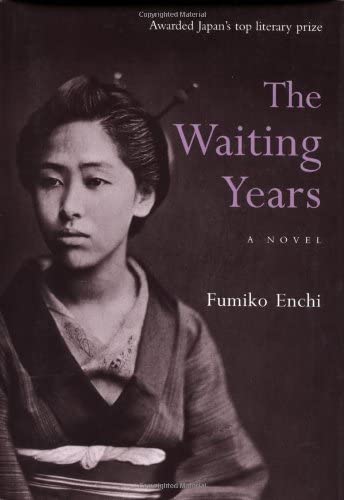

The Waiting Years

By Enchi Fumiko

Translated by John Bester

(1949-1957, translated 1971)

Kodansha USA

(Historical Novel)

Enchi took eight years to write this historical novel set in the waning years of the 19th century. The book is a study of the state of upper-class marriage during the Meiji Period, perhaps as a feminist call to arms or reflection that the empire of the husband had been but little diminished by the War of the Pacific. The opening scene features Shiraka Towa’s visit to Tokyo, ostensibly to visit with former neighbors. We soon realize that she has actually come to the city to observe and interview a young woman prepared to return home with her and live in the family home as her husband’s concubine. Her husband is a shameless philanderer; as his career is flourishing, he will only be under more pressure to visit the city’s entertainment district, spend lavishly, and sample the trade. Unable to modify her husband’s behavior and believing she will be able to maintain some shred of face and agency in the home if she can provide him with a youthful sexual servant, Tomo engages the services of fifteen-year-old Suga, whose middle-class family has fallen into financial straits and is relieved to be able to sell off a daughter. Though her initial experiences with her husband who is twenty-four years her senior are violent and lead to a tragic illness, Suga finds some peace in the household and even becomes a friend and confidant of her lover’s wife. Unfortunately, over the years, Toma’s humiliating maneuver merely feeds the husband’s narcissism, lust, and cruelty. Even as he ages, he demands a second concubine and when it comes time to renovate their family estate, he arranges for the architect to move his wife to a distant corner and establishes his favorite in the room adjoining his own. Tomo is forever suppressing her own feelings and surprisingly, she becomes one among equals of the various women who scurry behind the scenes to sate the master’s whims and to keep the household running. There are happy moments: when Yuri becomes the second concubine, Suga takes on the role of her elder sister and they become great friends. However, when Yuri chooses to marry in her late twenties and leaves the house, Suga is almost broken; she never makes a connection with the final concubine, Miya. Comparing the adolescent body of Miya with Suga, who is now in her thirties, the husband declares the obvious in the cruelest way possible: since Suga’s body no longer pleases, and no man will have her because she is barren (a physician explains that her deflowering caused the condition), it is best that she serves as a nanny to his children. And although Tomo hopes that her self-sacrifice will be rewarded at her husband’s death, his flamboyant lifestyle and poor management of his fortune suggest she will be unsupported in her old age. Tomo lives long enough to see her own children mature. Her daughters and her friend’s daughters seem to enjoy a degree more freedom in their marriages–perhaps that is the final hopeful note in this novel where masculine authority is unchecked and women must simply endure its petulant blasts.

“Such a husband was no object for her love, such a life no more than ugly mockery. She stood in desperation in this sterile wasteland, firmly clutching Etsuko’s tiny body to her, while she was mercilessly robbed of the husband she was to have served and the household whose mainstay she was to have been. She knew that to fall would mean to never rise again.” (52)