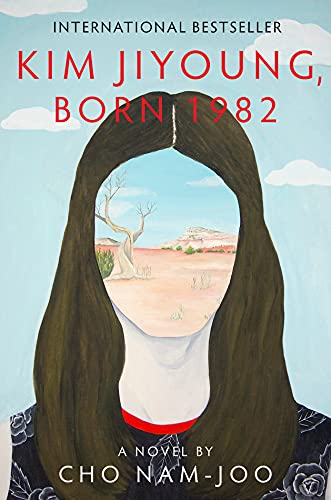

Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982, by Cho Nam-joo

Translated by Jamie Chang

(2016, translated 2019)

Liveright

(Novel)

Cho Nam-joo is reported to have written this novella-length mash-up of fiction and fact after being insulted as a “worm woman” or “roach woman” while attempting to maintain her career and raise a child. Cho introduces her everywoman as Kim Jiyoung — essentially the “Jane Smith” of South Korea. Like many women in Korea, she has delayed her education to support her two younger brother’s goals of graduating from prestigious universities and delayed her marriage in order to build a career. As soon as she marries, the pressure to have a child overwhelms the couple, physically, emotionally, and economically. Kim Jiyoung can’t afford childcare, so she must quit her job—killing her career and limiting her future employment to waitressing or piecework. Though her husband “shares” in the burdens she bears, Kim Jiyoung points out that she carries the bulk of the load and suffers the essential losses. As a family feast day approaches, she begins slipping into the voices and mannerisms of her mother and mother-in-law, as well as a friend with whom she attended college. Her husband is alarmed that she has no recollection of the episodes and fears that she will enter a fugue state and lose herself in one of these characters. Worse, once in these states, she speaks the thoughts these women would otherwise not dare to speak. Cho salts the work with reference to shifts in modern laws regarding marriage, inheritance, and women’s rights while demonstrating that in spite of progress, longstanding patriarchal traditions take a crippling toll on Korean women. The publication of the book inspired feminist groups as well as the Korean #MeToo movement. A movie version was released in 2019, reigniting debate over the novel. When the pop star Irene from the K-Pop group Red Velvet mentioned in a blog post that she was reading Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982, fans flooded her site with photographs and videos of them burning photographs of her.

“It was a given that fresh rice hot out of the cooker was served in the order of father, brother, and grandmother, and that perfect pieces of tofu, dumplings, and patties were the brother’s while the girls ate the ones that fell apart. The brother had chopsticks, socks, long underwear, and school and lunch bags that matched, while the girls made do with whatever was available. If there were two umbrellas, the girls shared. If there were two blankets, the girls shared. If there were two treats, the girls shared. It didn’t occur to the child Jiyoung that her brother was receiving special treatment, and so she wasn’t even jealous. That’s how it had always been.” (15)