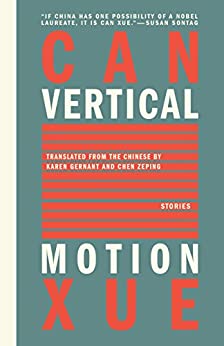

Vertical Motion, by Can Xue (real name Deng Xiaohua)

Translated by Karen Gernant and Chen Zeping

(2011)

Open Letter

(Short Story Collection)

The author’s pen name means “leftover or soiled snow.” She is an avante-garde writer with a long writing career, a woman who has endured significant criticism over the years by male writers and critics. The short stories in this collection were previously published separately in magazines.

“Vertical Motion”

The narrator is a subterranean creature burrowing through rich black earth. Descriptions of its body suggest that it is a worm, yet its growing proboscis indicates it might also be a bird. There is community underground, but no intimacy; creatures seem repulsed by the idea of touching one another. They can communicate via vibrations through the earth, sharing stories and mythologies. The narrator remembers a father, but he has not been seen in years, and there is a collective mourning for the mysterious disappearance of a patriarch, a great explorer who may have reached the storied surface world. The creature commits to a quest for the upper regions, guided only by its sense of gravity.

“I’m an average-sized, ordinary individual of my genus. Like everyone else, I dig the earth every day and excrete. Recalling our ancestors is the greatest pleasure in my life. But when I sleep, I have some odd dreams. I dream of seeing people; I dream of seeing the sky above. Human beings are good at movement. They feel bumpy to the touch. I’m extremely jealous of their well-developed limbs, because our limbs have atrophied underground. We all move about by wiggling and twisting our bodies. Our skin has become too smooth, easily injured.”

“Red Leaves”

The narrator is a teacher, Gu, who is being treated for an unspecified disease of which he may be dying. His hospital ward is a nightmare. The previous evening, after learning that he would experience a full recovery, a patient jumped out of bed and threw himself out the fifth-story window. Witnesses report that his last word was “Gu.” The man in the bed next to him is also dying, but when he suddenly feels well enough to walk the ward he is tackled by nurses and bound to his bed so tightly that he struggles to breathe and begins coughing up black blood. Gu suffers from acute hearing—or auditory hallucinations. Trapped in his bed and kept awake by the voices, he concludes that they must be “catmen.” Yearning to learn the source of half-heard arguments and whispered conversations, he manages to ascend to an upper floor where he meets a former student, a young man he admired because the child dove through the ice on a frozen river to rescue a classmate. The student and teacher bond; their shared affection for one another filling them with warmth and life.

“One red leaf floated in the air above the forest of his thoughts—a forest that was totally bare, for it was winter now. Gu had been pondering a question for several days: Did a leaf start turning red from the leafstalk, the color gradually spreading throughout the entire leaf, or did the entire leaf gradually turn from light red to deep red? Before falling ill, Gu hadn’t observed this phenomenon, probably because he missed the chance every year. In front of his home were hills where maples grew. But it was only after he fell ill that he had moved there.”

“Night Visitor”

Critics often point out that Can is influenced by writers like Borges and Marquez. Although there are clear indicators that this is a Chinese story, there were moments when I almost believed the mysterious house in the story was located somewhere in South America. The narrator, Rushu, who may be a middle-aged woman, is the trusted confidant and caregiver for her aging and ailing father. He is retired, though as far as anyone can remember, he may never have worked at all. He lives in a room in the back of the house. He has boarded up a door that opens onto a common courtyard. Though he is barely able to walk, if he must leave he must exit the house by going through the rooms of his children. And as inactive as he is, he seems to hold a disproportionate influence over his children. He occupies his days by pursuing some unknown research in the chaotic jumble of books that are the principal furniture in his room. Should Rushu knock on his door, she invariably hears the frantic shuffling and crashes of a man who is trying to hide something. When Rushu and her siblings agree that her father may need to be moved to a rest home, he accuses her of working against him and conspiring to murder him. He also begins to destroy his books, working deliberately with a pair of scissors. Around this time one of Rushu’s siblings reports that upon entering the courtyard one evening, she discovered that their father’s light was on and that he was deep in conversation with a tall man. Rushu takes it upon herself to investigate. Moving a shelf in her father’s room, she sees that the old door, warped with age, has been pried open. Although the father denies any such meeting took place, Rushu determines to stand vigil in the courtyard for several evenings after the initial incident.

“It’s hard for all of us siblings to get together. Usually everyone is busy. We only sit at the same table at mealtimes. Although we sit together, we don’t talk much. I think this is because Father is present. Looking at him, who dares talk and laugh freely? As I see it, when one is old, one should know one’s place and retreat from life. Paternalistic behavior won’t do him any good in the end. Sometimes, I can’t avoid thinking that this family isn’t a family anymore! It’s oppressive, disorganized, and unreasonable. Do any other families maintain patriarchy as we do?”

“An Affectionate Companion’s Jottings”

Perhaps inspired by Soseki Natsume’s I Am a Cat, Can’s narrator is a precocious feline. The animal makes a study of her eccentric master, an aging journalist deeply involved in the workings of a newspaper. Unmarried and unattached romantically, he is all but a hermit. Early in their relationship, the journalist is so preoccupied with writing projects that he often neglects to feed the animal. Later, the hungry cat finds himself trapped in the refrigerator; his absent-minded owner had not seen the cat leap inside when he opened the door and shut it, completely unaware that he had consigned his cat to a slow death by suffocation. The journalist happens to discover his error at the last moment and, guilt-ridden, vows to cook fresh meals for the all-but-frozen beast for the rest of his life. The cat witnesses the writer’s fits of productivity, his wheedling, cajoling, and desperate phone calls, and even discovers his master in the act of hanging himself—a gesture the owner explains away as an attempt to research the feeling of a suicide. The cat observes the journalist’s conduct as he receives visits from other newspapermen. Alarmingly, the cat also reports on the appearance of a character known only as “the black man.” This figure can occasionally be seen lurking outside, his presence indicated only by his shadow. When he enters the house, he terrifies the journalist. The unnamed visitor, whose skin is “like black lacquer,” converses with the journalist while writhing in agony, complaining that his chest was badly burned in a fire. When he shows the journalist his wound, he reveals his heart also; the organ beats outside of his chest.

“Old Cat, why did you have to offend my colleagues? You really should stop being so self-righteous. See, you learned a painful lesson this time. I also know that you purposely took the phone off the hook so that my colleagues couldn’t get through. Why did you bother? You must realize that even if they can’t get through on the phone, they can think of other ways to get in touch with me. No one can keep them away. Even though you’re one smart cat, you’d better understand that my thoughts are a lot more profound than yours.”

“A Village in the Big City”

“A Village in the Big City” is the name of the cramped twenty-four-story apartment building which is home to the narrator’s Uncle Lou, a diffident, hermit-like creature who inhabits the mostly glass structure on the roof of the high-rise. Anyone familiar with real estate advertising knows that names like Camelot and Sherwood Manors bedazzle the entrances to structures that were dated before they were even built and that offer tiny apartments with only the most essential conveniences. The same is true of this sham “village.” Not only is there no sense of community in the building, but the building itself also lacks connection from floor to floor. There is an elevator, but most of the building’s inhabitants use the stairs, which are sometimes there and sometimes not. Listening carefully as he chats with Uncle Lou, the narrator can hear the steady steps of a person as he ascends the stairs, stops at a landing, turns, and goes down again. Stepping out to get a breath of air, the narrator discovers there is no floor beneath him. The entire twenty-fourth floor hovers over the twenty-second floor far below. The apparently undecided stair-climber is down below, trapped in a staircase that is disconnected from both the floor above and the floor below. The narrator and Uncle Lou’s conversation likewise stops and starts. There are several attempts to recall past acquaintances, but these conversations likewise go nowhere, as either the memories of the two men are failing or they are each recalling a different person. Uncle Lou himself refers to the narrator throughout by the nickname of his deceased younger brother, Hedgehog. When the narrator reminds Uncle Lou he is actually the adult version of the child known as Puppy, Uncle Lou becomes irritated and stares off into the sky. A mystery seems to be solved: Was it Uncle Lou who stole the narrator’s playing cards long ago? But perhaps, no. The story ends with the blood relatives expressing regrets over their failure to take risks long ago, and the narrator trying to find his way out of the shifting, disappearing building.

“Had he floated out from the window? I went to the door again and peeped out. What I saw was still the view of the room in suspension. I took several cautious steps forward, and at once I was frightened into crawling down. I didn’t have the courage to stride out toward midair; even if I had studied Shaolin kung fu, I probably wouldn’t have dared. It was too dangerous; I had to rush back inside. I climbed back to the room, stood up, and brushed the dust from my clothes.”

“Elena”

A male narrator awaits the arrival of his lover. He lives in a modern apartment noted for its cleanliness. She arrives in the darkness to take his hand in her mouth, a sensation he claims is as intimate and as cold as the socket of a hip bone. As they talk of their long affair, she informs him that his pristine flat conceals rafts of cockroaches; he notices she grinds her teeth as if she is chewing on sand. Remembering how they met, she reminds him that she was called to him, leaving her parents behind in the mountains where she once flew. Later, they walk in the moonlight and kiss until she darts off into the night. The next morning, his neighbors ask after him; it seems he has been sleepwalking again. Days later, he agrees to follow his beloved to her home. She leads him through a maze of alleys jammed with peddlers and they land in a processing plant for ducks. The lovers crawl in the dark on a floor wet with the bodily fluid and viscera of slaughtered birds. Covered with blood and offal, Elena’s brothers appear. mocking her beloved and the stone that suddenly appears in his hands. When it moves, the narrator drops it; it screams once and dies, though a few moments later it appears to recover. The lovers escape the brothers and take shelter in a chicken coop where they embrace on a heap of animal dung. The chase continues and the lovers eventually find themselves first in a stockaded family compound and then in the winds that caress a mountaintop where the air smells of narcissus.

“I wasn’t very accustomed to the buoyancy of the air. I kept wanting to grab something to steady myself. There was a lamp post. I would hang onto it. My movement caused me to fall head over heels, and it was hard to turn around. When I looked again, I couldn’t see any street light; there was just a faint streak of light, that’s all. Elena’s voice still reached me now and then.”

“Moonlight Dance”

Can Xue focuses once again on the relentless tilling of the earth, at times on the surface, at times underground. On the surface, the narrator is fixated in admiration and perhaps horror by the lion on the opposite shore, who in turn watches the movement of a zebra. Despite the drama and tension of what-is-about-to-be, the attack that never comes, the narrator travels homewards to its field to till. Underground, it tills horizontally, a worm above and a worm below its only companions. In a fit of inspiration, perhaps in an effort to reconnect with a lost grandfather, it dares to dive straight down through the earth, tilling vertically until it reaches limestone. The worms behind cheer on the explorer. What will it do when it finds the tunnel?

“I couldn’t see the earthworms, and yet they were always with me. As soon as they came toward me, I sensed them at once, for in the depth of the soil, the sensors were subtle. I could even sense their mood. The one above me was brimming with enthusiasm; the one below me was a little depressed. They were both time-tested believers. What did they believe in? They believed in everything, just like me. It was a faith born of the source. We were the moonlight school. The dark field was the place where we carried out our faith.”

“The Roses at the Hospital”

The narrator has heard of Gaoling, of its poverty and filth, and so she travels there to see it with her own eyes. She sees children following coal carts and sweeping coal dust into dust pans so they can heat their homes. He climbs the hill, observes the funeral of a young girl, and encounters another girl who will serve as his guide to the hospital above the city. They find a gap in the wall and enter the hospital grounds while the sick and dying wave from above. His guide calls him onward, warning him to be careful not to trip on the children, some who are living and others who are dead. Turning a corner, they arrive at the hospital’s courtyard, which is alive with grotesquely giant roses. Few of Can Xue’s stories in this collection give a name to the setting, yet here the author specifically mentions Gaoling. There are Gaolings in Shandong and Shaanxi Provinces; there is also a Gaoling in Beijing, where the author resides. Are the hospital, roses, and slums a representation of the Southern Capital?

“But I didn’t want to go with her. I was afraid she would suddenly part the clump of flowers and make me look at that ghost-like thing. I suggested that we admire the flowers from a distance. Staring at me, she nodded in agreement. Ah, the roses! The roses! In the strong floral fragrance and under the gentle blue sky, I felt that I was in a fairyland! The wards next to the slums were so squalid, and yet a wonderland was hidden here. How could anyone imagine this?”

“Cotton Candy”

The narrator is one of a cluster of poor children who regularly crowd around an ancient woman who comes to town each day to spin and sell cotton candy. Obsessed by the magical quality of the sweet filaments the woman seems to pull from the air, the children observe her intently. At what point does nothing become something. The children even delight in watching others who can part with a few pennies as they eat the ephemeral confection. In truth, the narrator has tasted the cotton candy on several occasions, marveling at the way the stuff melted to nothing the instant it touched her tongue. And frustratingly, the narrator admits that what he tasted was nothing much of anything and certainly not comparable to the flavors extolled by the other children. That puzzle is eclipsed by another inexplicable phenomenon: the cotton candy vendor who sold this most desirable product had gone bankrupt. How could this be? And to complicate the mystery, she continues her route, setting up her tub-like contraption and repeating her focused spinning, “serving” the hungry children though everyone can see that her tub and her hands are empty. She continues this pantomime until her death, after which the children—perhaps in keeping her memory alive—engage in a rich economy of empty-handed exchanges.

“I’ve eaten cotton candy just twice. It was the most mystifying experience on earth. When I put that soft, transparent, fluttering white thing in my mouth, it vanished like air. It had no taste. I knew I’d seen that cotton candy was made of sugar, so why didn’t it taste sweet? I asked Amei and Aming, but they both laughed at me and said I was ‘miserable.’ In my anger, I started ranting and raving, and they ran off.”

“The Brilliant Purple China Rose”

Can Xue’s more humorous stories tend to focus on domestic dramas and the trope of the nosy neighbor. Mei and Jin have raised their children, and having achieved their goal, they have settled into a routine. They both suffer from insomnia. To avoid glare from the ever-increasing flow of traffic past their windows, they have covered every reflective surface in their house with matte fabric. The husband spends his day reading a book on botany while his wife tends to the ramshackle, jerry-rigged awning that shades the garden in which they have planted her husband’s special China Rose seeds. The neighbor Ayi visits regularly to mock the shabbiness of the awning and the likelihood that the precious seeds will never grow. The seeds are indeed special: they must be planted a foot beneath the surface, and they grow straight down and blossom far below the earth. A master propagator explains that the seeds are best planted haphazardly and then ignored. Yet as capricious as this plant might be, the neighbor Ayi is delighted to find a seed that has fallen to the floor; no doubt she will plant it and erect the requisite awning by nightfall.

“Mei told Jin that their neighbor Ayi didn’t believe they were growing the China rose. Jin was shaving just then, and lather covered his face. Blinking his little triangular eyes, he said he hadn’t believed it either, at first. Whether people believe it or not has no bearing on the China rose’s growth.”

“Rainscape”

The narrator sits in her room at night where she likes to “tally the accounts” while contemplating the dark stone façade of the building opposite hers. Some one hundred meters away it featureless face is broken by only two narrow rows of windows and a set of doors held shut by a golden lock. Both the woman and her husband her sounds of weeping from the building at night. They believe the sound may be coming from the rocky outcrop behind the building. They determine to explore this space in the daylight, the narrator comes across her brother. He is thinner than before. He still has not found a job and she does not know where he is sleeping. She invites him inside, where he slips into his usual silence, so reluctant to draw attention to himself that he slips into the shadows of a corner of the room while the husband and wife carry on a conversation about what has happened since the brother last visited. He excuses himself and heads off into the night as the crying continues. The couple continue their investigation while the woman reflects on the death of her other brother and the drifting, ghost-like wandering of the brother who just visited and who may or may not be sheltering nearby.

“I started seriously considering making an inspection behind the building. We hadn’t gone there since we moved here more than ten years ago, because there was a craggy hill behind the granite wall. My husband and I always thought there was nothing worth looking at. Before falling asleep, I mentioned my plan to my husband. He said vaguely, “What if you get lost?”

“Never at Peace”

The tale begins with the arrival of a visitor: after many years away, Jinglan has returned to renew his relationship with his beloved mentor, Yuanpu. On his arrival, he is heartbroken to find that his old friend’s health has collapsed. He is emaciated, his skin is gray, and he struggles to even sit up in bed. Jinglan is at a loss as he tries to unearth traces of Yuanpu’s intellectual fire while his mentor argues that his student is exaggerating his former prowess. As the two attempt to revive their relationship, Jinglan is witness to the strange behavior of Yuanpu’s servant for the last thirty years. This Wanmu is acting in a manner that seriously compromises the health of Yuanpu. She holds nightly meetings in the home, disturbing the old man’s tranquility and sleep. She also displays the symptoms of a compulsive hoarder, cluttering the old man’s home with useless material which seems valuable only to her. Wanmu even installed her own mother, another invalid, on the floor above Yuanpu. As Jinlang investigates, he discovers that until he had lost his mobility, Yuanpu had spent many nights crawling up the stairs in order to question the old woman: was her daughter trying to kill him? For her part, Yunma has her own sense that the old man is sabotaging her life. Much of her resentment seems to be rooted in his command that she help him use the bedpan for the last six months instead of walking to the bathroom. However, when Jinlang attempts to intercede in what he sees as a clear case of elder abuse, his mentor refuses his aid and argues that he now understands his servant’s role completely. From his perspective, all is in order. Yuanpu explains that Wanmu is now his mentor, even as she drags a coffin into the compound and sets it out for the old man to see from his window. Confused and chastened by what he sees, Jilang is paralyzed.

“Jinglan wondered: Could he be lying to cover up his embarrassment? He also thought that he was certainly much different than he used to be. Jinglan glanced around the room: decades had passed, and yet this room was the same as always. The only difference was that it looked much gloomier and more rundown. A crab basket in the corner was covered with thick dust. In the old days, he and Yuanpu had gone crabbing in the mountain streams.”

“Paper Cuts”

A large owl takes up a position in a tree opposite a small rustic home. It kills two young chickens who were just mature enough to begin producing eggs and pecks a piglet to death. But the owl has the most devastating effect on Mrs. Yun, who sees the bird as an omen of evil. Its presence causes her to perseverate on moments of sorrow and joy in her marriage. She and her husband came from the city, where he worked as a coalman hauling carts of coal to local customers. He worked constantly, often to the point of collapse. The couple gave birth to four children during this period, and every single one of them died. Mrs. Yun wanted to give up, but Mr. Yun argued that the city was too contaminated and had poisoned the children, urging his wife to move to the country. Not long after changing their residence and lifestyle, they give birth to a healthy daughter. She matures into an artist who specializes in papercuts, producing increasingly elaborate cuttings, including centipedes, golden ants, and green dragons. Eventually, she announces that she is leaving home to practice her art with a group of like-minded women. In many respects, the tale may be about the pain of the loss of children and the pain of having to let a child leave home. But as in so many of Can’s tales, the narrative is secondary to the welter of symbolic, nightmarish, and enigmatic experiences, hallucinations, or half-remembered dreams that the author offers up to the reader as relevant data crucial to understanding the character. The fever dream and the anecdote are of equal value to Can as she brings Mr. and Mrs. Yun and their daughter Wummei to life. So it is that the owl attacks Mrs. Yun in a frenzy of whips, knocking her unconscious until a handsome man from her past, a tire-repairman arrives, transports her deep into the marsh were they embrace in its waters; a wall collapses and an owlet emerges from the rubble, only to be consumed by its parent; the marsh becomes a place for plotting revolution or exterminating revolutionaries, and the daughter’s creations march throughout her empty room in the darkness.

“Sure enough, that night the chickens and dogs were all in an uproar. The next morning, two chickens were missing. At the gate were chicken feathers and traces of blood. Mrs. Yun thought, was it the owl? Why did she think it was a man-eating beast?”