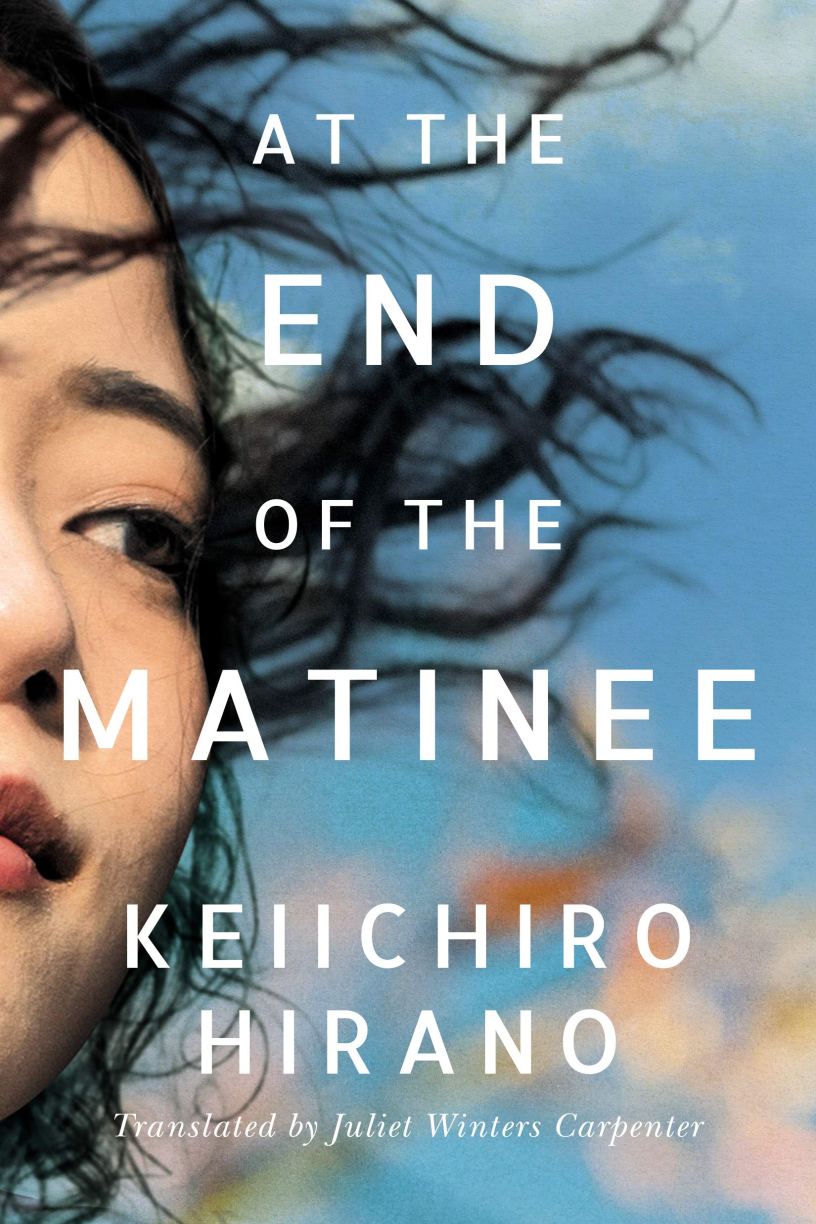

At the End of the Matinee

By Hirano Keiichiro (m.)

Translated by Juliet Winters Carpenter

(2016, translated 2021)

(Novel)

Hirano, also the author of the adventurously plotted A Man— a “who dunnit” that turns out to be a philosophical “who was-it,” presents us with what appears to be a fairly straightforward modern love triangle. The characters are beautiful, their careers are exciting, and the locations are exotic–no wonder that the novel is as popular as it is, and no surprise that it has already been turned into a successful movie. The man, Makino Satoshi, is a successful classical guitarist in his late thirties. He is charming, but he is also in crisis: lately, he has been overcome by devastating bouts of fear during performances. Aso, just as his career is generating enough money for him to live on, the Lehman Brothers collapse set off an international monetary crisis. Then one day he meets Komine Yoko, a Japanese woman who has been working as a journalist covering the humanitarian crisis in Iraq. Few know about her recent experience: after meeting with an Iraqi politician, she passed a man emerging from an elevator. As she entered the empty lift, the man detonated a suicide vest, killing the people with whom she had just been speaking. The two are clearly attracted to each other but can rarely meet. Their best chance seems to come when she is on furlough in Paris and he happens to be on tour. Their story is one of long-simmering passion and unrequited love, but eventually, the “other woman” commits a crime of extraordinary cruelty in order to sabotage the relationship. Here, Hirano focuses on the idea that there are some who seem as if they live their lives as “stars” in their own life story and others who are “supporting actors,” those who accept a position just outside the limelight and devote themselves to the role of handmaiden or water carrier. When Hirano’s “other woman” makes her move from an off-camera voice to a starring role, he and his characters are initially appalled and the chaos she sets in motion causes great pain. The thought-provoking factor that Hirano introduces is time–a topic that the beautiful couple discusses the first time they meet: “‘People think that only the future can be changed, but in fact, the future is continually changing the past. The past can and does change. It’s exquisitely sensitive and delicately balanced.’ Yoko was nodding as she listened, one hand pressing her” (18). The joy in reading the piece is to read it backward and forwards, as the guitarist implies, like a fugue. After the Matinee reads a little like a superficial confection at first, and maybe it is simply an exceedingly well-crafted k-drama. In the end, though, the mood Hirano creates is deeply thought-provoking. His reflection on fate, the role of the past and the future, and his perspective are worthy of attention.

“She was disturbed that the sight of an Arab youth had triggered her panic. In fact, she had just written an article that was critical of the sort of Islamophobia that saw every Arab immigrant as a terrorist. That she had exhibited it herself offended her sense of justice. She had a visceral dislike of such prejudice, partly because of her own background, which was racially and culturally far from ‘pure.’” (132)