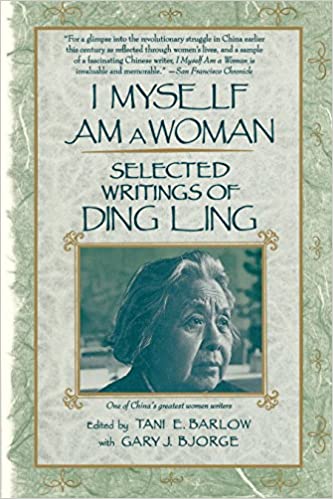

I Myself am a Woman: Selected Writings of Ding Ling, by Ding Ling

Edited by Tani E. Barlow and Gary G. Bjorge

(1990)

Beacon Press

This collection includes an extensive review of Ding Ling’s life, influences, and politics before and after the Cultural Revolution, as well as her impact on Chinese literature. Writings include a novella, excerpts from an unfinished novel, short stories, and “Thoughts on March 8,” her 1942 essay challenging the Communist Party’s position on women, for which she was repeatedly required to perform exhaustive self-criticisms. An ardent Maoist, she and her husband, the writer Ye Hepin, were arrested in Shanghai by the Koumintang, who put Ye Hepin on trial and executed him. The Kuomintang put Ding Ling under house arrest in 1933, but she managed to escape in 1936 to Yan’an, where she became very active in the literature and politics of Mao’s Communist Party. Despite her enthusiastic commitment to the cause, she was denounced as a Rightist in 1956 and spent five years in jail during the Cultural Revolution, after which she was sentenced to twelve years of manual labor on a farm. She was “rehabilitated” in 1972 and is considered one of the exemplary writers of “socialist realism.” Note: she and her husband were closely associated with Shen Congwen, author of Border Town.

“Miss Sophia’s Diary” (1927)

As with many of Ding’s early writings, the protagonist has a western name and influences from European literature abound, including plot elements and even quotations from Madame Bovary and La Dame aux Camelias The narrator is a college-age woman living in university dormitories but unable to attend classes due to frequent hospitalizations for tuberculosis. She seems at war with her woman’s body. It is a vessel of disease yet also prone to uncontrollable sexual desires which society prevents her from satisfying. She masturbates, indulges in wild fantasies, flirts recklessly with a tall foreigner who is frank about his marital infidelities and his affection for brothels, and spends her spare time stringing along and humiliating a man who follows her like a whimpering pup. She alludes to a homosexual relationship with one of her schoolgirl friends, someone who is now deceased, having committed suicide after her marriage to a man When she ultimately “acts” and sleeps with the lothario, she feels a brief moment of mastery before realizing she’s allowed herself to be taken advantage of by a shallow, unintelligent husk of a man. With Miss Sophia, Ding reveals in the frankest of languages the complex world of the modern Chinese woman, exposing both what is human and monstrous about being female. The tale also directly alludes to the May Fourth movement, so it is easy to see the piece as a study of women for whom a new political freedom and identity offers new opportunities and challenges while still acknowledging that they remain confined by inexorable familial and social constructs.

“I teased him mercilessly until he burst into tears. That cheered me up, so I said, ‘Please, please! Spare the tears. Don’t imagine your sister is so feminine and weak like other women that I can’t resist a tear… If you still want to cry, return home and do it. I’m disgusted whenever I see tears…’ … He just curled up in the corner of the chair, as tears from who knows where streamed openly and soundlessly down his face. While this pleased me, I was still a little ashamed of myself. So I caressed his hair in a sisterly way and told him to go wash his face. He smiled through his tears (54).

“A Woman and a Man” (1928)

One of the more interesting elements of this short “romance” is that the central players are Chinese who, in their efforts to enter the modern age, have fundamentally sacrificed their Chinese identities. The woman, like Sophia in “Miss Sophia’s Diary,” has adopted a western name: Wendy. She is a fan of western literature and western movies as well. She views herself as Madame Bovary or La Dame aux Camelias, or some version of Nora from A Doll’s House, and she studies the seductive mannerisms of Greta Garbo. In flight from her very nature and rewriting herself as a patent, tissue-paper-thin fraud, she collides romantically with her male counterpart, a Chinese man who studied in Japan and adopted a Japanese name: Ouwai Ou. The two spar erotically though their relationship never catches fire. As it happens, Ouwai has adopted the tastes of the Japanese: he prefers to express his sexual desire with a Chinese prostitute with bound feet.

“Now she was only blindly running, seemingly in joy as well as fear, with no sense of order, even leaping as she hastened toward the given place. There she would do battle with someone. She wanted her opponent to capitulate, and, just like a prisoner of war, to present her his heart. Once she had accepted it, she could just as well cast it aside as keep it for a time, just so long as it belonged to her. (93)

“Yecao” (1929)

Unlike the young, feckless, Europeanized women of “Miss Sophia’s Diary” and “A Woman and a Man,” Yecao, a twenty-four, seems to have weathered the storms of youthful desire and emerged as a centered and mature woman. She is stable, undisturbed by romantic distractions, and professional. She is also a writer and journalist, which may suggest that she is in some respect Ding Ling herself. There is evidence that she was once overwhelmed by her passions, but when she looks upon rhythm now it seems there is a barrier between her present and past selves. Ding describes a brief encounter between Yecao and an admirer, Xanxia. The atmosphere and the location are romantic enough, and Xanxia believes that he is performing precisely as an avid lover should, but Yecao finds he does not excite her like the lovers of her youth, and so as he earnestly woos her, she thinks about her writing.

“Yecao, a young woman of twenty-four, wearing a gray lined dress appropriate to a middle-aged woman, had shut herself up in a small room alone, worrying over the characters in her novel. She had forgotten spring. In the novel that she was imagining, however, there was a spring day, filled with ecstatic and impassioned love, raging like fire.” (105)

“Shanghai, Spring 1930” (1930)

Ding again studies two different types of modern Chinese women. “Mary” is another westernized Chinese woman. She is highly social, fashionable, sexually active, and self-absorbed. She is attracted to the masculinity of a passionate political activist and she sees his commitment to his cause as a personal affront to her beauty. If left to her own desires, she imagines she will easily peel him away from his crucial leadership role in the Party or simply embarrass him to the point that he will be cashiered. Meilin is Mary’s counterpart. She is very much the traditional wife to Zibin, a writer who first excited her with his novels and who now seems to be drifting in a sea of indecision. As Zibin becomes more irascible and controlling, Meilin begins to desire to expand her knowledge and her world. Zibin would confine her, but Meilin begins to act on her desires. She begins to read more, follows the news, and attends meetings and parties where Chinese interests are discussed. In time, she becomes politically active, devoting less time to her private relationship than to the public cause of a new China.

“After lunch she began to make herself up very carefully. She expected that the people at the meeting would all be quite ragged, even more pitiful than Wang Wei. She had heard that these people were all very poor. She did not want to be arrogant or show off, but she wanted to shock them with her beauty. She wanted to disturb the minds of these revolutionaries.” (157)

“Net of Law” (1929)

“Net of Law” is a study of crime among poor factory workers in Hankou. The work is strongly influenced by Marxist Theory: rather than focus on a character’s moral failing, her characters come to realize that their behaviors are the results of pressures exerted by exploitative factory owners and cruel market forces. We are introduced to a man who abuses his wife. She suffers passively, and although Ding does not portray her abuse positively, she makes a case that his drunken despair and cruel abuse are the perhaps inevitable result of a system of economic exploitation that dehumanizes workers. Powerless to stand for themselves, they act out against those with even less power: women. The inciting incident in the story is a woman’s miscarriage. Her husband, Gu Meiquan, wishes to stay at home to monitor his wife’s recovery in the immediate aftermath of her trauma and asks a friend to relay the request to his factory foreman. The friend fails to speak to the supervisor and the next day, Gu Meiquan is fired and cheated out of a significant portion of his pay. When he discovers his friend’s cousin is hired by the same factory, he comes to believe that he was betrayed and begins to make plans to avenge himself. He commits a fantastically gory crime and is caught and imprisoned. An investigation and trial are convened, but Ding makes it very clear that justice is not served.

“The world is changing more every day. It’s even worse than the time of the Taipings. It’s certainly going to get even worse. It’ll have to before things can get better. These poor people are nearly starving to death. How can they not rise up?If I were younger–if you don’t mind a little joke–I also would be rebellious.” (178)

“Mother” (1932-1933)

Mother is an unfinished novel, selections from which have been published in this anthology. The work is of interest to biographers of Ding Ling, as it is a thinly disguised tribute to her mother. Ding even names the heroine Manzhen, after Yu Manzhen, her mother. The sections excerpted here feature the efforts of an upper-class widow to stabilize the economic and social status of her family and reinvent herself as a modern Chinese woman. After her husband’s death, Manzhen is left to raise her two children and manage a shrinking estate, one that she must soon put up for sale. Nevertheless, she does not allow herself to disappear into the role of traditional Confucian widowhood. She puts servants in charge of her children and though in her thirties and the oldest in her circle, she enters a women’s academy. She expands her understanding of world events and politics in particular, expressing an increasingly intense enthusiasm for Chinese nationalism. She takes on leadership roles and encourages the women in her social circle to swear an oath to the revolution and to their eternal sisterhood. And, she also begins the process of unbinding her bound feet, a painful ordeal that allows her to march in protests and travel. Though there are frequent references to Manzhen’s reliance on leaving her children in the care of others, Ding portrays her mother with pride and admiration. Manzhen shines as a model of a new type of politically active woman and mother, one fit to join in leading the nation forward.

”Before I didn’t understand anything. Before, I heard of the Gengzi incident, but I never paid any attention to it before. So long as the soldiers didn’t come along and fight right in my face, it had nothing to do with me. It’s only now that I know a little about the world outside that I think about such affairs and get angry.” (245)

“Affair in East Village” (1936)

Ding takes the point of view of peasant farmers working under an exploitative landlord. The first “affair” is the relationship between two pure lovers, idealized representations of Chinese stock. Delu’s parents purchased Qiqi to serve as a laborer on the family farm as the eventual bride for their son. As shocking as this may seem for us, the arrangement was common. Lest we judge the parents too harshly, Delu and Qiqi turn out to be perfectly matched. Their attractions and love for one another grow organically, and unbeknownst to Delu’s parents, the two consummate their relationship at fifteen, prior to their scheduled marriage. Nevertheless, Ding does not judge them, portraying them as innocent as Adam and Eve. The snake in the garden is old Zhao, the landlord who controls the entire countryside with an army of paid enforcers. He demands that Qiqi come to work for him as a housemaid. As Delu anticipates, Zhao rapes the young girl. This news coincides with or precipitates a long-brewing revolt of workers, who flock to Zhao’s estate and administer mob justice.

“Furthermore, what Delu correctly guessed, and what Qiqi constantly dreaded, finally did occur. It was not something Qiqi could be blamed for. She was only a fifteen-year-old girl, she had no strength to resist, and she was shut up inside a cage.” (269)

“New Faith” (1939)

This is a shocking piece for many reasons. On the face of it, it appears to be undiluted agitprop. A village hears of the approach of marauding Japanese troops. Those who can, flee, returning several days later to search for family members who were unable to escape. They find evidence of unspeakable cruelty and the mutilated corpses of women and children. They also find the elderly, one who is near death. They nurse her back to health, and she tells of witnessing atrocities and being forced at gunpoint to lie with a Japanese. “Ma” can not stop telling her story. She goes from village to village publicly reliving her trauma and demanding revenge against “the Japs.” The matriarch sees the assault as an assault on her as an individual woman and places the burden of vengeance on her extended family. But when female cadres from outside the village happen to witness her retelling of the crimes committed against her and her family, they quickly realize that her tale of brutality and her unquenchable desire for revenge might electrify the populace and accelerate the resistance against the Japanese. They take “Ma” on tour, literally amplifying her by giving her a microphone and a stage. Soon she is addressing multitudes, inspiring throngs to avenge not only her suffering, but the suffering of all Chinese women.

“‘Ma.’ He directed each deliberate syllable toward the wooden face. ‘Ma! You can die in peace now. Your son will give his life to revenge you. I live on now only for Jap blood! I’ll give my life for you, this village, Shanxi Province, the nation of China! I want Japanese blood so I can cleanse and fertilize our land.” (289)

“When I Was in Xia Village”

Easily one of the most extraordinary short stories by a Chinese writer. The narrator is a journalist who is sent to a backwater for a short period; the unspoken reason behind her “assignment” is that she may have published something that may have been “hot” politically. Her travel companion is another journalist known for her flat affect and uninspired writing. Both women are transformed by their experience in Xia, where they become observers to the plight of a villager named Zhenzhen. Her father was negotiating with a thirty-year-old owner of a rice store from nearby Xilu who wanted to marry Zhenzhen, who was in her mid-teens. Zhenzhen was horrified by her father’s plan and fled to the Catholic church. She hoped to become a nun, and she also imagined the church would protect her from the advancing Japanese. When the Japanese took the village, they captured Zhenzhen and enslaved her as a “comfort woman.” She was eventually “married” by a Japanese officer, and managed to escape back to Xia village to meet with her parents. She also met with resistance fighters who urged her to become an agent, feeding the Chinese accurate information about Japanese troop strength and movement and feeding false information to the Japanese. Her work is spectacularly effective, but she is being “retired” so that she can be treated for a disease she contracted while with the Japanese. The woman is a hero in every way, but the people of her village scorn her as a shameless whore and a collaborator. The women are especially cruel to her, as is her own mother. A childhood sweetheart waits in the wings, determined to make her his wife, but she will not have him. Stoic, Zhenzhen confides to the narrator that her dream is to leave the village and her past far behind, cure herself of her disease, and begin life again as a new person. If there were any doubt as to what Ding thinks of her protagonist, “Zhenzhen” means “doubly true” or “doubly pure.”

“The youth were very good to her. Naturally, they were all activists. People like the owner of the general store, always gave us cold, steely stares. They disliked and despised Zhenzhen. They even treated me as someone not of their kind. This was especially true of the women, who, all because of Zhenzhen, became extremely self-righteous, perceiving themselves as saintly and pure. They were proud about never having been raped.” (309)

“Thoughts on March 8” (1941)

A critical read for anyone interested in the intersection between feminism and Maoist philosophy. Ding composed the piece on International Women’s Day in 1941, but realizing the provocativeness of the piece, she held off publishing it for a year. In it, she called out her male colleagues for their failure to accept female Party members as equals. If women held up half the sky, why were they facing consistent bias, even in Yan’an? Mao condemned the piece and she was forced to recant her claims, though many claim that Ding’s public challenge caused a significant shift in Mao’s thoughts on women, a shift that made Party membership more appealing to women and lead to the greater success of the movement.

“In general there are three conditions to pay attention to when getting married: (1) political purity; (2) both parties should be more or less the same age and comparable in looks; (3) mutual help. Even though everyone is said to fulfill these conditions–as for point 1, there are no open traitors in Yan’an; as for point 3, you can call anything “mutual help,” including darning socks, patching shoes, and even feminine comfort…and yet the pretext for divorce is inevitably the wife’s political backwardness.” (318)

“People Who Will Live Forever in My Heart: Remembering Chen Man”

The last two pieces in the anthology are hagiographic in tone. Here she describes an encounter with a simple woman of the country who has become so imbued with the spirit of Mao and revolution that she reenergized the author’s faith in the Chinese People and the glorious future of communism. The narrator is an educated journalist who has access to the centers of power in Ya’nan. She has studied Mao’s writings and all manner of political, philosophical, and economic works from Russia. Yet her encounter with the simple speech and profound faith of Chen Man raise the author to a higher understanding of the glory and power of Maoism. In Chen Man and Du Wanxiang, Ding is, to some extent, creating a female version of the legendary Lei Feng, an exemplar of all that is good about the Chinese people.

“We have Chairman Mao, so we don’t have to be scared of anybody. All the poor people in the world belong to one family, united in spirit and all of one mind…We must all thank Chairman Mao from the bottom of our hearts; we must turn ourselves over, and be our own masters to make Chairman Mao happy.” (324)

“Du Wanxiang” (1978)

The last story in the collection is almost absurdly propagandistic were it not for a twist Ding adds at the end, a strategy that rescues “Du Wanxiang” from banal hero worship to a reminder of the unique power of the female experience in imbuing a cadre with the voice that is most honest, most lacking in pretension, and most effective. Throughout most of the story, Ding portrays Du as a demure everywoman who invariable sacrifices her own needs to help individual or production teams achieve their goals. She is more than willing to suffer personal setbacks and indignities in order to keep the peace and to maintain the advance of the collective. Occasionally, characters take her aside to explain to her that they see what she is doing and respect her political sensibilities. Unschooled, unattractive, and introverted, she boldly speaks out on behalf of her unit in a simple but thrillingly patriotic manner, a performance that launches her into more and more significant leadership positions. Eventually, younger cadres realize that this simple peasant has the power and pure enthusiasm to inspire the masses. They surround her with writers who add authority to her speeches by quoting the great heroes of the movement, articles on increased agricultural production and adulatory newspaper articles. In the end, the heroine decides to abandon these props. Instead, she goes on stage to tell her own story as a woman, a presentation that wins the hearts and minds of thousands of new Party members. Though Ding was born into the gentry and went to college, some critics believe Du Wanxiang is a stand-in for the author, a person who worked steadily at revolution and invented a meaningful way of promulgating its lofty goals through a new type of literature.

“The text of this speech was excellent. It drew on newspaper editorials. It evidenced real appreciation of Chairman Mao’s works. It relied heavily on the experience of outstanding revolutionary figures. Yet, Du Wanxiang thought, these beautiful words are not what I speak.” (352)