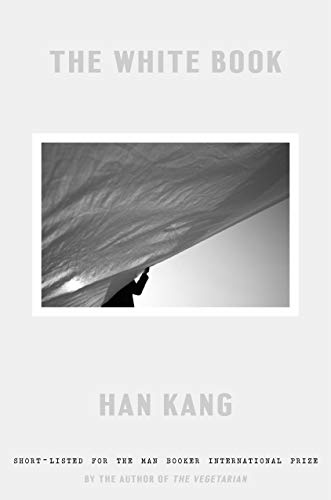

The White Book

By Han Kang

Translated by Deborah Smith

(2016, translated 2019)

Hogarth

(memoir)

The White Book is billed as a memoir, yet Han’s work is primarily a reflection on mourning and death. The inciting incident is a family tragedy. At the age of twenty-two, Han’s mother was pregnant with her first child, a daughter. While her husband was at work, and two months before her due date, her water broke. They lived in the countryside; there was no way to phone her husband or call an ambulance. She delivered the baby on her own. The child, whom she named Seol, “Snow,” only lived a day. Her mother’s second child, a boy, also did not survive. Fortunately, Han herself was born, as was her younger brother. In The White Book, Han takes white, the color of death in Korean culture, as a jumping-off point. She creates a list of indelible instances of profound whiteness and shares the profound sadness experienced by her mother as well as her own despair after her mother’s death. Han also sees the world through the eyes of Seol, first imagining the child’s experiences with her mother during her all too short life and then envisioning Seol’s experience if she had lived. Han is candid about her perceived debt to Seol: from Han’s perspective, she lived because Seol did not. Han’s honesty is not maudlin; at one hundred and forty pages, The White Book is exquisitely concise, efficient, and profoundly moving. And she does not only focus on the personal tragedy her family suffered. Han writes her reflections in Europe, in an unnamed country that was invaded by the Nazis in World War II, a place where citizens were lined up against the walls and shot. She is fascinated by the way the city has rebuilt itself while preserving the memories of the horrors it survived; witnessing the solemn rituals of annual memorials to the dead, she wonders how South Korea somehow has failed to create for its people a way to process the tremendously violent upheavals that it suffered under the Japanese and during the post-war rule by vicious and corrupt dictators.

Sleet

There is none of us whom life regards with any partiality. Sleet falls as she walks these streets, holding this knowledge inside her. Sleet that leaves cheeks and eyebrows heavy with moisture. Everything passes. She bears this remembrance—the knowledge that everything she has clung to will fall away from her and vanish—through the streets where the sleet is falling, that is neither rain nor snow, neither ice nor water, that dampens her eyebrows and streams from her forehead whether she stands still or hurries on, closes her eyes or opens them.