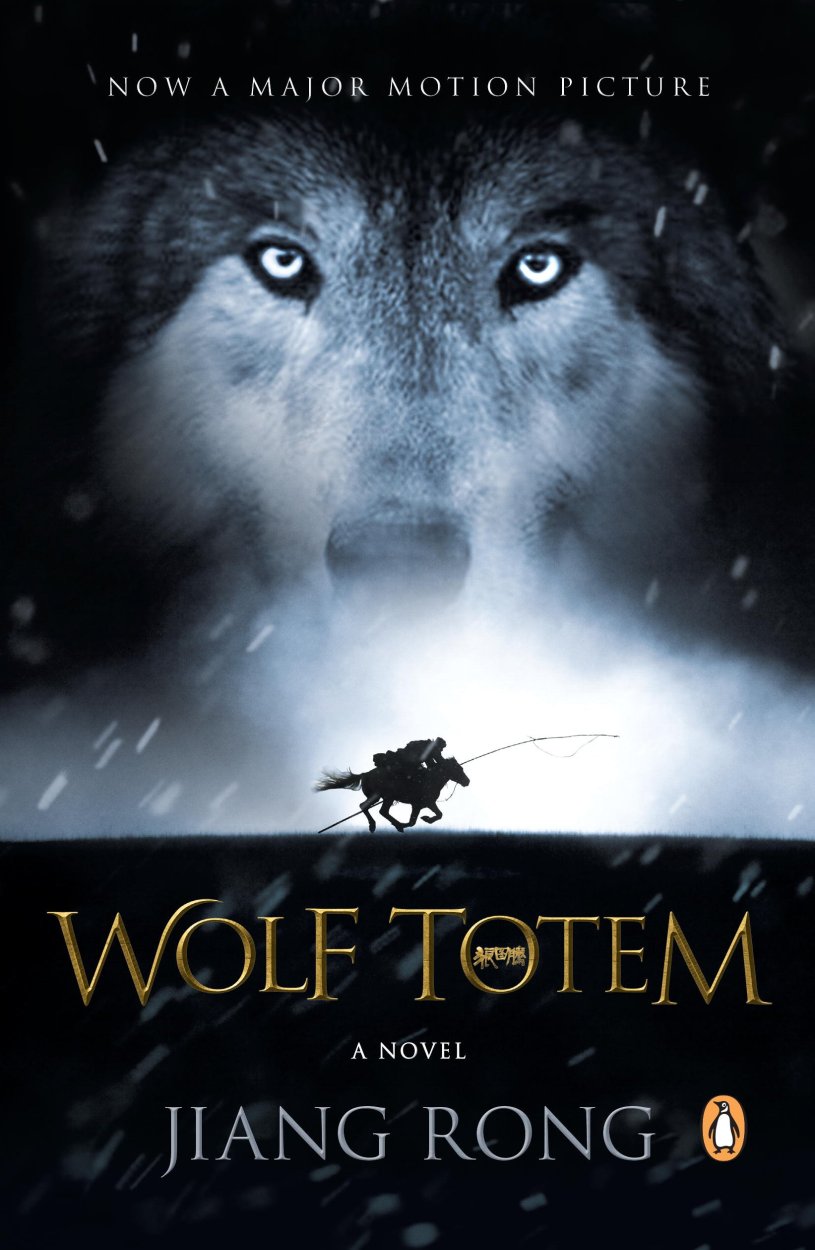

Wolf Totem, By Jiang Rong (real name Lu Jiamin)

By Jiang Rong (real name Lu Jiamin) (m.)

Translated by Howard Goldblatt

(2004, translated 2008)

Penguin Random House

(Memoir, Ecological, Political, and Social Commentary)

The novel is inspired by the author’s experience during the Cultural Revolution. After his father was branded a Capitalist Roader, the narrator, Chen Zhen, a twenty-eight-year-old student from Beijing is “sent down” to be re-educated in Olonbalog in Inner Mongolia. He and one-hundred other Chinese students work in agrarian production teams made up of “sent down youth,” Chinese soldiers and Party administrators. Though he is being trained as a grassland shepherd, Chen Zhen quickly becomes emotionally and intellectually enraptured with the Mongolian wolves. His deep regard for the animals as well as his passion to learn everything he can about their behavior leads him to Bilgee, a renowned grassland elder. Bilgee, in his sixties, has witnessed the degradation of the grasslands as modern Mongols have shifted away from traditional methods of managing the grasslands. Worse, the Communist Chinese, who have a starving population at home, are exploiting the Olonbalog lands, hoping to turn the fragile grassland into an agrarian breadbasket. Bilgee, whom the young Mongols increasingly regard as a relic and by the Chinese as a dangerous adherent to the “Four Olds” responds to Chen Zhen’s enthusiasm for the wolves by adopting him and teaching him the traditions of the grassland. As he spends more time in Olonbalog, Chen Zhen and his Chinese peers grow to admire and emulate the Mongol herders. They are impressed by the wisdom of the herders and their approach to worshipping and protecting the balance of life on the grasslands. The more they are exposed to the strong and courageous Mongols, the more it seems to them that the nomadic lifestyle has created a superior type of being. Reflecting on their own experience of being raised in an agrarian society, they find themselves weak and fearful. As they study Chinese and Mongol history, they struggle to understand how throughout history, small bands of decentralized Mongol tribes conquered Chinese armies that possessed both superior numbers and technology. According to Old Bilgee, the solution is simple: the grassland and the grassland wolf created Genghis Khan and the Mongol armies. Working against and with grassland wolves, the Mongol people grew strong and fearless; more importantly, they learned complex and ingenious battle strategies from observing and warring with the wolves. Again and again, the narrator extols the nomad spirit and wisdom, identifying the people as heroic wolves while lamenting that the agrarian society of the Han Chinese can only produce people who are no better than sheep. In spite of—or because of—this critical refrain, Wolf Totem remains an extremely popular novel in China. Another key theme of the novel is ecology. The Chinese look at the grasslands with greedy eyes, hoping to turn it into croplands. A bullheaded Communist leader named Bao wages an aggressive campaign to wipe out the Olonbalog wolf population. But Bilgee points out that the only way for the Mongols and the grasslands to survive is to allow the wolves to retain their role as managers of the land. From Bilgee’s perspective, there are two lives on the grasslands: Little Life and Big Life. Humans, domestic and wild animals and crops are Little Life. The grasslands are the Big Life. Failure to properly protect the Big Life will lead to disaster for the Little Life. According to Bilgee, wolves must be allowed to live and flourish on the grasslands. They keep down the population of Mongolian gazelles, sheep, squirrels, and marmots which would otherwise quickly overgraze the area and turn the green land into a desert. The Chinese can only see the wolves as a menace and aggressively wage Class Warfare against the Mongolian “Olds” and the wolves. A caveat: sociologists and experts in the grassland traditions contest several of the author’s fundamental claims.

“Chen exhaled nervously as he turned to look at the old man, who was watching the wolf encirclement through the other telescope. ‘You’re going to need more courage than that,’ Bilgee said softly. ‘You’re like a sheep. A fear of wolves is in your Chinese bones. That’s the only explanation for why you people have never won a fight out here.’ Getting no response, he leaned over and whispered, ‘Get a grip on yourself. If they spot any movement from us, we’ll be in real trouble.’ Chen nodded and scooped up a handful of snow, which he squeezed into a ball of ice. The herd of Mongolian gazelles was grazing on a nearby slope, unaware of the wolf pack, which was tightening the noose, drawing closer to the men’s snow cave. Not daring to move, Chen felt frozen in place, like an ice sculpture. This was Chen’s second encounter with a wolf pack since coming to the grassland. A palpitating fear from his first encounter coursed through his veins.”