composed by a member of the North Korean Writers’ Guild. The stories were smuggled out of North Korea and the writer’s name is unknown. He or she goes by the pseudonym “Bandi,” which means “firefly.

“Record of a Defection” (1989)

As one might expect in a collection smuggled out of “The Hermit Kingdom,” “The Accusation” originates with the discovery of a secret effort to undermine an elemental order. However, the arena of inquisition is domestic, not political, though the righteous vehemence of the investigation clearly runs on rails laid down by generations of oafish, monomaniacal, and merciless secret police. The crime: an insecure man discovers that his wife is taking birth control pills. In a strong collection, this story stands out as a tour de force of narrative skill and eye-opening invention.

“If it was true that she feared mingling her bloodline with that of a “crow,” feared seeing her children tarred with the brush of a Party traitor, the generous affection she’d always shown me would have been nothing but a mask, and that simply wasn’t something I was prepared to believe. If I even dared to doubt that woman, I felt, I’d deserve to be struck down. My only wish was for everything to be revealed as a misunderstanding, and for my wife to remain as she had always been, a generous and loving companion.” (10)

“City of Specters” (1993)

The specters in this story are everywhere. They are of extraordinary, superhuman scale, so tall that they can peer in the windows of multi-story Pyongyang apartments. They are the giant likenesses of Kim Il-sung and Karl Marx, and they appeared as part of the preparation for celebrating National Day. Gyeong Hee should be happy to live in Kim Il-sung Square and to have a front-row seat to the celebration. Her status is high: her father died fighting, a martyr to the cause, and her husband is the son of a supervisor in the propaganda department. True, she considers her husband somewhat spineless, but their future looks assured until their two-year-old son develops a new habit: he screams in inconsolable terror when he sees the image of The Great Leader.

“Wasn’t I telling you only yesterday about the ‘Rabbit with Three Burrows’? Like the rabbit who keeps three burrows to hurry into as needed, you can never be too careful. That’s the moral of the story. Always stamp on a stone bridge before crossing, to check that it will bear your weight. Those are the rules for living in Pyongyang.” (48)

“Life of a Swift Steed” (1993)

A conflict with an electrician on a cold winter’s day causes the police’s chief of investigations to call factory supervisor Yeong-il, about the conduct of one of his workers, Seol Yong-su. The matter is of great significance: the previous day, Seol Yong-su brandished an ax at a man sent to free a telephone line that had been caught up in the branches of a tree in his courtyard. Could Yeong-il speak to the man’s character? Could he get to the root of the problem and persuade Seol Yong-su to allow the workers access to the tree? The call is troubling. Yeong-il and Yong-su have known each other since fighting side by side to drive the Japanese out of Korea. They were present at the birth of the Communist Party and have lived and worked together ever since. They had pledged body and soul to the Party and look forward to the promised rewards of their long labor. What will come of investigating his old friend? And why did his friend threaten a man with an axe?

“Only then did he notice what Yong-su had spread out over his lap: a jacket weighed down with dazzling medals. Perhaps he’d been choosing a place to pin the latest addition, the one he’d received today, and had lost himself in reminiscence. But whatever old memories might have been revived, the freezing room and Yong-su’s dark expression hinted that the joy they gave him was not unadulterated.” (73)

“So Near, Yet So Far” (1993)

“So Near, Yet So Far” introduces us to both a “Class One Event” and “Department Two.” Myeung-chol wishes to be a filial son, but he hasn’t seen his mother in years. First he was in the army, but after he was demobbed his division was sent off to work for the Great Leader in the mines. He married and had a son, and he tried to get special traveling papers to visit his mother by making up a lie: his mother was deathly ill. All of his attempts to journey to the village he was born in come to naught, foiled by bureaucratic intransigence. When word arrives that his mother is actually dying, Myeung-chol faces the most insurmountable obstacle of all. The village is hosting a “Class One Event,” which means it is on the route of Kim Il-sung; in the weeks leading up to the Great Leader’s passage, all non-essential travel is cut off and it is impossible for Myeung-chol to secure traveling papers from Department Two. To what indignities will this good son submit himself in order to see her one last time before she dies?

“As he stumbled out of Department Two, his legs barely able to hold him up, a wave of soundless sobs threatened to choke Myeong-chol. His eyes, which shone with the gentle innocence of a calf’s, brimmed with bitter tears. Was Solmoe, the village he’d grown up in, some foreign city like Tokyo or Istanbul? How could his own village, in his own country, his own land, be so remote, so utterly unreachable?” (97)

“Pandemonium” (1995)

The narrative of “Pandemonium” consists of a series of jarring flashbacks. One of the moments of “pandemonium” occurs when Mrs. Oh and her husband travel to the village of their daughter who is due to have her second child. The proud couple travel by train with their five-year-old granddaughter, Yeung-sun, whom they have been taking care of in the last months of her mother’s pregnancy. The homegoing is a delight for the little girl, but just as the train arrives at the station a riot breaks out over the distribution of bread. Mrs. Oh manages to tuck a few precious loaves under her as she is trampled to the ground. Her husband suffers a break in his pelvis and her granddaughter’s leg is broken. When the two are taken to the hospital, Mrs. Oh attempts to continue on foot to attend her daughter’s delivery. Unfortunately, a “Class One Event” almost prevents her from attending the birth of her second child or delivering the health-giving gallbladder of a wild boar.

“Of course, these words of discontent could never pass their lips. The Class One event taking place just then involved Kim Il-sung traveling along that same railroad—Kim Il-sung, whose sacred inviolability meant that even if he announced that a convicted murderer was to be allowed to live, anyone who dared so much as hint at disapproval would be sealing his or her own fate, with no more recourse to reverse it than a mouse faced with a cat.” (126)

“On Stage” (1995)

The Great Leader, Kim il-sung, died three weeks ago, yet every citizen still passionately mourns and each funerary altar is still covered in heaps of fresh flowers. Everyone is dutifully performing any and all rituals to demonstrate their loyalty. However, in the Ministry of State Security, there is cause for concern. The son of one of their own bowibu family, Hong Yeong-pyo of the Union of Enterprises, was seen holding hands with a girl of a “black background:” her father is a political prisoner. Worse, the couple was found with alcoholic spirits as they pretended to search the mountains for more flowers for the extended funerary rites. The discovery was not unexpected, but his son’s conduct could be a disaster for the entire family. His son was an actor in a government troupe that put on politically correct versions of traditional dramas as well as state propaganda. He had gotten into trouble before: when he and his team were punished for failing to act with sufficient levels of “stage truth,” he caused a sensation by composing two comic pieces on the spot. When would he learn what he could and could not do?

“To those gathered in the room, the announcers’ voices seem unusually deep and clear, and they fancy that they see tears streaking down from the ceiling. The sound of the rain, the sound of the wind . . . Looking out beyond the window, its glass blurred by a solid stream of rainwater, they see the trailing tendrils of a gnarled old willow whipping through the air like a nest of snakes.” (151)

“The Red Mushroom” (1993)

Yunmo is a journalist in North Korea, which means he must write stories that glorify North Korean socialism. In many cases, he must simply lie, as in the present instance: floods have washed away precious soil, crops are failing and yields are down, yet he must compose an article about a miraculous rise in the production of bean paste. Though he drinks, partly to shake off the sting of his nickname–”Mr. Bullshit Writer”–partly to numb his thwarted desire, he still yearns to write a meaningful story, so he sets out to learn more about Ko Inshik. Ko was from a well-to-do family. He earned a degree in “food crop engineering” and had a promising career in light engineering. Unfortunately, his brother, who was assumed to have died in the war, surfaced in South Korea. As a consequence, Ko Inshik is sacked from his office and forced to reclaim land from the jungle on the side of a mountain. Can Ko possibly turn the mountain farm into a productive asset and redeem himself in the eyes of the state?

“It had been close to three months since the town’s production of soybean paste had slumped from sporadic to nonexistent, yet Yunmo was now expected to write an article on the factory’s return to normal operation—like reporting on the news of a birth before conception had even occurred!” (183)

Every single one of the short stories in this collection showed the constant fear and mistrust that citizens living under a dictatorship have to endure just to survive and how it permeates all relationships, not just with those in authority but husband and wife, parent child, even past generations. Even total obedience is not a guarantee of safety. If this collection of stories reads as dystopian fiction, the reader should consider themselves lucky as they have never lived under a totalitarian regime.

LikeLiked by 1 person