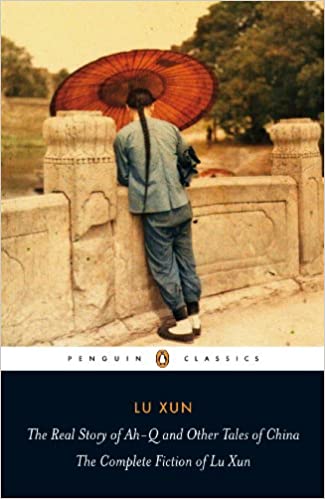

The Real Story of Ah-Q and Other Tales of China: The Collected Fiction of Lu Xun, by Lu Xun

Translated by Julia Lovell

Penguin Classic

(2010)

(Short Story Collection)

Lu Xun reigns over all Chinese writers of the 20th century, not only because of the genius of his work but also because he bore the imprimatur of Mao Ze Dong. He wrote thirty-seven short stories in his brief career. Lu Xun translated several of Nikolai Gogol’s works into Chinese. There is no doubt that Gogol’s short story “Diary of a Madman” and the novel Dead Souls influenced Lu Xun. Ivan Goncharov’s Oblomov also had an impact on the writer. He remained interested in Russian literature throughout his life and even hosted the Russian poet Vasili Ereshenko in Shanghai. But make no mistake, Lu Xun was and continues to be the voice of China.

The collection begins with Mr. Lu’s first short story, the memoir “Nostalgia,” followed by a group of short stories published under the title of Outcry or A Call to Arms. Reading the “Preface” to Outcry is essential to understanding Lu Xun’s mission. A shorter collection, Hesitation or Wanderings, follows, as well as his satirical versions of mythological and focal tales, Old Tales Retold.

“Nostalgia”

Mr. Lu’s “Nostalgia” is a memoir in miniature in which he first broaches many of the themes he explores in his writing. He takes the reader back to his childhood and introduces us to his old family servant Wang and amah Li, as well as the bane of his existence, his teacher, whom he refers to as “Bald” or “Old Bald.” Young Lu likes nothing more than to listen to the evening pipe-fueled conversations of the family servants. By day, he is tormented by the Confucian teachings of Mr. Bald. Bald’s teaching style seems built around authoritarianism, condescension, and physical punishment. Lu is overjoyed then when he notices the embarrassing level of deference Mr. Bald demonstrates toward a high-status, greedy neighbor who is as intellectually challenged as a brick, an oaf who, in conversation about rice, can’t distinguish between “the glutinous and non-glutinous varieties.” One day this Yaozong carries a rumor to their door: the “long hairs” are coming. The servant Wang objects: it has been forty years since the Taiping rebellion ended. Even the teacher suggests that perhaps Yaozong is mistaken. Perhaps they were other bandits? But when Yaozong insists that he heard the rumor from San, another high-status neighbor, young Lu observes his teacher quietly retreat to his room, emerge with packed bags, and quickly excuse himself, claiming he is off to visit his home. The story introduces the continuing influence of the Taiping rebellion on Lu, as well as Lu’s criticism and rejection of Confucian pedagogy.

“And there I found myself, the next day, suffering another lecture on The Analects, my teacher’s head swinging from side to side as he glossed each and every word. He was so shortsighted he was almost kissing the book, as if he wanted to gobble it up. I was always being accused of not looking after my books: of leaving them in a state of disastrous disrepair less than half a chapter in. Well, they didn’t stand a chance with my snorting, dribbling teacher – their chief instrument of destruction – blurring and mangling the pages far more efficiently than I ever could.” (2)

“Preface” to the collection Outcry

Lu combines a brief overview of his early life, his family’s misfortunes, his decision to pursue a modern Western-style education in Japan, and a vivid description of his early struggles as a young writer. As a boy, Lu found himself shifting between the pawnshop and the pharmacy. The doctor treating his father’s illness practiced traditional Chinese medicine; his prescriptions required fresher and more exotic and expensive ingredients. In the end, they failed: Lu’s father died at thirty-five. Against his family’s wishes, Lu decided to study Western medicine at the free Nanjing Naval College. He withdrew when he learned that on graduation he would be required to work in the engine rooms on ships of the Chinese navy. Before and after this adventure, he took the Chinese exams for Civil Service, failing to earn an advantageous grade both times. In 1902 he graduated from the School of Mines and Railways. He then spent several frustrating years attempting to spark a revolution in Chinese literature. Reading the “Preface” is essential to understand the inspiration for his mission as a writer: intense nationalism, a loathing for the Chinese reverence for primitive medicine and rigid Confucian thinking, and a sense that China must create a powerful new sense of morality to guide both the individual and the collective.

“Though physiology was not on the curriculum, we caught glimpses – as wood-block prints – of works such as A New Treatise on the Human Body and Essays on Chemistry and Hygiene. When I compared what I remembered of the diagnoses and prescriptions of our traditional doctors with what I had come to learn of modern medicine, it gradually dawned on me that practitioners of Chinese medicine are – intentionally or otherwise – conmen.” (15)

“Diary of a Madman”

The conceit is multilayered. The narrator claims that he is visiting two brothers he knew from long ago. He has heard that one of them is mentally ill. On his arrival, the healthy brother reports that the “madman” has recovered, but he offers the narrator an opportunity to study the nature of his brother’s illness by allowing him to read the “madman’s diary.” The narrator then reports that he read the diary in its entirety, amended it, and is going to share with the audience the most significant and illustrative excerpts from it. Incidentally, the healthy brother describes his brother’s affliction as a kind of “persecution complex.” Indeed, the ill brother reports that he has lived his life as if in a dream, only to wake one day to realize that the people in the village he inhabits, “Wolf Cub Village,” have all turned against him. The madman begins to see evidence of animal, dog-like qualities in his neighbors. He overhears a mother threatening to eat her child and learns of a rumor that a friend has been killed and his liver eaten by ferocious villagers. The madman believes he is in danger of being eaten due to his “Records of the Past;” he also acknowledges that such cannibalism is a historical fact and not unheard of in times of famine. The nightmare soon devolves into chaos. Are people in the village being paid in human flesh? Does the soup he is eating contain human flesh? The short story addresses many issues, but the central imagery of cannibalism is likely inspired by The Twenty-Four Filial Exemplars, a text of Confucianism, which celebrates the sacrifice of “filial slices:” sons were encouraged to slice off flesh from their own bodies to add to healing broths to be served to sick parents.

“Another of their ingenious devices: to discredit me as insane. The plot was too well laid; they would never change. And when the moment arrived for me to be eaten, there would be not a murmur of opposition, only sympathy for my butchers. Death by character assassination – a method tried and tested by the farmers of Wolf Cub Village.” (29)

“Kong Yiji”

One of the recurring characters in Chinese literature is the frustrated scholar. Invariably, this involves a young man from a poor or less-than-influential family whose parents set him on the scholar’s path in the hopes that he will one day pass the Imperial examination and qualify for a career as a bureaucratic civil servant. Stories abound of characters who take and retake the exam over many years. Sometimes a worthy candidate overcomes all obstacles and succeeds—“Kong Yiji” is not one of those stories. The narrator is a young boy excited to be working amongst men in a tavern. Kong Yiji appears one day. His scholar’s robe is threadbare and his beard is wild. He is old, unclean, gangly, and eccentric. The regulars mock him without mercy, but the tavern owner supplies the old man with drinks and the failed scholar is kind to the boy. But Kong Yiji may have descended to theft; after a long hiatus from the tavern, he crawls in begging for a bowl of wine, both of his legs broken. There is a film of the short story on YouTube: “Kong Yiji” Video. If you are interested, there are also Chinese operas of Kong Yiji’s story.

“Lunchtime or evening, when they got off work, the town’s labourers would drift in, each with their four coppers ready to buy a bowl of warmed wine (this was twenty years ago, remember; now it would cost them ten), then drink it at the bar, taking their ease… But such extravagance was generally beyond the means of short-jacketed manual labourers. Only those dressed in the long scholar’s gowns that distinguished those who worked with their heads from those who worked with their hands made for a more sedate, inner room, to enjoy their wine and food sitting down.”

(32)

“Medicine”

An old man, Shuan, rises in the night, leaving his house clutching a piece of silver. In the darkness, he passes a great many soldiers on the march. When he reaches his goal he exchanges the coin for a bright red bread roll. His wife, Hua Dama, cooks the roll and feeds it to her ailing son, who is suffering from consumption. Mr. Kang arrives. It was he who gave the family the money to obtain the folk cure, and it is he who reveals to the audience its horrifying ingredient. What will happen to the son? How was the ingredient obtained? Mr. Lu presents a nightmarish, almost hallucinatory tale of horror focused on his contempt for traditional Chinese medicine and superstitions.

“By the time Shuan returned home, the main room at the tea-house had been cleaned and tidied, its rows of tables polished to an almost slippery shine. No customers, only his son, sitting eating at one of the inner tables, fat beads of sweat rolling off his forehead, thick jacket stuck to his spine, the hunched ridges of his shoulder blades almost joined in an inverted V. A frown furrowed Shuan’s forehead. His wife rushed out from behind the cooking range, wide-eyed, a faint tremble to her lips.” (39)

“Tomorrow”

As with “Medicine,” Lu turns his focus again on those who profit from illness and death. This time he tells the story of a young widow, Mrs. Shan, and her struggle to make a home for her and her young son, Bao’er. The boy is sickly, suffering from a breathing disorder, perhaps asthma. As his condition worsens, she takes her savings to Dr. Ho, who observes the boy, offers a nonsensical diagnosis and prescribes a costly nostrum.

As the widow’s tragedy unfolds, we see the people of the village of Luzhen exploit her at every opportunity, pretending to support the poor woman while filling their wallets and stomachs. As in so many of his stories, Lu criticizes the immorality and greed of the Chinese people and weeps for the truly noble souls who live for love.

“Even though it was still early, the doctor already had four patients waiting for him. Four silver dollars bought Bao’er fifth place in the queue. Ho Xiaoxian uncurled two fingers – both nails a generous four inches long – and felt his pulse. Surely this man can save Bao’er, marveled Mrs. Shan to herself. ‘What’s wrong with Bao’er, doctor?’ she asked nervously. ‘His stomach’s blocked.’ ‘Not serious, is it? He –’ ‘Take two of these.’ ‘He can’t breathe properly; his nostrils shake every time he takes a breath.’ ‘That’s because his Fire is vanquishing his Metal.’” (47)

“A Minor Incident”

A two-page vignette that packs a powerful moral and political statement. Set in 1917 in a windy, dusty Beijing, a fur-coat-wearing gentleman hires a rickshaw to take him across town. Almost immediately, the rickshaw collides with an elderly woman. What happens next, as well as the behavior of the rickshaw driver, affects the narrator so deeply that he realizes that none of the great political achievements or military victories of the new Republic can equal the hopefulness he feels about his and China’s future at this precise instant.

“Without a moment of hesitation, the man now began to inch her forward, keeping hold of her arm. Startled, I noticed a police station – its exterior deserted after the morning’s ferocious wind – a little way ahead. He was helping her on towards its main door. In that brief moment, a curious sensation overtook me: his back, filthy with dust, suddenly seemed to loom taller, broader with every step he took, until I had to crick my neck back to view him in his entirety.” (54)

“Hair”

This brief story allows us to eavesdrop on an increasingly animated conversation between two men who meet on “double ten day”—October 10th—the anniversary of Revolution Day, October 10, 1911. The speaker’s patriotism is muted due to his frustration with his nation’s long linkage between politics and hair. He claims that since the 16th and 17th-century rule of the Manchus, the Chinese “fight for revolution” was really a fight to avoid having to wear the sign of humiliation: the Han resented that they were forced to adopt the Manchu style, shaving the front half of their heads and wearing a long braid down their backs. To shave the queue off was seen as an act of rebellion: violators of the hair code would be decapitated. “Mr. N” then points out that if a man grew his hair out in the mid-nineteenth century during the Taiping rebellion, he would be murdered by government troops or the Taiping rebels, who were nationalists and Christian religious zealots who believed their leader was the brother of Jesus Christ. “Mr. N” rails about the clash between ancient practices, obedience to a central authority, and the modern movement to adopt European-style clothing and hairstyles, all the while asking the perennial question: what does it mean to be Chinese?

“Within a few years, though, the family fortunes had gone to the wall. If I didn’t find myself a job, I was going to starve, so I came back. First thing I did when I got to Shanghai was buy myself a false queue – two dollars was the going rate at the time – then went on home. My mother somehow managed to keep her mouth shut about it, but the first thing anyone else I met did was to examine this new appendage of mine. And the minute they worked out it was false, they’d smirk and start plotting to turn me in to the authorities for immediate decapitation. A relative of mine would have turned me in if he hadn’t been more afraid the Revolution might succeed.”

(57)

“A Passing Storm”

This piece is sometimes translated as “A Storm in a Teacup.” Again, Lu addresses the politics of the queue. In July of 1917, General Zhang Xun entered Beijing with the Northwestern army, declared the return of the Qing Dynasty, and installed the last Emperor, Puyi, on the Dragon Throne. For almost two weeks, men throughout China worried about the consequences of cutting or keeping the queue. Will the new Emperor want a queue or not? And what should happen to those who cut theirs? In “A Passing Storm,” Master Zhao, who is a Qing loyalist, insists that his village rival, Mr. Seven Pounds, will surely be decapitated for cutting off his queue. Mrs. Seven Pounds despairs, cursing her husband for ignoring her pleas to avoid going to Luzhen, where he was attacked by a mob that shaved off his queue. A debate erupts in the backwater bar, The Universal Prosperity Tavern, as uninformed, superstitious, and jealous men threaten one another as if they spoke with the authority of a royal advisor. The panic Zhao maliciously unleashes sparks a melee in the bar as insults and slaps fly and a rice bowl and a six-foot-long smoking pipe come to ruin. How will this comic but potentially deadly battle be resolved?

“‘But where, might I ask, is your queue, Mr. Seven-Pounds? This is no laughing matter. Remember the Taiping Rebellion! If you kept your hair, you lost your head; lose your hair, and the head stayed on…’ As neither Seven-Pounds nor his wife had been to school, the profundity of this historical allusion floated some way over their heads. But they could see that if a man of Mr. Zhao’s wisdom was talking like this, then the situation was serious indeed; beyond salvation, in fact. They fell silent, listening to their death knells clanging in their ears. (65)

“My Old Home”

Lu gives us poignant homecoming, the narrator’s final visit to his hometown after a twenty-year absence. He discovers a dilapidated village, one that he can’t quite match his childhood memories. The narrator confesses that in his current home he barely “scrapes a living,” but he is overwhelmed by the poverty he sees around him. His frail mother and his young nephew, Kong’er, come out to greet him. The youth of the latter sets him to think of the eternal companion of his youth, Runtu. They first met thirty years ago, when the boys were ten and nine, and the narrator’s family was financially comfortable. They had a permanent servant; his son was the loyal and adventurous Runtu. The narrator makes a point of tracking down his old friend, a boy he envied because while he was confined to the home or school, Runtu was out guarding the garden against thieves, fighting off folk demons, or fishing. Their reunion, as well as his surprising conflict with an envious villainess: Mrs. Shan, the renowned former “Bean Curd Beauty,” is a poignant and moving study of class in China.

“Once he had gone out, Mother and I sighed over his situation together: too many children, famine, taxes, soldiers, bandits, officials, corrupt local potentates – they’d all taken their pound of flesh. Anything we didn’t need to take with us, Mother said, we should give him; he could take whatever he wanted.” (77)

“The Real Story of Ah-Q”

Lu Xun originally published this novella serially in 1921 in the Beijing Morning News under the name Ba-Ren or “Crude Fellow.” It was one of the first works of literature written in vernacular after the 1919 May 4th Movement. The affirmation in the title that this is a “real story,” the picaresque nature of the hero’s adventures, the hero’s rejection of reality, as well as Lu’s decision to call the hero by a name that mixes the Western “Q” with Chinese suggest some influence by Cervantes, but make no mistake: Ah-Q is being used a negative example to inspire Chinese to live more moral lives. The “Q” is also a reference to the Chinese braid; Lu Xun quipped that from behind, the average Chinese man looked like a letter “Q.” He also suffers from ringworm; the scars on his face glow bright red when angered or humiliated. Ah-Q is anxious about his lack of familial connections. He frequently tries to associate himself with the wealthy Zhao family, eventually alienating these authoritarians. Ah-Q is notorious for the way he characterizes each embarrassing loss as a great victory, his inflated sense of self-importance, as well as his greed. He lacks self-awareness and cannot begin to see the world through any perspective but his own. When he hears of the goals of the Xinhai or Chinese Revolution of 1911, he applauds its goals but only because he imagines that the political movement will allow him to plunder the wealth of his enemies. Rejected by the rebels, he becomes sullen and bitter. Eventually, Ah-Q is executed for theft. He tries to make his exit from the world a triumph, but he even fails at that. The story remains very influential. These two observations from Wikipedia illustrate that the character remains relevant today:

“In modern Chinese language, the term the ‘Ah Q mentality’ (阿Q精神, ‘Ā Q jīngshén’) is used commonly as a term of mockery to describe someone who chooses not to face up to reality and deceives himself into believing he is successful, or has unjustified beliefs of superiority over others. It describes a narcissistic individual who rationalizes every single actual failure he faces as a psychological triumph (‘spiritual victory’).”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_True_Story_of_Ah_Q#References_in_modern_culture

The term Zhao family (赵家人, Zhàojiārén), a derogatory term for China’s ruling elite and their families, from the character Mr. Zhao, entered contemporary Chinese language. Originally appeared in a wechat article, the term subsequently became an internet meme widely used by dissident netizens, with numerous variations such as 赵国 (Zhaos’ empire, China) and 精赵 (Zhao’s spiritual members, 50 Cent Party). The term was thereafter banned by the Communist Party of China.[9]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_True_Story_of_Ah_Q#Zhao_family

Interestingly, several year 9 students from China have recognized a bit of Ah-Q in a character they study in English class: Holden Caulfield from The Catcher in the Rye!

“In the distance, yet another of Ah-Q’s bêtes noires was now approaching, yet another individual for whom Ah-Q felt the greatest disgust: Mr. Qian’s eldest son. Sometime past, he had gone off to town to enrol in one of the newfangled Academies of Western Learning, then somehow gone off again to Japan. Six months later, he was back, goose-stepping like a foreigner and his queue gone with the fairies. His mother had wept inconsolably, while his wife had tried to commit suicide three times by jumping into the well. Eventually, his mother took to putting it about that ‘wicked people had got him drunk and cut off his queue. Otherwise, he’d have had a top posting by now, but as it is he’ll have to wait till it’s grown back.’ Ah-Q was having none of this, and knew him only as the ‘Fake Foreign Devil’, or ‘Traitor.’”

“Dragon Boat Festival”

Not what you think it is! Dragon boat festival happens on the fifth day of the fifth lunar month and it is traditionally the day when all debts are due. The hero, Fang Xuanchuo, is a lecturer at the College of Supreme Virtue in Beijing. He also supplements his income by moonlighting as a government servant. As with “The Real Story of Ah-Q,” Fang adopts a philosophy of apathy and convenience. Fang consoles himself that under the Republic run by Yuan Shukai, China before the Revolution and after the Revolution are “pretty much the same,” a maxim he repeats to himself throughout his days (124). Early on, he has a moment of self-awareness: “Sometimes, seeing the direction in which his thoughts were turning, he wondered if he had lost the will to fight social oppression – was he hoodwinking himself, to escape unpalatable truths? Had he become what the Confucian sage Mencius termed ‘a man incapable of distinguishing between right and wrong’?” (124). Despite the stirrings of conscience, Fang continues to luxuriate in the sense that nothing can be done and nothing will change. When the university stops paying the faculty, Fang, who had never joined the teacher’s union, is content to let others do the leg work of protesting. Later, when the state refuses to pay government servants, Fang slowly works around to expressing dissatisfaction, but he invents excuses to avoid joining the protests himself. As his financial situation worsens, his wife begins to panic, but the hero continues to justify his inaction. The story is based on actual events: on June 3rd of 1921, ten thousand teachers and students took to the streets of Xinhuamen to demand back pay from the government.

“Fang’s ‘more-or-lessism’ was nothing more than an expression of a new sense of grievance against the world – though not one that he had the least intention of acting on. Whether it was because he was lazy, or just utterly inert – even he didn’t know – Fang Xuanchuo had always considered himself a stoically law-abiding sort of person, the kind that refuses to take part in any kind of public protest. While his own position in the bureaucratic cosmology was not under threat, his minister could accuse him of every neurosis under the sun and still the system wouldn’t hear a whisper of dissent from him. The university could owe him more than six months’ salary, but as long as his income from his government job kept coming, he would keep his head resolutely down.” (125)

“The White Light”

Lu once again returns to the topics of the frustrated scholar and the madman. This time Chen Shicheng, already gray at the temples, searches for his score on the provincial civil service exams. He knows a high score will make him desirable as a future husband and imagines a life with a beautiful bride. He fails to see his name published on the list and returns home, cursing that for the sixteenth year in a row “no single examiner had known a good essay when he saw it.” As he walks along, he fantasizes about the life he might have lived had he passed the examination, and his head begins to swim. He experiences auditory hallucinations and his vision becomes blurry. Once home, he does not eat. Instead, he does what he has done after failing every other exam: he begins to search for a treasure rumored to be hidden underground, a trove buried from a time when his family was successful.

“With the county competition behind him, he could have tried his luck at the provincial level, soaring through the ranks of government… All the best people would try to marry their daughters off to him, worshipping him like a god, regretting their earlier, short-sighted lack of respect… He would get rid of the tenants who had rented rooms in the derelict old family house – though likely as not, they would all have deferentially moved out of their own accord, to make way for him.” (133)

“Cat Among the Rabbits”

Lu appears to be telling a simple story. A family purchases two rabbits, and both adults and children while away their days delighting in their pets’ behaviors. Then, when one of the rabbits becomes pregnant, the story takes a series of unexpected turns. The mother appears to starve her infants of milk. A sole survivor comes up to feed on grass and both parents force it back underground, blocking the exit with mud. A second, larger tunnel appears. The mood of the human family changes. A sister is certain that a large black cat is to blame. The narrator too discovers that he has a murderous loathing for all cats. It should be noted that Lu composed this story while hosting the Russian poet Vasili Ereshenko, who is a central character in the story “A Comedy of Ducks.”

“Well, if I can’t beat the Creator, I might as well join him in his little game of willful destruction. That black cat won’t be stalking up and down that wall forever, I resolved to myself, glancing at the bottle of potassium cyanide in my book cabinet.” (143)

“A Comedy of Ducks”

Written in 1922, this is a barnyard fable set in Beijing. A fascinating detail: the main character is an outsider, the blonde-haired, blind Vasili Ereshenko. The blind Russian poet and musician, has just arrived after a tour of Burma. Reaching for his balalaika, he laments that Beijing is a silent city: he hears no natural sounds at all. His host, a Chinese nationalist, is ashamed to admit that his city is a desert. But after remembering that the frog population emerges after the rainy season, Ereshenko and his host are inspired to introduce tadpoles into a small hand-dug lotus pond. Later, they purchase four ducks, which cause mayhem for the visionary engineers of the sounds of nature. Sweeping agricultural movements, man-made natural disasters, the influence of outsiders, and the danger of good intentions are some of the thoughts we are left to ponder as the blind Russian returns to Siberia.

“Practicing self-sufficiency had always been another of his notions: women, he was often saying, could concentrate on the livestock, while their men worked the land. He was always trying to inveigle friends to grow cabbages in their courtyards, or advising my sister-in-law to keep bees, hens, pigs, cows and camels. In time, and probably in capitulation to Eroshenko, Zuoren’s courtyard became a run-around for chicks – skittering everywhere (on and above ground), pecking at the tender young leaves that carpeted the yard.” (145)

“Village Opera”

The narrator reflects on two instances when he attended a Chinese Opera. The first was in 1912. He was not a fan; the clanging gongs, ramshackle seating, and the flashing, chaotic movement on stage drove him out to the street, where he gasped for breath. In his second experience, probably around 1931, after the Hubei floods, a portly friend invited him to another opera, this time featuring a highly-touted star performer. Once again, the narrator found it impossible to determine what everyone was so excited about and attempted to flee the theater. But then the narrator reads a Japanese critic of Chinese opera who insists that the noise, spectacle, and high-voiced singing is specifically designed to be enjoyed outdoors. The article reminds the narrator that he attended an outdoor opera when he was ten or eleven. He had been away at school and returned to visit his extended family, where he feels strangely like an outsider. Nevertheless, when he and a group of his young relations get permission to paddle a white-roofed boat to watch a torchlit opera, the narrator finds himself transported to another world—especially since he and his young friends are free of adult supervision.

“The moon seemed to have hardly moved – as if we’d been watching the opera for no time at all – and once clear of Zhaozhuang, it beamed down with extraordinary brightness. When I turned to look back at the stage lights, the theatre looked just as it had done on our approach: rising hazily up from the river bank like an enchanted pavilion, enveloped in rosy mist. The music of bamboo flutes caressing our ears, I came to suspect the old woman had finally finished, but was too embarrassed to suggest we go back.” (156)