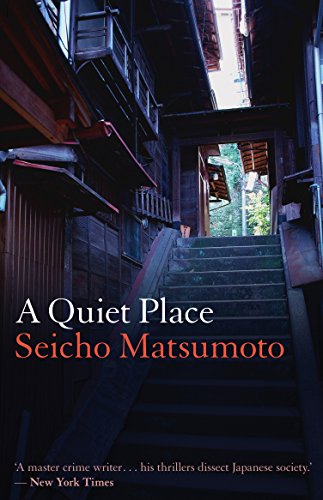

A Quiet Place, by Matsumoto Seicho

Translated by Louise Heal Kawai

(1971, translated 2016)

Bitter Lemon Press

(Crime Novel)

Matsumoto is an interesting writer. He focuses primarily on the inner world and the psychology of the criminal–something very new at the time– while also turning a critical eye on the culture of corruption in post-war Japan. He loathes Japan’s embrace of capitalism and blames the decline in Japanese values on the nation’s attempt to emulate the United State. For example, when a man is found dead on a remote hillside, newspaper and magazine writers are quick to draw a line between rumors of a neighboring hippie enclave to Charles Manson and the Sharon Tate murders, reasoning that the US is poisoning Japanese culture with its own blend of hedonism, greed, and nihilism. The protagonist is a civil servant who specializes in agriculture and meat production. The modernizing forces Matsumuto observes are not merely the result of soft influence. His hero is part of a government effort to prevent farmers from overproducing rice and switching to the production of meat and meat byproducts–in effect, he is an agent of a radically new approach to land usage and his work will radically change the economy, diet, and tastes of the Japanese. A tragedy strikes early: He is away on business when his sister-in-law calls him to report that his wife died of a heart attack while ascending a hill in Yoyogi. Reluctant to leave his meeting prematurely, his employer urges him to immediately return to his family. As he reflects on his wife’s life and death, he takes a practical point of view. Theirs was not a loving marriage, their bed had grown cold, and she had done little to support him in his career. Not surprisingly, he quite quickly begins to consider how to go about finding her replacement–he even reveals an interest in his wife’s sister, whom he always found more attractive. Male friends encourage him to join them on business trips where they will be sure to visit geishas and brothels, while women urge him to find a new spouse. Instead, a terrible suspicion enters his brain. True, his wife had a weak heart and everything about her death at a young age seemed relatively ordinary, but after the prescribed period of grieving, the bureaucrat, Asai Tsuneo, begins to pull at odd details from his wife’s itinerary on the day of her death as well as inconsistencies in the reporting of her death. Eventually, he comes to suspect that his wife, who was exceptionally careful to avoid straining her weak heart, might have been cheating on him. Why on earth would she risk climbing that hill, where there were not one but two hotels notorious for lover’s assignations?

“Ever since the streets of Yoyogi had been redone for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, the character of the area had changed completely. Still, if you got off the main roads, there was some of the old atmosphere left. Here and there you caught traces of the steep slopes that the artist Ryusei Kishida had depicted in his 1915 painting Kiritoshi no shasei (“Road Cut Through a Hill”). Obviously, that famous view of uneven red earth had long since become grey asphalt, and there was not a single tuft of wild grass to be seen, but long expanses of the famous stone walls had been repaired and lined both sides of the street. Luxury homes and grand apartment buildings filled the empty land beyond the walls. The desolate landscape that Kishida had fallen in love with when he first moved to Yoyogi in the early part of the twentieth century was now a prime residential zone.” (31)