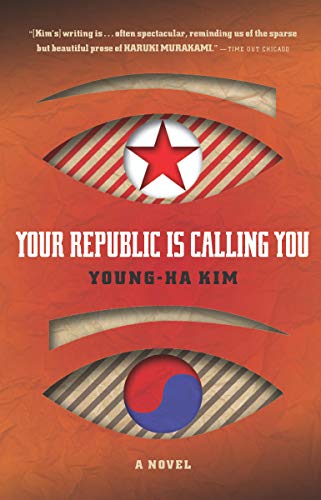

Your Republic is Calling You, by Kim Young-ha

By Kim Young-ha

Translated by Kim Chi-young

(2006, translated 2010)

Mariner Books

(Novel)

Kim’s story is about a North Korean spy embedded in Seoul. Now forty-two years old and a distributor of international art-house films, Kim Ki-yong is married and raising a fourteen-year-old daughter. He hasn’t been contacted by Pyongyang for more than ten years, and so Kim long ago came to the conclusion that the North has forgotten about him and his comrades. Nevertheless, one morning he receives instructions to destroy all evidence of his work and return to Pyongyang by the following day. Kim Young-ha’s novel is a successful espionage thriller, but it is much more than a high-quality page-turner. The work is incredibly ambitious. Kim confines himself structurally to some unique limitations. First, like Joyce’s Ulysses, all the action takes place in a single day. Second, Kim lives for twenty-one years in both the North and the South. Like Odysseus, he is called home and forced to suffer true nostalgia: the pain of the return. As with Joyce, we hear from multiple narrators, among them being Ki-yong, the spy, his wife Ma-ri, and his daughter Hyon-mi. Each of these characters is fully fleshed out and worth learning more about. His South Korean wife was a brilliant student in the 90s, politically active and so swept up in the student movement that she became passionate about Juche philosophy; had she not married, settled down, had a child, and abandoned her radical politics, she would surely have had a dynamic career. As it is, she has fought hard to return to the workforce and maneuver herself into a position where she feels as if she has the chance to make something of herself. She finds her husband to be distant and inscrutable, and she has recently begun a secret life with a twenty-year-old boy. The daughter, Hyon-mi, feels like an orphan in her own home. For example, she tells a friend that her mother is actually her stepmother. She is also trying to negotiate the world of high school, which begins to seem as rife with danger, illusion, performance, and surveillance as the world inhabited by her emotionally distant father. All of the characters are revealed to have built convincing facades that signal to all that everything is just fine, but behind the hard shells,these people are emotionally desperate. Ki-yong is terrified to leave a life he has begun to cherish, his wife is afraid to confront her husband with her wish to end the marriage, and their daughter is testing the dangerous waters of adulthood. Kim is an excellent storyteller, creating characters as vivid as his descriptions of the apartments, bars, underground malls, love hotels, and mass transit of Seoul. Some of his most interesting writing is concerned with free will and fate. One of the most poignant moments in the novel is when Ki-yong visits a fortune teller for advice: the maxim painted on the old man’s tent reads: “Fate is the rock that comes flying at you from the front. If you know it’s coming you can duck, but that knowledge will exhaust your body and soul.”

That haiku, written by Matsuo Basho, is printed on page 67. Ki-yong feels his hands get clammy. He tries to relax by balling his fists and opening them repeatedly. He subtracts 63, the last two digits of his birth year, from 67. Four. The order he has never received. He can’t deny that it has arrived.

This haiku has a prelude, “One Night in Akashi.” Akashi is a Japanese town famous for its octopus. The fishermen, taking advantage of the octopus’s tendency to hide in small places, toss clay jars into the sea at night. In the morning they pull up the jars and capture the octopi. The octopi dream their last dreams in hiding.