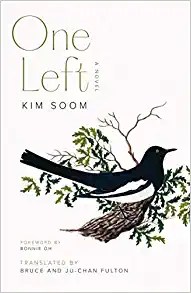

One Left, by Kim Soom

Translated by Bruce and Ju-Chan Fulton

(2016, translated 2020)

(Novel)

Kim Soom’s novel is about a woman who was kidnapped when she was thirteen and taken to Manchuria, where she was forced to become a “comfort woman,” the repulsive euphemism for the two hundred thousand Korean women the Japanese enslaved to provide sex for their soldiers. Though a work of fiction, Kim’s deep research is evident on every page. Footnotes abound, and it is clear that she is creating believable and vivid characters and horrific scenes on the foundation of the testimonies of survivors. The story is set in 1997. The narrator, a ninety-three-year-old survivor, is living alone in a forgotten alley. In 1991 she was shocked to see the momentous television interview of Kim Hak-sun, who broke the silence of her life as a comfort woman. She described her ordeal in detail and called on the Japanese and Korean governments to listen to the voices of survivors, believe their testimony, and seek justice and compensation from the Japanese. The narrator is stunned by Kim Hak-sun’s courage and heartened to know that she is not alone. After her interview, many others came forward. They were interrogated by the Korean government; those who passed through this often humiliating procedure were given the opportunity to live out the remainder of their lives in state-run homes. The narrator, who is experiencing the onset of dementia, cannot envision admitting to anyone what was done to her; instead, he commits to living in silence, following the news about the Comfort Women and the life of the heroic Kim Hak-sun. But in 1997, Kim is dying, and the narrator realizes she will be the “one left.” The author takes us into the mind of the narrator as she recalls the seven years of horrors she suffered at the hands of the Japanese. Calling on testimony from actual survivors, Kim reports on women who were forced to have sex with forty to eighty soldiers a day, whose bodies were ravaged by sexually transmitted diseases, subsisting on weak gruel and insect-infested rice. The Comfort Women owners beat the women, and the soldiers, many of whom were clearly fresh from battle, think nothing of beating, torturing, or murdering them. Should a girl become pregnant, her fetus would be cut from her and her uterus would be removed. Kim’s detached, clinical description of the suffering of the women’s flesh is devastatingly effective. Yet she has a light touch as well, especially when writing of the narrator’s memories of the girls with whom she held captive, many of whom she referred to as “onni,” “older sister.” As harrowing as the tale is, it is a must-read for anyone interested in learning about Comfort Women and sexual violence against women during wartime.

“When five years had passed and her oldest girl hadn’t returned, Mother picked a half a dozen ears of corn from their kitchen garden and went to see the fortune teller who lived out behind the tobacco patch. ‘She crossed the sea and she’s dead and gone.’ Hearing this, Mother adopted a nightly ritual of setting out three bowls of water–one on the soy sauce crock, one on the crock of fermented soybean paste, and one on the crock of hot pepper paste–and bowing to each.” (8)