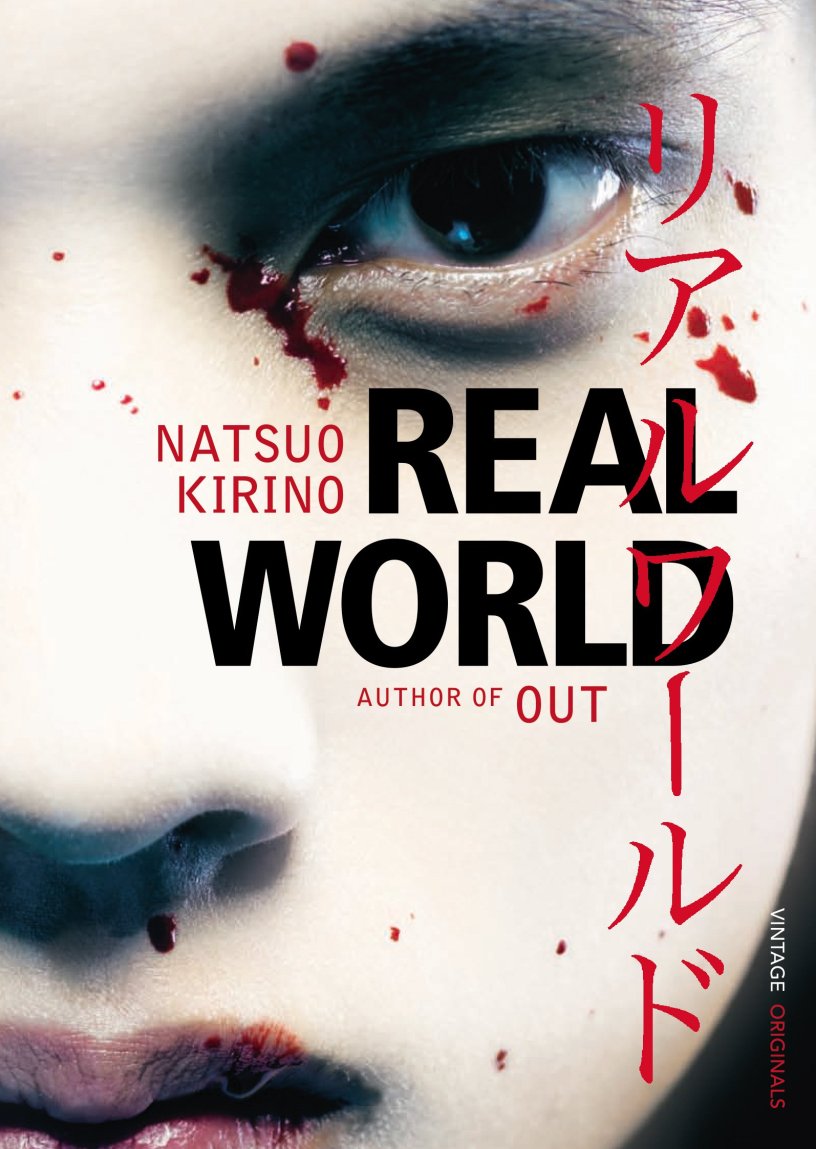

Real World, by Natsuo Kirino

Translated by Phillip Gabriel

(2003, translated 2008)

Vintage International

(Novel)

Ms. Kirino’s breakthrough novel was Out, published in Japanese in 1997 and in English in 2004. Her dark tale of vengeance is a masterpiece of Tokyo noir; when a woman strangles her abusive ex-husband, three of her coworkers at a bento factory collaborate to destroy the evidence. In Real World, Ms. Kirino again focuses on a collaboration between women. On a terribly hot summer day, just as a neighborhood smog alarm blasts, Toshi hears a thud next door. Immediately, she assumes that it must be Worm, a sullen, morose boy who attends the high-status K school. Leaving her house, she says hello to Worm for the first time, noticing that he seems uncharacteristically upbeat. Shortly after heading into town, she discovers that her phone and bike are missing. When she gets back home that evening, police have cordoned off her neighborhood; it appears that the neighbor boy has beaten his mother to death with a baseball bat. When questioned about Worm, Toshi denies having any interaction with him. Then it is revealed that Worm stole Toshi’s bike and phone. The night of the murder, out of boredom, he begins calling the girls in Toshi’s contacts. Ms. Kirino presents the story through the voices of five narrators: Worm, Toshi, Terauchi, a high-achieving student; Yuzan, a girl who is still grieving the death of her mother while edging closer to coming out as a lesbian, and Kirarin, a good girl who sneaks out at night to pick up men in the Tokyo club scene. None of the girls seem alarmed by Worm’s calls. Instead, they admire him for taking all of his privilege and destroying it. All of the girls have a high level of distrust for the adults in their lives and at least one fantasizes about murdering her own parents. While they criticize the hypocrisy of their parents, their own philosophies are shallow. The teens on the Japanese internet explode with praise for Worm, yet the murderer is weak and needy. He imagines himself as a heroic Japanese soldier from the Meiji period, awaiting orders to die in a heroic final battle. He can barely fend for himself and though he imagines his violent act will enable him to get a girl and have sex, he finds that murdering his mother actually changes little about himself. The story is unflinchingly cold-hearted. The only relief arrives in the denouement, when Kirino allows the adults to speak. At last, we hear the voices of reason and mercy. Even characters the young girls demonized show remarkable maturity, depth, and care. The female detective may be the most astute and delicate as she deals graciously and politely with the teens who aided and abetted a monster, but perhaps most moving is a letter from Wataru, a former lover of Kirarin. Ms. Kirino’s use of multiple unreliable narrators requires careful attention, the violence is graphic and cold, but the novella is hard to put down. Incidentally, Natsuo Kirino has written non-fiction about Japan’s “love hotels.”

“The siren keeps on droning. Right in between one of its groans, I hear a loud sound, something breaking next door. Our houses are so close that if you open the window, you can hear the parents yelling at each other, or the phone ringing. I’m thinking maybe a window broke. Seven years ago the boy who lives in the house diagonally across from us kicked a soccer ball that shattered a window in our house in the room where we keep our Buddhist altar. The kid completely ignored what happened, and later on he was transferred to a school in Kansai. I remember the abandoned soccer ball sitting there under the eaves of my house forever.”