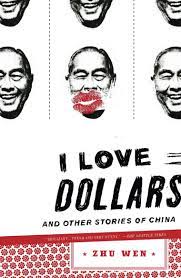

I Love Dollars and Other Stories of China, by Zhu Wen

Translated by Julia Lovell

(1994-1999, Translated 2007)

Weatherhead Books on Asia

(Short Story Collection)

“I Love Dollars”

Bawdy, raucous, and crude, “I Love Dollars” is the motivational mantra of the brash, narcissistic narrator. The inciting incident is a surprise visit by the narrator’s father; he catches his eldest son in flagrante delicto with Wang Qing, an older divorced woman who tolerates the sex-mad and faithless narrator. As she makes an awkward exit, the father explains that he has come to town in the hopes of having a face-to-face meeting with his youngest son, who seems to have stopped attending his college classes in order to pursue a career as a rock musician. The father is genuinely concerned; baffled that his second son is throwing away an education in Mathematical Statistics, he wants to confront the boy and steer him on the right path. The narrator, a sex addict who moderates his perverse obsessions by free-lance writing, understands the night’s mission. What follows should be a tale of Confucian family piety and a return from chaos to order. But this is China in the 1990s. Confucianism has been crushed, the Tiananmen Massacre has made clear that the people will be denied justice, and Deng Xiaoping has whipped up the Chinese to pursue capitalism by any means necessary. The only fragment of Confucianism that the narrator retains is a conviction that he must get his father food, drink, and women–coincidentally, what the narrator desires. So begins a night-time odyssey in bars and brothels, a comical quest that leaves the poor father utterly flummoxed by the behavior of the children he has raised.

That woman back there, he said to me, totally serious, as we left, the one with no breasts, she really wasn’t a prostitute. How can you be so sure? I said. She was a bit like Xiao Qing, he said. She was still a child. So what if she’s like Xiao Qing? Don’t you think your daughter could turn herself into a pretty passable prostitute? Oldest profession in the world—older than any of our traditions. If my beautiful little sister stepped outside the school gates and onto the streets, as long as she enjoyed her work, I wouldn’t mind at all. (8)

“A Hospital Night”

Zhu once again presents us with a Confucian dilemma. The narrator comfortably enjoys the benefits of an on-again, off-again sexual relationship with Li Ping. He might care for her, he might not: love is an emotion that has never truly visited. Then, disaster. Li Ping calls: her father is in the hospital. The whole family has gathered at his bedside. Will the narrator come? Initially, he balks. He has thus far avoided meeting the family and he suspects she is using the occasion of her father’s emergency surgery to force a formal introduction. After much deliberation, he decides to go. Once there, he discovers that the family is trying to work out a schedule to provide care for the father overnight. Someone will need to stay in the room to help the old man urinate and make sure that the nurses provide him with a saline drip when needed. This is a job that can only be done by a man, and so the narrator ends up spending a hilariously resentful and awkward night providing intimate care for Li Ping’s father, who hates him and fights him at every opportunity. The narrator must also contend with the two other patients in the room, their family attendees, and a sexually frustrated nurse who wants to have her way with him. The situation is both slapstick and Chekovian: by morning, a blessed peace settles over the room and the narrator seems to have become a changed man.

Looking for a straw in the cupboard at the foot of the bed, I found only a soup spoon, so decided to use it to feed him mouthful by mouthful. I should have expected the unexpected, though: as I reached for the spoon, he spotted his opportunity and sprang a surprise attack on the mug, like a wounded orangutan. Though he didn’t win his prize, he did succeed in spilling the water. His left claw now soaking wet, his eyes remained anxiously pinned on the progress of the mug in my hand. Now was that really necessary? I asked. The failure of his punitive raid—on top of the inevitable pain from his scar—now shamed Li into rage: Give me the water now! he wheezed, beard standing up like hedgehog spines. (71)

“A Boat Crossing”

This is one of the most mysterious and elegant stories in the collection. Again, there is something vaguely Chekovian in the situation, and the setting, riding at night on a passenger boat up the Yangtze is reminiscent of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness or Melville’s The Confidence Man. The narrator is an enigma. As he waits at Cape Steadfast for the delayed vessel, he is impatient to shed the two acquaintances who wish to send him off and wary of a mysterious woman in black he wishes to avoid. Once on board, he finds himself in a third-class berth with three savage-looking men who are led by a man the narrator refers to only as “the ghoul.” Later, the woman in black enters, followed by an awkward country girl in her teens. The child has been made out to look like an adult. The woman wants to continue relations with the narrator; apparently, they have a history. A waiter arrives with baijou, a drink containing 55% alcohol. The tiny berth becomes even more chaotic and the narrator flees. Confronted by an officious ticketmaster, he arranges to switch to a second classroom that he will share with a traveling battery salesman. A new drama will unfold there. Truly what happens aboard the ship (called the Orient) by the way, is nightmarish and completely unforgettable in every way. As in “A Hospital Room,” the narrator reveals himself as a selfish and cowardly man who becomes a touch more human by morning, arriving at a place where he feels confident enough to confess his true identity to his interlocutor.

The woman in the black jacket was about thirty, or maybe a bit older, I couldn’t say exactly. If you’d asked her directly, you’d have gotten even less precision. On her lower half she had on a less than dignified pair of pinkish slacks. She’d told me her name was Li Yan, a false name I reckoned, but one that I had no thought of challenging. But she knew my name, my real name, which made me feel like I was at a disadvantage. Where are you headed? Li Yan asked me. Wan County, I said. Again, I was telling the truth, but not because I wanted to—I just hadn’t had time to invent a lie. (107)

“Wheels”

“Wheels” seems to be a study of modernity, corruption, and fate. The narrator proposes a compelling theory: mankind’s “evolutionary” discovery and use of the wheel is our greatest disaster as it has only increased the speed at which we hasten toward our own ruin. He is an impoverished boiler mechanic (this was the author’s profession prior to his writing career) who lives in a shed and commutes to work on a ten-year-old bicycle. One day he is confronted by a triad enforcer who takes possession of his bike and then introduces him to a frail old man, purportedly the enforcer’s father. The old man and his son insist that the day before, the narrator, while passing by on his bike, struck the left shoulder of the old man, gravely injuring him. They demand reparations. The narrator protests. He never struck anyone, the old man is faking it, he has but a few hundred yuan to his name, and he needs his bicycle to work. After much discussion, the enforcer takes the bike and everything in his pockets. The next day the narrator takes a little over 807 yuan in savings to purchase a new bike, but once again he is accosted by the enforcer, who robs him of his life’s savings. When the narrator begs for his money, the enforcer assures him that they are taking the old man to the hospital to be examined and that they will only use as much of the money needed to pay for the doctor and medicine. They return a few hours presenting him with receipts for 807 yuan. Once again, we are in a world where no one can be trusted and there is no recourse for the victims of crime. There is no social contract at all, so it is not surprising that, even when his life is threatened, the boiler mechanic knows better than to call the police.

The factory where I worked was in an industrial area—segregated from Nanjing proper by the river—which had started out as a small town renowned only for being the most murderously violent hole in the entire Jiangbei region. More recently, the government had purposely developed it into a satellite zone, where almost all Nanjing’s industry was now concentrated. It must, of course, also have entered into the government’s calculations that a satellite can get hideously polluted without having much effect on the mother planet. A satellite, as it spins merrily around, will trace one massive wheel in space, and wherever there’s a wheel, there’ll be trouble. (153)

“Ah Xiao Xie”

What a wicked little tale! The narrator is, again, a boiler mechanic. He and hundreds of other university graduates are hired to construct a nuclear power plant of Soviet design, a facility that was to be the envy of all of China. However, shortly after some of the components were shipped, Russia collapsed. Rather than abandon the vaunted project, the Chinese government doubled down on its commitment and began to pour more and more money into the plant. Yet because nothing could be completed and there were no experts on hand to guide production, the workers and technicians were held in limbo, forever in training, year after year. At least ten or more years pass and the workers realize that their skills are atrophying and that other plants, constructed with parts from Japan and Switzerland, are on the cutting edge of technology. Xiao Xie, a computer analyst, petitions to be released from the moribund project, but the higher-ups, fearing that he will incite a mutiny, refuse to let him go. Eventually, they agree, but only on the condition that he repays them for his years of training. In addition to Zhu’s criticism of Chinese bureaucracy and graft, he also turns his attention to the insidious impact of bullying and how human self worth is tied to wages.

Almost everyone I knew wanted out: because we were still being trained, because our nonexistent power plant wasn’t generating any profits, and because our salaries had been squashed as low as was humanly possible—most of us were getting several hundred yuan less per month than our contemporaries who’d graduated at exactly the same time but who had jobs elsewhere. For those trying to scrape together the money to get married, our salaries were a serious problem. It was a clash of calculating cultures: the municipal government thought in hundred millions, the factory manager in millions, while we ordinary workers measured our profits and losses in paltry hundreds. (188)

“Pounds, Ounces, Meat”

The shortest story in the collection deals with an ordinary experience: the narrator and his girlfriend stop by the market to purchase half a pound of meat. Once at home, they discover that the meat concealed a large bone. Feeling cheated, they return to the market and demand a better cut. The vendor insists that the cut is fair: he sensed the bone was present and merely subtracted the weight of the bone from the weight of the meat. To prove his point, he cuts out the bone and weighs the meat a second time. Voila!–a half pound of meat. The couple can’t bring themselves to believe what they have seen and challenge the accuracy of the vendor’s scales. More and more citizens are drawn into the dispute as the irate couple seeks out various types of scales. They also battle with their confusion over different types of units of weights. The old merchants mock the college-educated youths who are incapable of making simple conversions in their heads. How does one seek justice in modern China? Are all the scales of justice rigged? Are the older generations wise to accept the patent falsehoods before their eyes as the truth? Zhu also continues his reflection on the way we value one another, invariably seeing characters as dollars or portions of dollars. The theme runs throughout all the stories, but it is best embodied by the narrator’s description of his girlfriend as he pursues her down the street:

I then stepped calmly over his head and strode off in pursuit of my girlfriend. But by the time my lung capacity had abandoned me, my girlfriend was still no bigger than a two-cent coin. As my ultimate ambitions lay in enlarging her into a five-cent piece, I broke into a trot and, after a good deal of pain and effort, finally fulfilled my dream. But the instant I relaxed my efforts even a little, she shrank back to two cents and then, before long, to one. Dispirited, I stopped. This pursuit, it seemed, was not going to be the piece of cake the first one had been. (224)