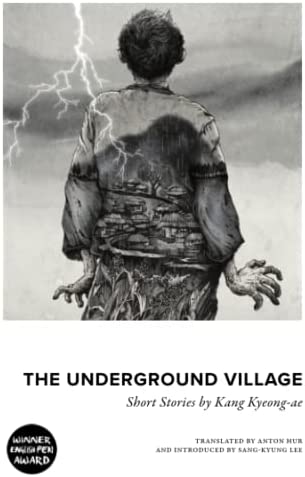

The Underground Village

By Kang Kyeong-ae

Translated by Anton Hur

(2018)

Honford Star

(Short Story Collection)

The work of Kang Kyeong-ae is essential reading for anyone interested in the complex history of Manchukuo, the puppet state established by the Japanese in 1931. Located in China’s Northeast, the land was formerly known as Manchuria. This was previously a semi-independent province under the governorship of Zhang Xueliang. During the Japanese Annexation of Korea in 1910, many Koreans fled to Manchuria. By 1930, there were 2 million Korean migrants in this region who operated under a pact of mutual protection and stateless communism. Koreans were technically under Japanese rule, but they also faced threats from exploitative Chinese landlords, warlords, and bandits. The lives of all the characters in Kang’s stories are brutal. Everyone appears to be impoverished, desperate to survive and bitter to have fled their homeland to a land with poor soil and limited resources, while also under the constant threat of robbery or violence. Kang’s protagonists and narrators are predominantly women. One’s husband dies of disease and communists execute her teenage son; without protection, she is exploited first by one family and then another. An educated Christian missionary, pale beneath her make-up, chastizes a flock of threadbare peasants for their failings. A young nurse in a small clinic suffers heartbreak when a dishonest doctor throws her over to marry another. In another story, a woman makes a dramatic and perilous journey across the country in order to visit her dying mother, a woman she has not seen in five years because she has not been able to afford the fare. Written between 1931 and 1935, the stories speak of the heart-stopping consequences of poverty and political chaos. The title story, “The Underground Village,” embodies the worst of human suffering. Here the consequences of a complete breakdown of civilization are nothing less than unspeakable, as the people in this village are those whom society has absolutely failed. Unable to even afford the means of basic hygiene or modern medicine, parents pin their hopes on healing eye infections with urine or attempting to heal the festering sores on a toddler’s scalp by binding it with the skin of a rat. One child’s body is twisted, his hands useless after he contracted a virus as an infant, a local woman gives birth to blind daughters, and a furiously hopeful matriarch is finally broken when she finds that she can no longer produce milk for her child. In the midst of the high-stakes power struggles between ethnic groups, nations, Hans and Manchus, Korean Anarchists and Chinese Communists, the Japanese army, and the colonizing Japanese, Kang documents the cost to the most vulnerable.

“The beach at Gumipo is one of the most beautiful in the East, with five to six hundred American missionaries visiting it every summer. Hyoungchul’s family had built a house a little further up the mountain, in a town called Bongnae which had about two hundred new residences. They had a view of the endless Yellow Sea to the front and of the twisting Bultasan Mountain behind. Hyoungchul and Hyegyoung got on a boat and left the ship behind.

An American flag flew high above the town of Bongnae as they made their way across the rough waters.

I am a pitiful son of Korea, you a pitiful daughter of Korea … Filled with such thoughts, Hyoungchul gazed surreptitiously at Hyegyoung. His eyes welled up, blurring his sight.”

–“Break the Strings”