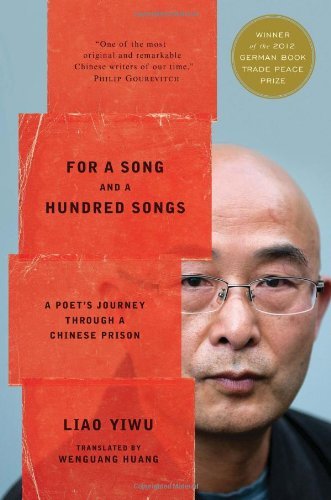

For A Song and a Hundred Songs: A Poet’s Journey Through a Chinese Prison

By Liao Yiwu

Translated by Wenguang Huang

(2013)

New Harvest

(Non-fiction, Memoir)

Mr. Liao, a young, somewhat directionless poet, was in Fuling during the Tiananmen Square protests. On hearing the news over shortwave radio, he immediately composed the poem “Massacre.” In the days following the protests, he performed the piece in clubs, later recording it so that it could be shared with sympathetic audiences. Eventually, he and other artists and technicians shot and edited an abstract film based on Liao’s poems. The Chinese government arrested Liao and sentenced him to four years in prison. Liao openly reveals the arrogance, dissipation, and entitlement of the young artists he associated with before his arrest, and he records his life as a prisoner with equal candor. Beyond starving, electrocuting, and exploiting the prisoners for labor, the guards leave most of the discipline in the zoo-like open-air prison to savage gang leaders who rule over fellow prisoners with violence and psychological cruelty. His status as a political prisoner gives him some protection from the worst crimes, but he suffers unspeakable degradation in the prison system. He writes with humanity about the people he encounters, including guards, thieves, murderers, and fellow revolutionaries. In his final year in prison, he encounters a jailed monk who teaches him to play local folk songs on a traditional bamboo flute. Upon his release from prison, Liao is like a ghost: his wife divorces him, his family is disappointed that he will not try to make his fortune in the go-for-broke embrace of “capitalism with special Chinese characteristics,” and his peers have forgotten him. Liao ends his memoir with his decision to flee China to live in Germany.Liao’s For a Song and a Hundred Songs exposes the extent of the political crackdowns following the Tiananmen Square protests and the lengths to which the Chinese government went to eradicate evidence of the massacre, as well as China’s reliance on surveillance and imprisonment to enforce civil obedience.

“Monk Sima’s past was a mystery to me and to the others, although there was much speculation. One version had the ring of truth: when he was the abbot at a nearby temple, he was accused by the government of belonging to a huidaomen—a superstitious sect. The huidaomen were declared illegal as subversive cults after the Communists took over China in 1949, but many were rumored to be still active in parts of the countryside. When Monk Sima’s case reached police attention in 1982, investigators initially doubted a venerated abbot could be a cultist. But under interrogation Sima refused to speak, so he was deprived of sleep and tortured. After a month, he gave his interrogators just three profound sentences: “I have committed sins. So have you. We are all sinful.” The court sentenced him to life imprisonment.” (370 “The Flute Teacher”)