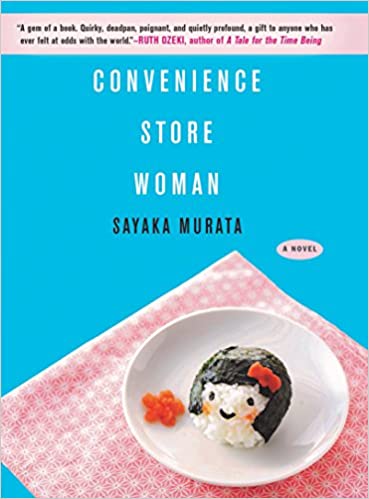

Convenience Store Woman by Murato Sayako

By Murato Sayako (f.)

Translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori

(2016, translated 2018)

Grove Press

(Novel)

Ms. Murato’s narrator is a thirty-six-year-old single woman who has worked for eighteen years as a convenience store clerk. Some readers are eager to diagnose the narrator as someone on the autism spectrum. She lives a highly structured life and embraces the organization, routine, and mission of the store. She has no social contacts outside of the store and has never been in a relationship. Much of her time is spent observing how people talk, dress, and behave, mimicking their speech patterns, subtly adapting her fashions to those she comes into regular contact with, and surreptitiously taking note of shopping bags and exposed clothing labels. But Keiko Furukura’s situation as well as her perception of how she fits into the world is significantly more complex. She knows she is a disappointment to her family. High school girls, immigrants, wives whose husbands are in a bad patch work at convenience stores. But Miss Furukura continues to do the same tasks every single day and never even thinks of applying to be a manager. Graciously, her sister has created a cover story to give Miss Furukura an answer to co-workers who are puzzled and even exasperated by her failure to develop a career, marry, and have a child. Indeed, Furukura finds children repulsive and frequently refers to the people around her as animals. She tries not to think of her life before she began working at Smile Mart, referring to the day she was hired as the moment of her rebirth. She organizes her philosophy around slavish obedience to the convenience store worker’s manual. Everything she has consumed over the course of her employment, food or drink, has come from the convenience store. She is the store and the store is her. She is proud of her intimate relationship with the lights, sounds, and colors of Smile Mart and relishes the opportunity to listen to its needs. As idiosyncratic as she is, she is not alone. The convenience store briefly employs someone at least equally eccentric: a cynical, abusive college drop-out who claims he is working at the store to meet a woman for marriage. He exhibits the violent misogyny of involuntary celibates or the “incel” culture here in the U.S. But he soon reveals a darker secret: his desire to disappear from society, becoming one of Japan’s jouhatsu, the alleged one-hundred-thousand citizens who “evaporate” from Japan each year, leaving no trace. Murata’s book is short, fast-paced, disturbing, and weirdly funny. At times, Miss Furukura seems a victim, sometimes a monster, and at other times simply a modern human enjoying her metamorphosis into the perfect service worker.

“When some of Sugawara’s band members came into the store recently they all dressed and spoke just like her. After Mrs. Izumi came, Sasaki started sounding just like her when she said, ‘Good job, see you tomorrow!’ Once a woman who had gotten on well with Mrs. Izumi at her previous store came to help out, and she dressed so much like Mrs. Izumi I almost mistook the two. And I probably infect others with the way I speak too. Infecting each other like this is how we maintain ourselves as human is what I think.”