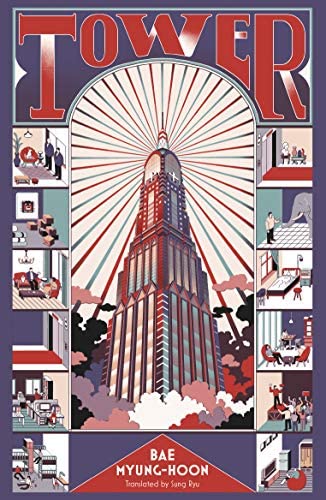

Tower (2009, translated 2020)

By Bae Myung-hoon

Translated by Sung Ryu

(2009, translated 2020)

Honford Star

(Science Fiction)

Bae is a major force in South Korean science fiction. He majored in International Relations and earned his Master’s Degree in the same field; he wrote his thesis on German military strategy in World War I. Bae sets his novel in the near future in a gargantuan building so large and complex that it is its own sovereign nation. Bae admits the nearly seven-hundred-story building, called “The Beanstalk,” is a stand-in for Seoul. For example, just as there is an increasing divide between the ultra-modern capital and the surrounding cities and countryside of South Korea, the Beanstalkians rarely leave their building and a significant number of the citizenry suffer from terraphobia–the fear of being on the ground at street level. There are six interconnected stories in the novel: “Three Wise Recruits,” “In Praise of Nature,” “Taklamakan Misdelivery,” “The Buddha on the Square,” “The Elevator Maneuver Exercise,” and “Fully Compliant.” With “The Three Wise Recruits,” Bae establishes a tone that will predominate the novel: a sense of imminent danger to the building and its occupants, paranoia about Cosmomafia, the geopolitical rival Beanstalkians regard as less culturally and technologically developed, anxiety about unseen forces at work within the Beanstalk, appeals to religion to explain or allay these fears, and a sharp sense of political satire. What is Cosmomafia? Is it North Korea? China? Russia? All of the above? It is important to recall that he wrote the novel in 2008, 2009, a time when he sensed South Korea was ripe for a return to authoritarianism. The democratization movement was in peril. Likewise, he felt that the internet and social media were just beginning to take hold in Korea. It is no surprise then that Bae focuses on low-status academics and researchers who are called upon to study zones of influence and power within Beanstalk by monitoring the exchange of high-value gifts among the nation’s elites. Expanding on Derrida’s assertion that there is no such thing as a free gift, Bae’s mysterious professor assigns a group of interns to monitor the flow of a statistically relevant number of culturally valued, GPS-tagged bottles of alcohol. The team introduces the prized bottles anonymously and then traces their paths as the bottles begin to be regifted. The theory? Whoever receives the largest number of bottles of alcohol will be the most powerful. The only trouble is that the experiment works too perfectly and succeeds in exposing examples of inter-indebtedness that should be best kept hidden. Many of the stories share this idea that numbers of people acting in unison might be more interesting than any individual, as in the story of a fighter pilot who has crashed in the desert. The Beanstalkian hired the pilot as a freelance spy and believes it has no obligation to rescue him, as to rescue him would be evidence that he had value for them. The hero of the story is not the individual pilot nor the one who reveals his plight to the internet: it is the tens of thousands of volunteers who use satellites to search the Balmaklan desert to find the needle in the haystack. Thus, though Bae creates memorable individual characters such as an elephant handler training his charge to perform Hannibalesqe crowd control for the inevitable protests between Verticalists and Horizontalists, his focus is on grand-scale, philosophical issues of humans operating in groups.

“I don’t buy your argument. No matter how you sugarcoat it, what you’re doing seems unethical. How can anyone think of setting an elephant on protestors? It’s incomprehensible to us, as is the fact that you’re proud of your job or that locals marvel at the sight. I resent that the public’s anti-war sentiments are being stamped out like that in the first place. Beanstalk may be swanky on the outside, but it’s downright totalitarian. (“The Buddha of the Square,” 124)