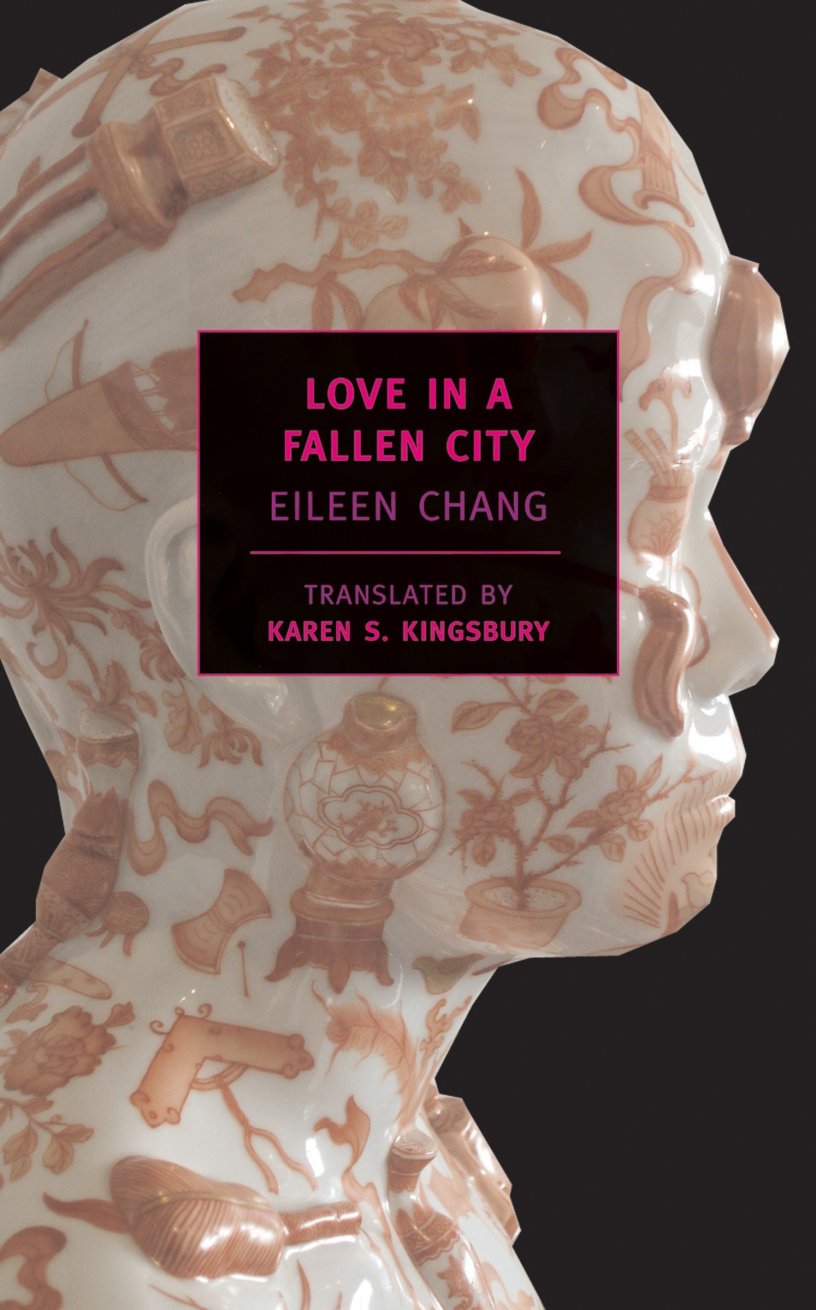

Love in a Fallen City, by Zhang Ailing aka Eileen Chang

Translated by Karen S. Kingsbury and Eileen Chang

(1943, trans. 2007)

NYRB Classics

(Collection of Short Stories and Novellas)

Ms. Zhang Ailing was raised in a high-status family in Shanghai, where she grew up speaking Mandarin and English. She was accepted by the University of London; when World War II broke out, she instead went to the University of Hong Kong, where she studied English Literature. She achieved early success as a writer between 1943 and 1945, and she is often described as one of the great female writers of China’s 20th century. However, her status suffered a fatal blow when she married a man who was later charged with being a Japanese collaborator. Zhang Ailing was suddenly a persona non grata in her home. She fled first to Hong Kong in 1952 and then to the United States in 1955. She lived in California until her death in 1995. Ms. Chang’s early writings were rediscovered in the 1970s and she was once again hailed as one of China’s four female geniuses. She continued to write while in the United States; several novels were published after her death. Love in a Fallen City contains four novellas and two short stories: “Aloeswood Incense: The First Brazier,” “Jasmine Tea,” “Love in a Fallen City,” “The Golden Cangue,” “Sealed Off,” “Red Rose, White Rose.”

“Aloeswood Incense: The First Brazier”

(Novella)

Zhang Ailing introduces us to Ge Weilong. She is in a Chinese junior middle school when we meet her, so she might be sixteen or seventeen years old. Her mind is set on university, but her father must move, and if he does, she will lose a year of progress and Hong Kong University will be out of reach. Defying her father, she throws herself on the mercy of her aunt, Madame Liang. Liang is the black sheep of the family. Years ago, she rejected the marriage her older brothers arranged for her and became a concubine of a wealthy old man. Dying, he left his fortune and his home to Liang. Madame Liang, now perhaps in her fifties, uses her wealth, her home, and her sexuality to attract a steady stream of men to her decadent parties. Liang sees that Weilong is attractive and offers to support her niece and allow her to live under her roof. She outfits the young girl in the latest fashions and before long, Weilong forgets about school and begins to cultivate relationships with single and married men. Though she longs for love, her aunt lectures her on the harsh realities of married life and advises her to use what she has to her advantage. Aiming for a young Christian in her choir, Lu Zhaolin, she discovers that her ideal man is enraptured with her aunt. Crushed, she turns her eyes to a handsome playboy who has neither name nor wealth. The two desire but do not love each other. After much deliberation and fearing that her aunt will cut her off and her family will reject her, Weilong makes a business proposal: she will marry George Qiao but will continue to work for her aunt, seducing wealthy old men for jewelry and other gifts. As dark and provocative as this tale is, the sexual relationships are handled discretely. Weilong’s rendezvous with George Qiao is hinted at by rainfall, and while the adventures of the maids Glint and Glance are bolder, Zhang uses the lightest of touches to bring their activities into the light. The novella is a brilliant study of economic peril, social change, and modern love. Throughout, Zhang makes candid nods to her influences, such a Pu Songling’s Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio and Cao Xueqin’s Dream of the Red Chamber.

When Weilong opened the closet door again, she found herself thinking back to the spring, and how nervous she’d been that first evening when she’d first arrived. She remembered how, after making sure no one could see her, she’d tried on all her new clothes. Since then the three months had passed in a flash; in that brief time she’d done a great deal of dressing up, eating out, and playing around—she’d even made something of a name for herself. Everything the average girl dreams of, she’d done. It was unlikely that all this would come free of charge. From that perspective, the little drama that had just unfolded was inevitable. No doubt this wasn’t the first time Madame Liang had sacrificed a girl in order to please Situ Xie. And Madame Liang would be sure to require other sacrifices from her as well. The only way to refuse would be to leave the house altogether. (52)

“Jasmine Tea”

(Short Story)

This short story is about a painful and unexpected love triangle. Nie Chuanqing is a twenty-year-old young man attending South China University in Hong Kong. He loathes his father and his new mother. His father beats and humiliates and his father’s new wife treats him like an ignorant child. Having inherited wealth, the father and his new wife seem to be dedicated to frittering the estate away one bowl of opium at a time. The attractive and outgoing daughter of a Professor of Chinese Literature, Yan Danzhu, takes an interest in the young man, perhaps because he is so lonely and so beautiful, perhaps because she feels no threat from him, as she believes he is a homosexual. Meanwhile, Chuanqing rages against his deceased mother for rejecting her first lover and settling on his boorish father. He fantasizes about what his life would be like if his mother had married Yan Ziye, who is now his Chinese Literature Professor and the father of Yan Danzhu! First, he imagines how happy his birth mother would be with the gentle and noble Professor Nan, then he pictures himself being born into that family as Yan Danzhu’s older brother, and finally, he sees himself taking the place of lovely Yan Danzhu. He “sups on supposes”… “like lychees,” experiencing happiness in a respectable family where he feels loved. Who is the third member of this love triangle? Perhaps Chuanqing’s birth mother, Bilyuo, perhaps his Professor of Chinese Literature.

“As for Biluo’s life after marriage–Chuanqing couldn’t bear to imagine it. She wasn’t a bird in a cage. A bird in a cage, when the cage is opened, can still fly away. She was a bird embroidered onto a screen—a white bird in clouds of gold stitched onto a screen of melancholy purple satin. The years passed; the bird’s feathers darkened, mildewed, and were eaten by moths, but the bird stayed on the screen even in death.”

“Love in a Fallen City”

(Novella)

Ms. Zhang Ailing’s novella is classic and iconoclastic. The story begins in Shanghai in 1940. Zhang introduces us to failed Sixth Sister, Bao Liusu, whose marriage has shamefully ended in divorce. Returning home, she suffers significant abuse. When she meets Fan Liuyan, who is going off to pursue a business opportunity in Hong Kong, she impulsively decides to leave her home and pursue him. And although Liusu and Fan share an attraction, Liusu has second thoughts. Can she risk marrying again? Instead, she returns home to an even greater scandal. As the tension at home boils over, Fan arrives, asks her to marry him, and they return to Hong Kong. In a different world, Bai Liusu’s experience might be a romantic comedy, but Zhang uses the affair to expose the rigors of the traditional role of daughters at the dawn of a sexual revolution. Zhang complicates the scene further by having the lovers return to Hong Kong. The Battle of Hong Kong takes place in 1941, and though the period of Japanese colonization crushes the spirit of the island and is a point of shame and sorrow for the Chinese, Zhang’s lovers discover new depths to their relationship while under the Japanese, emerging as if reborn. When the novella was first published, both Shanghai and Hong Kong were under Japanese rule. Interestingly, Zhang hardly mentions the battles and privations. Instead, her characters continue to pursue the desires which motivate them.

“Liusu had taken up with Fan Liuyuan—for his money, of course. If she’d landed the money, she wouldn’t have crept back so very quietly; it was clear she hadn’t gotten anything from him. Basically, a woman who was tricked by a man deserved to die, while a woman who tricked a man was a whore. If a woman tried to trick a man but failed and then was tricked by him, that was whoredom twice over. Kill her and you’d only dirty the knife.” (Chang 152)

“The Golden Cangue”

(Novella)

The golden cangue is the central symbol of the novella, but what is it? A cangue is an instrument of public shaming consisting of two heavy pieces of wood with a semicircular cut in each. The two pieces are fitted around the criminal’s neck and chained together. Hands and feet might be shackled as well, but in most cases, being trapped in a cangue for any length of time is miserable enough. In Zhang’s novella, we meet a very traditional Chinese family as it transitions into the modern era. The central character, Ch’ich’iao, is the daughter of a sesame oil seller. She was to be sold off as a concubine to the Ch’iang family. Instead, the Ch’iangs opt to marry Ch’i Ch’iao to the Second Master. The Ch’iang’s decision is strategically self-serving: Second Master is a “cripple” suffering from “bone tuberculosis:” Ch’i Ch’iao will be Second Master’s caretaker and wife. Ch’i Ch’iao is eternally bitter, cursing her parents for making such a match, deriding her frail husband, and tormenting everyone in the Ch’iang’s household. Despite her husband’s illness, they have a son and a daughter. But Ch’i Ch’iao does not have a mother’s heart. As she matures, she begins to smoke opium. When her husband dies, she attempts to reignite a smoldering affair with the Third Master, though even this lustful paramour wisely chooses to keep his distance from this gossiping shrew. Isolated and self-isolating, she sets her eyes on her young son, who, although married to Chi-Shou, has reached an age where he is falling for Chinese opera singers and pursuing prostitutes. To keep him near to her, she binds him to her as the preparer of her opium. Soon, just like his mother, Ch’ang-pai is spending his days inside with his pipe. Ch’i Ch’iao’s notorious reputation spreads throughout the community, with the result that no matchmaker or parent will consider Ch’i Ch’iao’s daughter, Ch’ang-an, as an appropriate match. Miraculously, when she reaches her thirtieth year, a suitor appears: the older T’ung Shih-Fang has been engaged twice and he has all but given up on finding a traditional Chinese wife. Yet, after returning from studying in Germany for ten years, he finds himself quite pleased by Ch’ang-an. The couple is awkward together, but the closer they become the more viciously Ch’i Ch’iao insults her daughter. Eventually, Ch’i Ch’iao’s madness overtakes her. What will happen to this doomed family? If the story’s style and plot are reminiscent of court romances, it is because Zhang Ailing drew inspiration for “The Golden Cangue” from the 18th-century classic, The Dream of the Red Chamber.

After the engagement Ch’ang-an furtively went out alone with T’ung Shih-fang several times. The two of them walked side by side in the park in the autumn sun, talking very little, each content with a artial view of the other’s clothes and moving feet. The fragrance of her face powder and his tobacco smell served as invisible railings that separated them from the crowd. On the open green lawn where so many people ran and laughed and talked, they alone walked an enchanted porch that wound endlessly in silence. Ch’ang-an did not feel there was anything amiss in not talking. She thought that this was all there was to social contact between modern men and women.” (223)

“Sealed Off”

(Short Story)

On a hot afternoon in a crowded tramcar in Japanese-occupied Shanghai, a romance briefly flashes into existence. The city is sealed off; when a siren roars, all traffic stops. In the artificial quiet, Lu Zongzhen, a low-ranking businessman dissatisfied with his wife, spots a nephew making his way toward him from the far end of the tram. Lu suspects the grinning nephew is approaching him to lobby for the opportunity to marry Lu’s thirteen-year-old daughter. In order to escape an awkward scene, Lu moves his seat and hides behind a pretty girl. Zhang allows us to hear the tentative, yearning thoughts of the twenty-five-year-old professor of literature, who is pretty but is dressed in a way that reminds the businessman of an obituary. Her fantasy and his fantasy briefly intertwine. A military truck passes by so closely that the passengers can look into the eyes of the Japanese. The all-clear signal rings out, and the businessman disappears into the crowd. This is an exquisite, tightly-restrained short story, a classic of the form.

“Gradually the street grew quiet too—not a complete silence but voices turned blurry, like the soft rustling of a marsh-grass pillow, heard in a dream. The huge, shambling city sat dozing in the sun, its head resting heavily on people’s shoulders, its drool slipping slowly down their shirts, an inconceivably enormous weight pressing down on everyone. Never before, it seemed, had Shanghai been this quiet—in the middle of the day! A beggar, taking advantage of the breathless, birdless quiet, filled up his throat and began to chant: “Good master, good lady, kind sir, kind ma’am, won’t you give alms to this poor soul? Good master, good lady…” but soon he stopped, overawed by the eerie quiet.” (Chang 238)

“Red Rose, White Rose”

(Novella)

From the start, Zhang’s narrator adopts a masculine point of view, averring—or confessing–that all men have two women in their lives: one, a wife, a spotless white rose, the other a passionate mistress, a vivid, red rose. To illustrate this phenomenon, the narrator introduces us to Tong Zhenbao, an “ideal modern Chinese man.” Educated in England, he studied factory management. He is now in upper management at a foreign-owned textile company in Shanghai. While in England, he felt starved for opera, so he traveled to France, where he saw the opera and took up with a Parisian prostitute. The experience left him feeling dirty. On returning to England he found himself seeking out mixed-race women, as he felt the Chinese were prudish and churchy; he preferred “girls who were a little more forthcoming.” In Edinburgh, he meets Rose. Her father was an Englishman who met his Cantonese wife while working in southeast China. He carries on a mostly chaste affair with Rose for many months, but his interest fades and he wonders, as beautiful as she is, that her mixed birth might not be to either of their advantages when he begins his career in Shanghai. Once back in China, he and his brother Dubao need a place to live. An accommodating friend from the textile factory, Wang Shihong, offers to let a spare room in his home to the pair. Wang is married; Jiaorui is his wife. Like Zhenbao, she was educated in England. Her husband lumps her in with “the overseas Chinese.” Even after three years in Shanghai, her Chinese is weak and she is barely able to write. Zhenbao and Jiaorui are immediately attracted to each other. When her husband leaves town on business, they begin a reckless affair that culminates when Jiao Rui announces that she has sent a letter to her husband confessing her love for Zhenbao and asking for a divorce. Zhenbao is taken completely by surprise. How can he marry this woman? She will be a disadvantage to his career and his mother will loathe her. He breaks off the affair and rushes home where he adopts a more Confucian model: he allows his mother to set him up with a college-educated but very traditional Chinese girl, Yenli, a young White Rose. Throughout, Zhang not only skewers both men and women when it comes to desire, love, and marriage but also explores mainland stereotypes about mixed-race and “overseas Chinese,” changing attitudes toward sex and marriage, as well as the way marriage choices can make or break a man’s career.

“The breeze was cool on his skin: most likely his face had been pretty red a moment before. Now he was even more troubled. He’d just put an end to his relationship with Rose, and here she was again in a new body, a new soul—and another man’s wife. But this woman went even further than Rose. When she was in a room, the walls seemed to be covered in red chalk, pictures of her half naked, on the left, on the right, everywhere. Why did he keep running into this type of woman? Was it his fault that he always reacted the way he did? Surely that couldn’t be. After all, there really weren’t that many women of this sort, not among the pure Chinese.” (269)