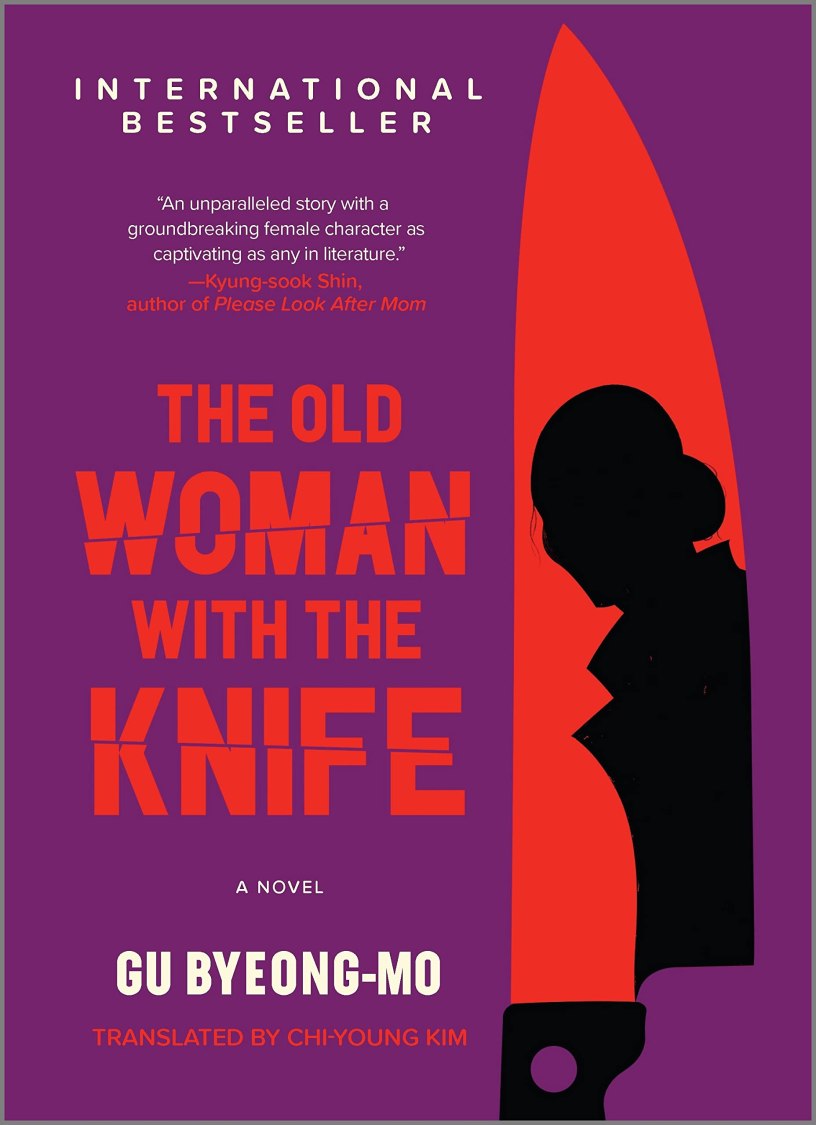

The Old Woman with the Knife by Gu Byeong-mo

Translated by Kim Chi-yong

(2013, translated 2022)

Hanover Square Press

(Novel)

Perhaps by coincidence alone, a significant portion of the books and short stories I have read from East Asia focus on the plight of the elderly, so I was not so surprised to be introduced to the elderly female protagonist of The Old Woman with the Knife. Like many women of her age, she is aware that she has long been invisible, unnoticed, and forgettable as she goes about her work. As she looks ahead to her retirement, she worries over her health, her aches and pains, and wonders if her recent forgetfulness is a sign of the onset of dementia. She worries if she has saved enough and frets that she will be forced out early as her employer seeks younger, less expensive workers. For most of her life, she has been independent. She lives alone, has neither lovers nor friends, and though she has been perfectly content with her life for decades, she discovers for the first time that she may be lonely and may even be feeling a desire to love and be loved. Orphaned, abused, and exploited, she has kept herself gainfully employed as a professional assassin. She has outlived many of her managers and is beginning to sense that a new hire is out to humiliate her and take over her assignments. The stress is causing her to lose sleep, and while attempting what should be a simple murder for hire she finds herself gravely injured. She only just manages to make it to the offices of a doctor who is paid to tend discreetly to the wounds of the company’s killers but is instead treated by a young intern who happens to be in the right place at the wrong time. No fool, the physician realizes that his elderly patient has fled a crime scene and infers that as soon as he sews her up she will silence him. To his surprise, she does not. But she regrets her weakness and the next day she begins stalking the doctor, his wife, their daughter, and his elderly parents. The old woman, whom we know only by her professional alias, spends the rest of the novel trying to avoid arrest for her botched attack, fend off the cruel barbs of her youthful competitor, and determine precisely how to eliminate the one person who could connect her to the crime: the hapless physician. The story is short and fast-paced. It is a perfect example of Korean noir, with the added bonus that it provides brilliant commentary on the plight of aging women in a world that prizes youth, health, and perfection.

“The only time anyone pays attention to senior citizens on the subway is when they bump into people as they carry a bundle of discarded newspapers scavenged from one end of the train to the other, or because they’re decked out in baggy, purple polka-dot pants, and lugging a pungent bundle of ginger and sesame oil, loudly announcing, “Ouch, my back!” until someone offers them a seat. Sometimes it’s for the opposite reason—an older woman forgoing the short, permed style common among the elderly and instead boasting straight white hair to her waist, sun spots inexpertly concealed with powder and eyeliner drawn with a wavering hand, or, even worse, wearing bright red lipstick or a miniskirt suit in pastel colors. The former type of elderly citizen evokes disgust while the latter is so incongruous that onlookers are mortified; regardless, both are one and the same, as people don’t want to think about them.”