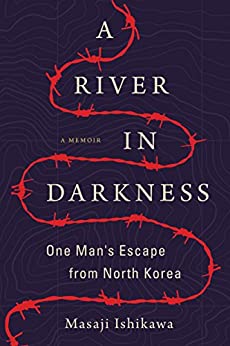

A River in Darkness: One Man’s Escape from North Korea, by Ishikawa Masaji

Translated by Kobayashi Risa and Martin Brown

(2000, translation 2017)

Amazon Crossing

(Memoir)

Ishikawa’s story of escape from North Korea is all the more unique and compelling because he was born in Japan, the son of a Korean father and Japanese mother. His father had been brought to Japan as a young man, dragooned as cheap labor during Japan’s occupation of Korea, from 1910 to 1945. Half-Japanese and half-Korean, Ishikawa belonged to the Zainichi, ethnic Koreans residing in Japan. His family lived with fellow Koreans, which may have given young Ishikawa some sense of belonging, but because of his biracial features, his name, and his fluency in Korean and Japanese, he was bullied in equal measures by Japanese and Koreans. Ishikawa’s father was an angry drunk and a violent gang member who was often jailed or unemployed. As he slips further into despair, his father’s nostalgic memories of North Korea as well as his connection to Korean social service and community groups inspired him to begin to long for home, and soon enough, he begins speaking of his reverence for Kim Il-song. In 1960, North Korea, which was badly in need of laborers, worked with the International Red Cross to negotiate the return of over 90,000 Koreans who had been brought to Japan during the Colonial era. The returnees were promised safe passage and new homes in the Socialist Paradise of North Korea. As Ishikawa observes, North Korea got slaves and the Japanese were able to rid themselves of a population of outsiders who were a painful reminder of their dark past. Despite the wishes of his wife’s family, Ishikawa’s father decided to move the family back “home.” Ishikawa arrived in North Korea when he was thirteen years old, spending the next thirty-six years of his life in a hellish world where he once again found himself at the bottom of a caste system. His voice is direct, sensitive, and yet as hard-edged as a knife as he considers the political forces that caused such needless agony and death for so many powerless and disenfranchised people.

“My grandmother once said to me, ‘Koreans are barbarians.’ I loved her, but I resented her remark. Though I felt Japanese—and felt it with complete conviction—I was half-Korean, as she knew perfectly well. My mother’s elder brothers, Shiro and Tatsukichi, occasionally made similar remarks. They’d been conscripted to serve in the Japanese army in Manchuria and always described Koreans as poor and unkempt, like a bunch of gorillas. They never had the guts to say anything like that in front of my father, of course. But when my father wasn’t around, Shiro would often say, ‘Miyoko had better divorce him as soon as possible. Koreans are just rotten to the core.’”