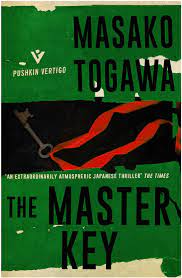

The Master Key, By Togawa Masako

Translated by Simon Grove

(1962, translated 2017)

Penguin Random House

(Mystery Novel)

By any measure, author Togawa Masako led an interesting life. She had a career as a singer/songwriter, wrote a number of best-selling mysteries, and made a name for herself as a feminist and champion of LGBTQ causes. She was raised by her mother in an apartment building that rented only to unmarried women, and it is in precisely this single-sex environment that she sets The Master Key. The owners, the entire staff, and all the residents of “The K Apartments for Ladies” are women. The building survived both the Great Kanto earthquake of 1923 that struck Tokyo and Yokohama and the bombing of the Great War of the Pacific. Although the original purpose of the building was to house young women who were coming in from the suburbs or the country to work in the city, thirty years on the occupants of the buildings tend to be those early residents who never married. As the story opens, Tokyo is undergoing a major public works initiative to improve traffic and communications by widening the city’s ancient streets. As a result, contractors have been slowly lifting the K Apartments for Women off its foundations in preparation for moving the five-storey building. The construction will expose the basement of the building, where, as we learn in the opening pages, a corpse is buried. However, the building houses more than one crime and many more mysteries. A mad hoarder stalks the halls in quest of bones, a mysterious religious leader and his divine, the lady Thumbelina, have been making inroads in the community, acquiring a host of followers, a retired schoolmistress has reconnected with a former student of hers who lost her young mixed-race son to kidnappers, and a former concert violinist has had a precious instrument stolen from her. Moreover, in the past weeks, the master key that provides access to all the apartments has been pilfered on at least three separate occasions. The narrative is cleverly structured and the lives of the characters reveal the way unmarried women of the time made their livings and passed the time of their retirement. There is also an interesting commentary on the American influence on Japan’s political and social reconstruction after the war as well as the complications arising when American soldiers married Japanese women.

“All trace of envy or sense of inferiority towards Toyoko Munekata had melted away on seeing those pitiful manuscripts, but she had no sense of triumph from laying bare her adversary’s secret. She only felt as if the bonds of circumstance which had linked her to Toyoko for so long had been cut, and she was on her own in a world of darkness and aimlessness. She felt that she would have been better off in her previous ignorance. Suddenly she felt hatred and anger towards the man who had telephoned her. Why had he done it? (44)