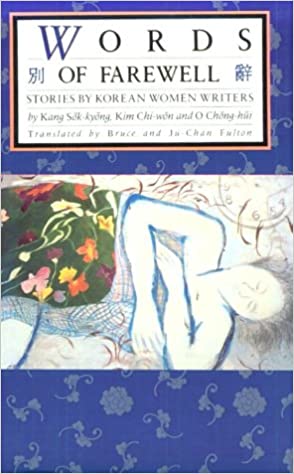

Words of Farewell: Stories by Korean Women Writers

Edited and Translated by Bruce and Ju-Chen Fulton

(1993)

Seal Press

(Short Story Anthology)

This collection features short fiction published in the late 1970s and early 1980s by Kang Sok-kyung, Kim Chi-won, and O Chong-hui.

“Days and Dreams,” by Kang Sok-kyong (1983)

Ms. Kang sets her story during the late days of the Korean War in the bars and brothels around an American base. The narrator works at a bar; though she may or may not be a prostitute, she has an ongoing relationship with an American soldier. The story begins with her discovery that she has contracted a venereal disease from her lover, who has been unfaithful to her. She takes an overdose of sleeping pills, gets drunk, winds up in a hospital, and breaks into a filthy clinic in order to be treated for the disease. During this period, she relates the stories of the other girls and women who are caught up in the various extra-legal activities around the base. The most developed of the stories involves the narrator’s encounter with a Black nurse who arrived from Japan to practice emergency medicine. According to the narrator, she is a lesbian looking to develop a relationship with a Korean woman. She promises that if she finds the right woman she will arrange for her to fly to the United States, where, according to her, they will be married. The prostitutes are completely baffled by the idea of sex between women, but one of the older women believes she will explore the offer as a way to escape the life she lives in Korea. The author thoroughly researched life in the American Zone; as a result, the story is a mix of frank and shocking realism and the innocence of uneducated youth.

“A spring scene of an ancient palace with forsythias in full bloom had replaced the mountain villa with smoke coming from its stone chimney; and so winter was torn from the calendar on the wall in the corner. A week later, I flunked my checkup. That happens a lot in this part of town, but I was really sore about it.” (1)

“A Room in the Woods,” by Kang Sok-kyung (1986)

The primary characters in this family drama are two sisters in the Yi family. The older sister graduated from college, earning a degree in Music, and took a job at a bank. She had no career aspirations; instead, she saved money while waiting to find “Mr. Right.” After four years, Mr. Cho’e arrived; he is now her fiancé. She left the bank and is preparing for her wedding, giving her the opportunity, for the first time in years, really, to think about her family and get to know her little sister, So-Yang. As it happens, So-Yang is in need of more than attention. As the story opens, we learn that she was robbed while carrying her tuition money to the university bursar. A page later, she confesses that she just dropped out of school, and soon it becomes evident that she stopped going to school last spring. It may even be possible that she staged the robbery and spent the tuition money. Fearing for So-Yang’s safety, the older sister calls a locksmith and gets a second key to her sister’s bedroom. She spends the days before her marriage reading So-Yang’s diary, surprised by her mercurial moods and becoming increasingly concerned about her state of mind. She interviews her sister’s friends, visits the bars and tea houses she frequented, and learns many of her secrets. She also finds time to wander all night in the discos, bars, streets, and back alleys of Changno, the district favored by disaffected high school and college students. At twenty-seven years old but passing for twenty-five, Mi-Yang wanders all night on the eve of her wedding as if she is trying to discover not only what So-Yang is seeking or why Mi-Yang opted to stop searching and become a wife. At the same time, we begin to understand the depths of So-Yang’s suffering, we also realize she is not the only family member who has taken secrecy to an extreme. While Mi-Yang awakens to the truth that her family is terribly dysfunctional, we realize that she tells us next to nothing about her relationship with her future husband. Mi Yang also digresses from her analysis of her sister to tell the story of a sexual assault at age twenty-something so horrific that it reads like it came out of a psychological thriller–and then returns to So-Yang’s diary with an uncanny sang-froid. What’s behind the silence in this family? Is it the family patriarch, who becomes increasingly angry and violent toward his disobedient child? Is it the intense competition that pits brothers and sisters against one another to excel in academic glory? Or are Koreans particularly vulnerable because of the nation’s lack of power and authority on the geopolitical stage? How can a nation’s people achieve a sense of self-determination if the nation itself is pushed and pulled in directions contrary to its own wishes?

Historians will be interested to know that the young women in the fictional Yi family are not alone in their search for a cause to live for: Kang situates the climax of her short story in the aftermath of nationwide student protests in 1988. Over 2,000 students in 22 schools protested against American and Japanese influence, burning effigies of President Reagan and Prime Minister Nakasone.

“Brats these days caused problems because their stomachs were too full, father went on. His generation had survived a war, stepping over the dead bodies of their buddies. After the war he had wandered the mountain villages of Kangwon Province with a rucksack searching for food for his family. He had then started a factory that made nylon socks, and now he had a factory that produced sweaters for export. In all that time he had never been able to stretch his legs and relax. And so father recited the history of his life. He hated to see the cheeky mugs of those little brats with their make-believe ideologies and useless demonstrations, doing whatever they wanted. ‘Get out of my sight,’ he finally shouted at So-Yang.” (49)

“A Certain Beginning,” Kim Chee-Won (1974)

Ms. Kim’s heroine is Yun-Ja, a divorced woman living in Manhattan’s Chinatown. She had lived all her life in Korea and married there. She gave birth to a child who died before its first birthday. One day her husband came home and announced that they should divorce. At first, she was convinced that he was seeing another woman, but she eventually concluded that he was simply bored with her. Having lost face, she goes to the US to escape her shame and begin a new life, but she finds her world lonely and exhausting. She works all day as a seamstress surrounded by Mandarin-speaking co-workers whom she does not understand. She struggles to make ends meet and fears she will end her life like the lonely old Korean woman she passes every day who shares her litany of woe with anyone who happens along the sidewalk. Her situation takes a radical turn when a friend introduces her to a man fifteen years her junior who has been caught overextending his student visa. Desperate to secure a Green Card, twenty-seven-year-old Chong-Il offers her $1,500 to agree to “marry” her. Both parties make a commitment to convince the authorities of the authenticity of their marital relationship while also sleeping at separate addresses, but as the final days of their “contract” approach, both Yun-Ja and Chong-Il begin thinking and behaving in ways that suggest that they might enjoy being married to one another, yet both are ashamed and scandalized that they could possibly be having feelings that are decidedly non-traditional and beyond the pale of acceptable Korean conduct. Have they lost their minds, or has their chaste relationship allowed for something unexpected to blossom?

“’Life begins all over after today,’ Yun-Ja thought. She had read in a woman’s magazine that it was natural for a woman who was alone after a divorce, even a long-awaited one, to be lonely, to feel she had failed, because in any society a happy marriage is considered a sign of a successful life. And so a divorced woman ought to make radical changes in her lifestyle. The magazine article had suggested getting out of the daily routine—sleeping as late as you want, eating as much as you want, throwing a party in the middle of the week, getting involved in new activities. ‘My case is a bit different… ‘” (149)

“Lullaby,” by Kim Chee-Won (1979)

In “Lullaby,” Ms. Kim follows a middle-aged couple who are also seeking a new life. In this case, the marriage is intact and there is a young child: a three-year-old girl. The couple had the child late in life and the wife is now anxious to escape their tiny city apartment. For months she has imagined escaping to a house in the country, someplace where she might be able to avoid her critical and abusive husband, perhaps a place with a garden. And she finds it: a lovely home built on traditional lines with a pond, well-water, and an established garden. Ms. Kim’s heroine thrives in this environment, embracing the natural world and the gentle rhythms of this new life. Unfortunately, the bucolic setting comes with a rumor of an old curse. Some claim that at night a chorus of voices can be heard from the pond, while others recall a series of tragic deaths at the home. But could such nonsense be true? The wife can think of half a dozen reasons why she should ignore the old tales. Unfortunately, though, her fantasy that a larger home might allow her to avoid the cruel eye of her husband proves to be precisely that–a romantic illusion.

“Longing for something to sustain and steady her, the woman nevertheless tended to doubt the permanence of everything. Do flowers last more than ten days? And floods that look like they’ll sweep the world away are gone in a couple of days, aren’t they? But her relief that the world was transitory was tempered by the painful realization that society expected marriage to be the most harmonious of human relationships.” (174)

“Evening Game,” by O Chong Hui (1979)

Ms. O’s “Evening Game” takes place in a dark and claustrophobic house inhabited by a broken and wounded family. O exploits the idea of the empty routines that pass for relationships or expressions of love in the lamplit dark of a house that seems to shift in time and space. The heroine is a middle-aged, single woman who appears to be her aging father’s caregiver. He is distant, critical, and prone to violent outbursts. During their spartan dinner, the father curses his absent son. His daughter does as well, though she also misses her brother. Where has he gone and how long has he been absent? Is he in his room now, refusing to come out? Bit by bit, we also learn that the heroine’s mother had a third child who was born with hydrocephaly. What became of those two? O does not reveal everything at once and she is content to fold ambiguities and shocking allusions into a story which is after all just a tale of an old man and his daughter playing cards at a kitchen table, the same as they have been doing since forever. But what of the whistling in the dark coming from the home for delinquent boys or the nearby construction site? Does she couple with these boys and men, as she hints, finding fulfillment enough in stolen moments of intimacy? Or are these scenarios, like so much in her life, merely fantasies?

Those who know their way around a deck of cards may be interested that the father and daughter are playing with traditional Korean playing cards called “Battle of Flowers.”

“The window had become black as carbon paper. Despite the light above the table. I felt that father and I were sinking into the darkness. It seemed like we had been sitting opposite each other playing flower cards like this since the distant past. My memories of the time before that were remote and confusing—a mixture of reality and fancy—a childhood dream. Like a gambler who leaves to go to the bathroom when he’s in a fix or the cards go against him, Brother had stolen away from his seat to see what his cards had in store for him.” (190)

“Chinatown,” by O Chong Hui (1979)

O’s “Chinatown” is told through the eyes of a young girl whose family has become displaced people in the wake of the Korean War. They had been scraping by on a ramshackle farm, but their cagey father has managed to find a spot in western-style housing down by the pier of an unnamed port city. The air is filthy with coal dust, causing the matriarch of the family to forever laud the purity of the water of the river she grew up by in the North. These families are the poorest of the poor in the post-war economy. The children sustain themselves on scraps. When they attend school they are singled out to be checked for lice and they are routinely dosed with homemade remedies to rid them of worms. This is the world where the young heroine comes of age, caring for her siblings, running errands in Chinatown, nursing her mother, and making friends with other refugees, including Ch’i-ok, the delightfully life-loving daughter of one of the prostitutes in the brothel next door. There the two explore their mother’s collection of costume jewelry and clothing, impersonating grownups. Ch’i-ok and the narrator explore the ruins of the city, watching men and women use pickaxes and other hand tools to tear down bombed-out brick walls and carve out a spot on which to build themselves a new home. As appealing as Ch’i-ok is, she does not dominate all of the narrator’s time. Before long, our young heroine realizes she is drawn to a young Chinese boy who seems as interested in her as she is in him. What will come of this first love in the ruins of three civilizations? A caveat: a villain appears in this story: a brooding, homicidal African-American soldier the girls refer to as “the darky.”

“Mother became pregnant with her seventh child. Only fresh oysters and clams could soothe her queasy belly, so every morning before school I would take an aluminum bowl and set off over the hill for the pier. I would dash by the firmly shut gates of the houses on the hill, sneaking glances at them out of curiosity and avague anxiety, for these were the houses of the Chinese.” (211)

“Words of Farewell,” by O Chong Hui (1981)

O’s “Words of Farewell” center on Chong-Ok, who, with her mother and young son, set off on a journey to visit the gravesite her mother and father purchased for their final resting place. Coincidentally, just before their departure, a group of lepers approaches the house begging for alms. Chong-Ok offers the group a few coins as her mother prepares to daub salt on the doorframe and gates. It is a jarring moment, one of many that highlight the tension between the ancient world of haunts and portents the mother occupies and the modern world her daughter lives in. As in many of O’s stories, the people who are absent are as important as the people we meet. Where is Chong-Ok’s husband? Sometimes, in flashbacks, Chong-Ok recalls cryptic phone conversations. It seems as if someone is trying to locate her husband, but the caller seems to never find the man at home. He is always elsewhere. Is the husband hiding from loan sharks? Is his life in danger or has he simply abandoned all of his responsibilities? At one point, after Chong-Ok perhaps gives too much away, her husband simply cuts the phone cord with scissors. Yet as we follow Chong-Ok on her journey to her parent’s grave, we also see the husband as he purchases a full fly-fishing kit and makes his way toward a river that seems to call to him. When the mother arrives at the cemetery, she discovers it to be run-down. The caretakers are uninspired, the grounds overgrown, and the gravesites she purchased years ago seem too small to contain her and her husband’s coffins. O’s experimental storytelling is challenging and thought-provoking enough, but the story is also worthwhile for those interested in the rituals of death in Korea. Chong-Ok’s mother’s interest in familiarizing her daughter with the plots is significant for many reasons, not the least of which is the spiritual loss inflicted by the war that never ended: her family’s ancestral burial place is completely inaccessible to her: it is in the North. Because of the war, the family may never truly be “home” until the day when their bones can be dug up and moved to ancestral lands. That truth is underlined when the family pauses to observe a significantly larger group inter their beloved. The men are in black and the women are dressed in white. According to Chong-Ok’s mother, because they are southerners and fear that the bones of the deceased will be discolored by the coffin’s wood, the family unwinds the cloth wound seven times around it and carefully removes the body. From where they stand, they can see the seven holes in the body’s shroud, cut to symbolize the Big Dipper. Then the men lower the body into the grave and set fire to the coffin. While it burns, the gravediggers chant, filling the hole with layers of dirt and lime, tamping it down, and adding more layers. When the hole is filled, they pile dirt in a high mound, finally covering their work with turf. Chong-Ok’s mother reveals more touching rituals, perhaps the most moving custom being that when couples are buried, a pathway is dug between the two coffins so that lovers can visit one another. The allusions to the old ways pile up, with her young son engaging with a solitary bird and a flock of numberless black birds obscuring the sky above the cemetery. As in many of O’s tales, one has a sense that she is working in a kind of magic realism or attempting to reintroduce the shamanistic powers of the past to drive out the pain of living in the modern world.

“The magpie flew freely in the still white void and then returned to earth, the desolation of midday seeming to weigh heavily on its steel-colored wings. Every time it hopped from one gravestone to another the boy would approach it…When the boy finally gave up and dropped his arms to his side, the magpie flew near keeping close enough to sustain its opponent’s interest. The bird now had a firm grip on the boy. It was casting its net and enchanting him.” (258)