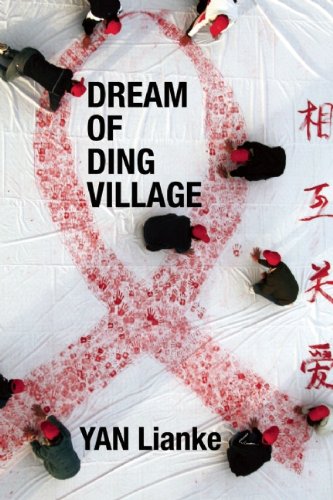

Dream of Ding Village, by Yan Lianke

Translated by Cindy Carter

(2006, translated 2012)

Grove Press

(novel)

Dream of Ding Village is a fictional account of China’s deadly “Plasma Economy.” From 1991 to 1995, the Henan provincial government instituted an aggressive program to encourage citizens to sell their blood for ready cash. The demand for blood came not only from hospitals but also from an explosion of medical startups. Although most blood transfusion sites were legitimate, many were not. Unscrupulous businessmen economized by reusing needles and other equipment. The most willing to sell their blood were often the poorest; blood harvesting clinics popped up in small towns and villages in rural areas. The program drew three million donors. Of that population, as many as 40% contracted AIDS. The narrator of the story is the only son of Ding Hui, the most powerful “Blood Head” of the region. Ding Hui brought the scheme to Ding Village and persuaded its people to sell their blood. He was able to pay them more money than they had ever seen and the quality of their lives improved tenfold, but they soon found themselves sick with “the fever.” Ding Hui is an unrepentant scam artist. He underpays the donors and sells their blood at a major profit. When the government sends food to the village, Ding Hui, siphons off the lion’s share and sells it on the black market. When deaths spike, the government donates coffins, which Ding Hui sells to the impoverished citizens. It should come as no surprise then that Ding Hui’s son, the narrator, is dead, having been poisoned by townspeople seeking retribution against Ding Hui. As is necessary, the novel is chock full of tragedy, but heroes appear. Ding Yuejin, Ding Hui’s brother, contracts the disease. When he leaves his wife to quarantine at the village school, he and Lingling, who is also dying, begin a passionate romance that matures into an ennobling love. Yan also allows the local storyteller/folksinger the opportunity to deliver a transcendent final performance. The greatest hero and the conscience of the novel is the patriarch of the Ding family, Ding Shuiyang. Part school teacher, part school janitor, he witnesses the venial conduct of his son and begs him to confess to the people. Like a Greek chorus, as the dying citizens descend into self-serving greed, he alone expresses shock, he alone asks them to reconsider their actions. The novel is banned in China; Yan claims that it would have been a better novel if he hadn’t been self-censoring while writing it.

Staring at the smoke rising from the school, which now seemed not so white but tinged with silver and gold, it had dawned on him, that with so many deaths in the village, with so many people sick and dying, the higher-ups would have to take action, do something to show their concern. The government would have to do something for the people of Ding Village. It couldn’t just ignore them. It couldn’t stay silent, blindly doing nothing. Because who ever heard of a government that saw and heard nothing, said and did nothing, took no action and showed no concern? (114)