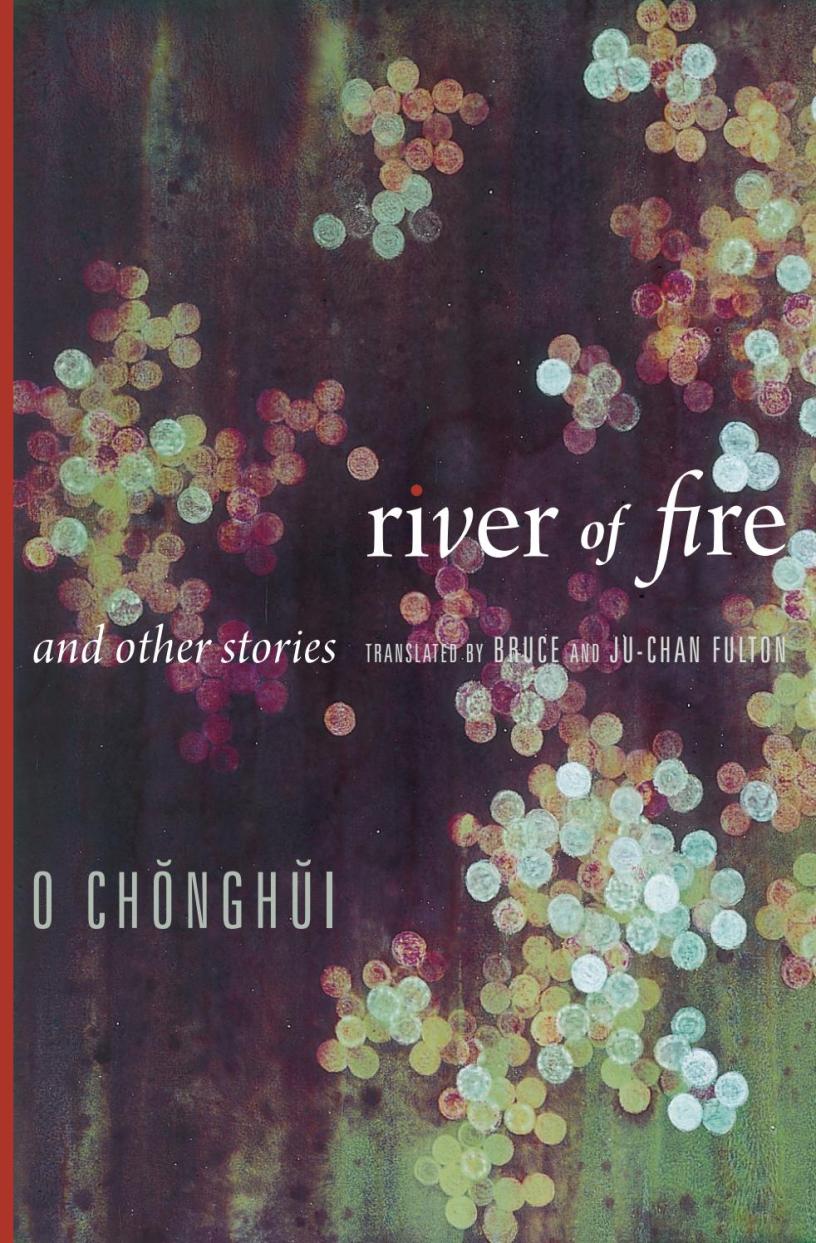

River of Fire, by O Chong-hui (also Oh Jung-hee)

Translated by Bruce and Ju-Chan Fulton

2016

Columbia University Press, Weatherhead Books on Asia

(Short Story Collection)

O Chong Hui was born in 1947, a significant time. During the Japanese colonial period, all Koreans were required to speak Japanese. O was therefore among the first Korean students to be educated in their native tongue and trained in using the hangul writing system. She is also part of the Liberation Generation, experiencing the First Republic 1948-1960 through the 5th Republic 1979-1987, a time of political unrest, stagnant economic growth, strong-man rule, military coups, and assassinations. O witnessed “The Miracle of the Han,” which took hold in the 1970s through the 1990s; despite the remarkable economic recovery of her country, O’s work focuses mainly on the political struggles within the traditional Korean family and the dilemmas faced by Korean women.

O is considered a master of the short story, a form that is highly regarded in Korea. The collection, which includes nine stories, begins with a piece O wrote while still in high school, “The Toy Shop Woman.” The protagonist is an obsessive, mentally ill young girl. When her parent’s relationship comes undone, she tries to hold the fragments together by caring for a wheelchair-using brother and stealing whatever she can find from the desks of her classmates. She also burrows her way into the arms of a middle-aged toy shop owner, a woman older than the hero’s mother, a double amputee, who also suffers deep emotional trauma. In “One Spring Day” a long-married couple share an addiction to Coca-Cola and little else. Though now middle-aged, the wife is still haunted by her efforts to abort her pregnancy at six months or end her life. Today, to fight off the sense that her body is once again filling up with another being, a spirit no doubt intent on drowning her, she attempts to distract herself by seducing one of her husband’s card-playing buddies. In the title piece, “River of Fire,” a listless, loveless couple exhausted from work in a garment factory and piecework, watch from their tiny apartment as military work units use dynamite to level a nearby island in preparation for building a strategic airport, while a massive power plant that somehow survived the bombing of Seoul, looms like a stubborn relic. The young husband recalls being a child refugee and living on a spit of land on the Han River, idle days spent in the shadow of the plant. How long will it last before the nation decides to erase this empty landmark, too?

Not all of O’s tales tread the razor’s edge of madness. “Morning Star,” for example, chronicles the emotions of a married woman out for tenth-year reunion drinks with her friends from their college newspaper. Once all writers, most have settled into different careers. There are exceptions; a particularly beautiful woman works for a travel magazine, and the class poet continues to write, though he is still unpublished and only just making a living. The main character, Chonghae, is the mother of two and the primary caregiver of her husband’s mother, who is deaf and may be suffering from dementia. Chonghae can’t remember the last time she left the house, and an overheard whisper suggests she has aged dramatically and looks haggard. Though we have every reason to believe she will go home come morning, it may be that she will not see a night as “free” as this in her lifetime.

(O’s works, the short stories “Wayfarer” and “Words of Farewell” appear elsewhere in this project.)

“None of them tried to hide the facts—that Mother had developed childbed fever after giving birth to me, that the toxin had settled in her legs and made her virtually lame, that finally she’d been possessed. Whenever a shaman ritual took place, you could see Mother in her sky blue jacket, crimson skirt, long indigo vest, and black shaman’s hat, her fan and bells in hand.

She was a tall, raw-boned woman, which paradoxically made her look all the more nimble as she balanced herself and performed her jumps on the blue steel of the two straw-cutter blades, with nary a nick on her feet to show for it. But by the time she finished the ceremony she could barely stand, and she had to squat like a crab as she took leave of the gathering.”

– “A Portrait of Magnolias”