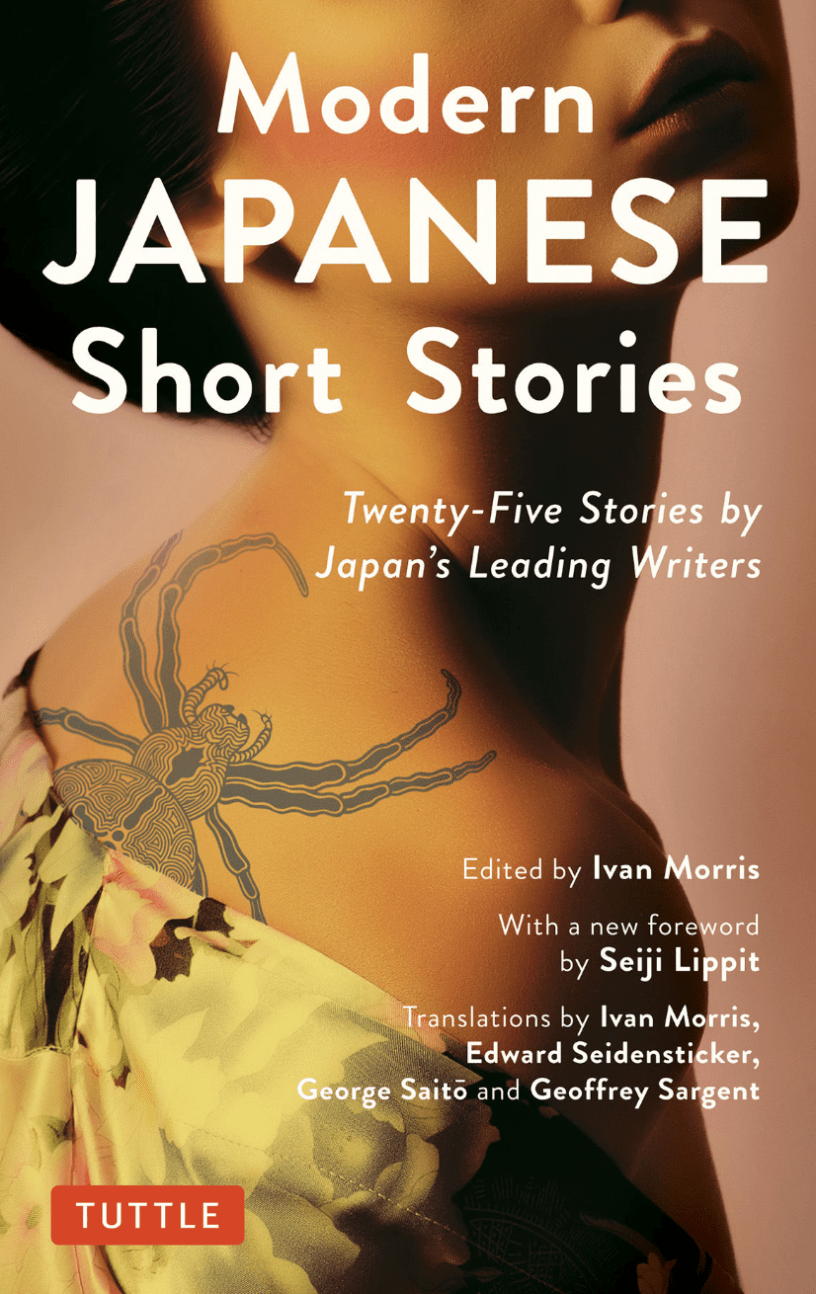

Modern Japanese Short Stories

Edited by Ivan Morris

(1962, 2019)

Tuttle Publishing

(Short Story Anthology)

The Morris or Tuttle Modern Japanese Short Stories is a historic production: it is the first publication of Japanese short stories in English, and thus, the first introduction to Japanese literature for a generation of English-speaking readers, writers, and historians. Ivan Morris was part of a four-man team of famed translators including George Saito, Geoffrey Sargent, and Edward Seidensticker. Morris selected roughly half of the twenty-five short stories. Remarkably, the remaining stories were chosen by Kawabata Yusanari, the first Japanese to be awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, as well as representatives from the Japanese National Commission for UNESCO.

“Under Reconstruction” (1910)

By Mori Ogai (m.)

Translated by Ivan Morris

Mr. Mori sets this piece in the Ueno district during reconstruction after Japan’s victory over Russia in the Russo-Japanese War. Mori was a proponent of the “I novel” or “confessional novel.” He casts himself in the role of the narrator in many of his stories. In one of his most memorable works, he describes his youthful pursuit of a European ballerina he met while studying medicine in Germany. In that story, young Mori is enchanted by all things Western and regards his country as a cultural and educational backwater. “Under Reconstruction” presents us with a mature Mori, someone who has rediscovered pride in his nation and who has seen more than enough of the consequences of Japan’s reckless pursuit of modernization and Westernization. The narrator is a middle-aged Japanese man who has come to a Western-style restaurant to meet with a female singer/entertainer he met long ago while studying medicine in Germany. The restaurant itself is under construction. It is loud and cluttered with building materials. The staff is poorly trained and done up as European waiters and the décor is a displeasing mashup of European and Japanese artwork. This proxy for Mori is no longer the smitten college boy. He regards his former lover cooly. She informs him that for professional purposes she has taken the name of her Polish accompanist but suggests that she would like to rekindle the relationship she and the narrator enjoyed once before in a different time and place.

“Watanabé sat down on the sofa and examined the room. The walls were decorated with an ill-assorted collection of nightingales on a plum tree, an illustration from a fairy tale, a hawk. The scrolls were small and narrow, and on the high walls they looked strangely short as if the bottom portions had been tucked under and concealed. Over the door was a large framed Buddhist text. And this is meant to be the land of art, thought Watanabé. (41)

“The Order of the White Paulownia” (1935)

By Tokuda Shusei (m.)

Translated by Ivan Morris

Tokuda wrote many of his stories about the lives of average people in Japan and he often focused on the plight of married and unmarried women. In this example, we meet Kanako. After coming of age, steps were taken to arrange a marriage with the son of a well-to-do and influential townsman. The relationship was progressing nicely and Kanako appeared delighted with the match until suddenly, her future-father-in-law renegotiated the arrangement. Instead of marrying his eldest to Kanako, he arranged for Kanako to marry his beloved second son who had just returned from the war. Surely Kanako was disappointed, but her family made no objections. What Kanako did not know is that her father-in-law had discovered that army service had introduced his son to the excesses of drinking, gambling, and whoring, and he was arranging the marriage as a way to temper the son’s dissipation. The title refers to a military honor awarded to the profligate veteran for his military service..

“Kanako noticed that the Korean scrap pedlar used to change into a neat cotton kimono every evening as soon as he came home from work and that e would then take his children out to the public bath. People say a lot of unflattering things about Koreans, thought Kanako, but Koreans can be a lot kinder than Japanese men. The scrap pedlar’s wife used to speak to Kanako at the back door, and Kanako began to wonder whether this woman’s marriage to a foreigner might be happier than her own.” (60)

“Hydrangea”

By Nagai Kafu (1931) (m.)

Translated by Edward Seidensticker

Mr. Nagai wrote was a proponent of French-influenced Romanticism. He spent several years living in France and was greatly inspired by Maupassant. Not surprisingly, on his return to Japan, he often wrote about characters from the demimonde. In this story, the main character is a male samisen player. He frequents the pleasure districts of Edo making just enough money to keep an older geisha who still has some social cachet but who torments him with her condescending attitude. A sensualist, the musician cheats on his lover, involving himself in a relationship with a young geisha of the lowest class. Overcome by desire, he uses all his money to buy the girl’s freedom. His actions violate the strict codes regarding geishas and their houses and cost him his status as an entertainer. His master and teacher have no choice but to cast him off and he becomes both unemployed and unemployable in the pleasure districts. The narrator is on the horns of a dilemma as he is obsessed with his relationship with the child while completely aware that he is in her thrall and that he cannot trust her. He calls her “Hydrangea” because she “will change colors half a dozen times a day.” As the months ear on and they resort to selling off their clothes, he becomes convinced he has a rival. As his jealousy rises he descends deeper into monomania.

“She was just nineteen. She had begun seeing men when she was no more than thirteen or fourteen, and after leaving home and making the rounds of the provincial teahouses, she had emerged at Shitaya at the end of her seventeenth year. Suited by nature for the trade she had chosen, she was fairly much in demand and had decent enough customers; but she was not one to worry about her future.”

“Seibei’s Gourds”

By Naoya Shiga (1913) (m.)

Translated by Ivan Morris

At a time when writers were pursuing a dark and cold naturalism, Mr. Shiga joined the White Birch Movement and embraced an idealistic vision of humanity that was strongly influenced by Tolstoy. He is famous for his exquisitely terse style; he pares down his work with a very sharp knife. The hero of this story is a young boy, Seibei, he becomes enamored by the craft of hollowing out and preserving gourds. A different sort of boy, he spends his free time looking for the vegetable that speaks to him. Then he begins the painstaking process of removing the seeds, drying, and polishing each one until it shines. Adults point out to him that although his work is good, he is wasting his time preserving such ordinary, plain specimens. According to them, the real money is in preserving the most curious looking of gourds. Trouble begins when a Nationalist, macho teacher catches the young artist working on his craft at school and visits the boy’s home in order to humiliate him before his parents.

“Seibei’s mother was sobbing softly. In a querulous whine she began to scold him, and in the midst of this, Seibei’s father returned from his shop. As soon as he heard what happened, he grabbed his son by the collar and gave him a sound beating. ‘You’re no good!’ he bawled at him. ’You’ll never get anywhere in the world the way you’re carrying on. I’ve got a good mind to throw you out into the street where you belong.’” (90)

“Tattoo”

By Tanizaki Junichiro (1910)

Translated by Ivan Morris (m.)

Tanizaki and Nagai became proponents of Neo-Romanticism, though Tanizaki embraced even darker, more sensual and hallucinogenic writers like Poe and Baudelaire. As in “Hydrangea,” the tone is nostalgic, serving as a remembrance of a time when men and women valued beauty and desire above all. As the narrator explains, it was a time when powerful young men subjected themselves to the needle of the tattooist to accentuate the innate splendor of their bodies. The most beautiful and accomplished of courtesans would seek out these men, competing furiously for the pleasure of being possessed by them. One of the tattooists is Seikichi, a painter of some fame who lowered himself to work directly on the body. Known for his “voluptuous” work, he just barely conceals the exquisite sexual desire he experiences as he produces his line drawings on male bodies. His greatest fantasy is to someday find an ideal woman, perfect in beauty and character, on whom he can draw his masterpiece: a representation, as it were, of his very soul.

“When he had to deal with a faint-hearted customer whose teeth would grind or who gave out shrieks of pain, Seikichi would say” ‘Really, I thought you were a native of Kyoto where people are supposed to be courageous. Please try to be patient. My needles are unusually painful.’” (95)

“On the Conduct of Lord Tadanao”

By Kikuchi Kan (1918) (m.)

Translated by Geoffrey Sargent

Mr. Kikuchi’s “On the Conduct of Lord Tadanao” was so popular that it inspired other writers to mine Japan’s medieval history and reimagine episodes in the lives of these legendary heroes. In this story, Kikuchi addresses a puzzle: why did the powerful Daimyo of Echizen, Lord Tadanao, abandon his title at the age of thirty and take vows at a Buddhist temple? Kikuchi’s tale is provocative, full of combat, sexually titillating, and philosophical. The story has a heavy-handed and surprising theme: when we consider the warlords and nobles of the past, we must pity them, for they too were bound by cruel laws and conventions of the shogunate. This, though they may appear to live like gods on earth, their societal role causes them immeasurable suffering. Lord Tadanao inherited his landholding of 3,350,000 bushels at the age of thirteen. At twenty, he is entitled, arrogant, petulant, and quick to fly into a rage. He was also superior to all in martial arts, game-play, and sports. It is his willfulness that causes him to ignore a call to arms from His Excellency Ieyaso to join the attack on Osaka Castle, and his inability to take criticism that incites him to honorable conduct the next day that raises him to new heights of glory. He strides with exaggerated confidence knowing that he is superior to any man in the kingdom. Everything changes, however, when he overhears two of his retainers talking about his performance in a competition against three men in which he brandished a three-yard spear blunted with leather.

“Ukon’s words were with him still, echoing loudly in his mind. Lord Tadanao tried to calculate just how much of each splendid feat today had been due to himself, and how much to deceit. But it was no use. And it was not only about today that he would never know. Among all the countless victories and distinctions he had gained through childhood, in every variety of contest or skill, he would never the what had been the proportion of reality and pretense.” (120)

“The Camellia”

By Satomi Ton (1923)

Translated by Edward Seidensticker

A crucial detail of this brief story is that it was written and published shortly after the Tokyo-Yokohama earthquake of 1923 which killed over 140,000 people. There are just two characters, a young maiden and her aunt. They are sharing a futon on their first night in their new home when they are startled by the sound of a camellia that has fallen from a vase—blood-red or white, a fallen camellia is a harbinger of death in Japanese folklore. The story’s tone is reminiscent of those silent days immediately after the 9/11 attacks on the United States.

“In the alcove, several feet farther away than she would have guessed, a large crimson camellia had fallen. It lay on the matting like a turned-down bowl. They had hated to leave their camellias in their old garden and had had their agent break off an armful, which they had brought with them. The celadon vase in the alcove was full of week-old camellias.” (143)

“Brother and Sister”

By Muro Saisei (1934) (m.)

Translated by Edward Seidensticker

But for the coarse language, Mr. Muro’s “Brother and Sister” may be the perfect introduction to the ways many societies view the sexuality of young men and women with remarkably biased eyes. We are in the realm of Akaza, a natural leader of men, unafraid of using his voice or his fists against workers or his family. He runs a squad of men who hire themselves out to repair dykes along the river and at the mouth of the sea. They build bamboo baskets, fill them carefully with just the right combination of large, medium and small stones, and then dive beneath the water to position them on the river floor, pinning them in place with bamboo spears. Akaza and his wife, Riki, work as a team. She manages the books and pays the men, and she also provides food and drink when their spirits need buoying. They have a son, Inosuke, who is educated but irresponsible and a womanizer. They also have two daughters. Both were sent off to work as maids in Tokyo. One is a model child. The other is Mon, a girl who fled the family in shame after she was seduced by a country boy and left pregnant. The family clearly misses her but they are intolerant of her new lifestyle. Her illegitimate child was stillborn. Without emotional or monetary support from her family, she works in bars and finds shelter with lovers in whom she has no lasting interest. After a long absence, Mon returns to shelter at her family home, idling the day away and sleeping past noon, behavior that causes her mother to suspect that her wayward daughter may be pregnant again. Shortly after her arrival, Kobata, the young man who first seduced Mon, returns, begging for forgiveness and offering to take responsibility for providing for the child. His appearance on the scene triggers a number of interpersonal conflicts which threaten to break out into violence.

“As is the way with men who work in the sun, he was sunburned even to his eyes—eyes that seemed to have been made for the river…He had lived with the river since he was six, he was a full-fledged stoneman at fourteen, he came to manhood with his feet lacerated by bamboo splints. Even so, the terror of the flood was new each year. How did it manage to take away one hundred massive rock baskets?

“The House of a Spanish Dog: A Story for those Fond of Dreaming” (1916)

By Sato Haruo (f.)

Translated by George Saito

Mr. Sato, a fantasist, was strongly influenced by writers like Edgar Allen Poe and Oscar Wilde. In this story, he also seems to have been influenced by European folktales and perhaps by stories of the Christian saints. The idle narrator is out walking in the village with his faithful dog Fraté when he decides to let the animal follow its fancy. They exit the hamlet along a route never before tried, and some two hours later they have gained both distance and elevation. The dog has taken his master to a small abandoned cottage. Peeking in through the window, the narrator discovers that the house contains a bubbling fountain. After calling out, master and hound enter the cottage where they find a library, a still-burning cigarette, and a welcoming Spanish dog.

“After another half hour or so of walking, Fraté stops once again. He gives out a couple of staccato barks. Until this moment I had not noticed it, but now I see that a house is standing directly in front of me. There is something very strange about it. Why would anyone have a house in a place like this?” (168)

“Autumn Mountain” (1921)

By Akutagawa Ryunosuke (m.)

Translated by Ivan Morris

Mr. Akutagawa probes the traps inherent in criticism, interpretation, communication, memory, and the appreciation of fine art. After a pleasant dinner, Wang asks his host Yun if he has ever seen the painting “Autumn Mountain” by the famed artist Ta-Ch’ih. Immediately, Yun conjures in his mind the artist’s legendary scrolls “Sandy Shore” and “Joyful Spring.” But “Autumn Mountain”? Surely he had never heard of it. Yet if Ta-Ch’ih did paint such a scroll, by all means, Yun must see it. And according to Wang, the beauty of “Autumn Mountain” outstrips even Ta-Ch’ih’s “Summer Mountain” and “Wandering Storm.” Wang claims he saw this exceptional work at the home of Chang in the County of Jun. But although Wang can reconstruct the picture from memory, he must also confess to that he may have never seen “Autumn Mountain” at all.

“At the first glance, Yen-k’o let out a gasp of admiration. The dominant color was dark green. From one end to the other a river ran its twisting course; bridges crossed the river at various places and along its banks were little hamlets. Dominating it all rose the main peak of the mountain range, before which floated peaceful wisps of autumn cloud…This was no ordinary painting, but one in which both design and color had reached an apex of perfection.” (179)

“The Handstand” (1920)

By Ogawa Mimei (m.)

Translated by Ivan Morris

Mr. Ogawa focuses on overqualified, underemployed workers. His narrator is a man trained in the fine arts but who can only find work painting on tin billboards. As he turns his eye toward the pedestrian examples of advertising, he recognizes that he is not alone: here and there he recognizes that the creators of some ads have invested in their work not only great thought but also inspiration. Between jobs, he hangs out with other regularly unemployed men and gets to know their stories. Kikichi was an engineer’s mate and Cho a tinsmith. They talk about girls, the slow economy, gambling, and dreams. Kikichi says that he might take up the flute. His peers rib him, but Cho says that any man can succeed if he only practices. To prove his point, he tells how he once saw the most beautiful girl in a circus. She cast a spell over him and he determined that he could become as strong and as graceful as her. She climbed twenty feet in the air and then stood on her hands and crossed a narrow beam high above the crowd. From that day, he practiced her moves on the ground until he felt that he was as skilled as the gymnast. Days pass. A miner joins the group. He says he’s been working at the Aso mines and tells horrifying tales of the dangers he has faced. His plan is to look for a position as a lathe worker; if that doesn’t work out, he plans to travel to Nikolaevsk. Men in suits appear and try to inspire them to join a labor union. As the hours of idleness take a toll on their spirit, the three friends decide to hike across town to climb the scaffolding surrounding a new chimney that dominates the skyline.

“While you’re down there in the mine, you’re so busy with your work, you’re so damned glad you haven’t had an accident yourself and trying so hard to watch out in the future, that you don’t have time to worry about anything else. It’s when you come out on the surface after a day’s work that you start thinking. You see other people walking about up there who’ve never been down in a mine in all their lives. And you get to asking yourself: “What the hell! I’m no different from them. What do I spend all day down in that damned hole for?” (193)

“Letter Found in a Cement Barrel” (1926)

By Hayama Yoshiki (m.)

Translated by Ivan Morris

Mr. Hayama was an adherent of the proletarian school. His writing is blunt, journalistic, and it drives hard at predictable themes. The main character is Yoshizo Matsudo, whose task is to open barrels of cement and feed it into the mixer over an eleven-hour-long shift. Just before he knocks off for the day he opens a barrel and discovers a small sealed wooden box. He puts it inside his shirt and then struggles to wash the cement dust from his caked body. Before going home to his pregnant wife and their six children, he smashes open the box and reads a curious letter written by a young woman who fell in love with a co-worker at a cement factory.

“Matzudo Yoshizo was emptying concrete barrels. He managed to keep the cement off most of his body, but his hair and upper lip were covered by a thick gray coating. He desperately wanted to pick his nose and remove the hardened cement which was making the hairs in his nostrils stand stiff like reinforced concrete; but the cement mixer was spewing forth ten loads every minute and he could not afford to fall behind in its feeding.” (205)

“The Charcoal Bus” (1952)

By Ibusé Masuji (m.)

Translated by Ivan Morris

Mr. Ibusé tells a story of a clap-trap bus that was converted to run on coal during World War II and continues to serve a remote countryside route. The bus is notorious for breaking down, but the citizens are dependent on it for its service. The bus driver is a martinet, the conductor, who was demoted from his position as driver, is bitter, and the regular customers are resigned to the reality that they will have to push the bus a significant portion of the route each day in order to make a connection to one of the more reliable routes. There is also a young newlywed couple aboard. First-time customers, they do not understand that they need to get out and push the vehicle. Mr. Ibusé’s portrayal of the bus, its driver, and its passengers is a thinly disguised critique of Japan’s post-war struggles.

“Not only did I and the regular passengers regard the driver as a disagreeable bully, but we also despised him for his inefficiency in handling the bus. The constant delays and breakdowns used to leave him quite unperturbed. As soon as the engine failed, he would announce in a stentorian tone: ‘All passengers out! Start pushing!’” (214)

“Machine” (1930)

By Yokomitsu Riichi (m.)

Translated by Edward Seidensticker

Describing Yokomitsu’s Neo-Sensualist style, editor Ivan Morris helpfully reports that the reader can expect “startling images, mingled sense perceptions and an abruptness of transitions” (222). Yokimitsu counts odd bedfellows as his influences, such as the Dadaists who practiced automatic writing, as well as Joyce and Proust. “Machine” is a challenging read. The narrator is a low-ranking worker in a metal etching plant. The plant manager is a man in his forties who has a mind well suited to metallurgical invention but who can’t be trusted not to misplace a penny or the entire payroll and has the maturity of a five-year-old. The narrator’s task is to mix and apply the toxic chemicals and compounds to treat the metals. Although he learns quickly that exposure to these chemicals adversely affects his mind and nervous system, he decides that he will continue in this position until he at least learns the trade and some of the proprietary secrets. Soon a rival worker appears, Karubé, who correctly assumes the narrator’s motives. Unsurprisingly, the narrator becomes paranoid, convinced that his observer is behind falling hammers and disappearing metal punches. He even suspects that the man might poison his coffee. Then the plant receives an order to produce 150,000 name plates and the owner hires another worker, causing the narrator and his rival to form an uneasy alliance and unleash their chemical-fueled paranoia on the new man. A death ensues, but whether it was intentional or an accident remains a mystery. From the narrator’s perspective, it may have been the cause behind all events: “the machine.”

“Shoving my head deep into the cuttings, he rubbed it back and forth as if the metal were a washcloth. I visualized my face being polished by a mountain of little plates from house doors and thought how disturbing violence could be. The corners of the aluminum stabbed at the lines and hollows of my face. Worse, the half-dried lacquer stuck to my skin. Soon my face would start swelling.” (230)

“The Moon on the Water” (1953)

By Kawabata Yasunari (m.)

Translated by George Saito

Like Edogawa Rampo, Kawabata explores the mechanical and spiritual properties of mirrors. The central figure is a young woman who marries at the start of the Greater East Asia War (World War II). Because of the conflict, the couple did not enjoy a honeymoon and within three months, tuberculosis had invalided her husband. Well into her husband’s illness, she ponders her beauty in the reflection of a table mirror. Toying with a hand mirror, she is able to see the back of her neck and shoulder. The experience immediately makes her as self-conscious as the first time she was alone with her husband. Experimenting further, she discovers ways that her bedridden husband can see her as she moves about the room. Thunderstruck, she realizes that she can place mirrors in such a way that her husband can see her even when she is out in the garden, a discovery that brings them both great satisfaction. She uses the mirrors to help him see the moon and the blue skies, and he finds a way to use the mirror to signal her when she is outside. Throughout, the woman wonders about the degree to which the mirrors alter reality, intensifying some colors and diminishing the powers of others. And she wonders about the woman her husband sees in the mirror. Is that her or some figure that has its own existence apart from her? Eventually, when her husband succumbs to his illness, the widow remarries. Her treatment of the mirrors used by her first husband is a beautiful ritual, while her use of a new mirror–a wedding gift—introduces the woman for the first time to a self she can recognize.

“Kyoko was amazed at the richness of the world in the mirror. A mirror which had until then been regarded as only a toilet article, a hand mirror which had served only to show the back of one’s neck, had created for the invalid a new life. Kyoko used to sit beside his bed and talk about the world in the mirror. They looked into it together. In the course of time it became impossible for Kyoko to distinguish between the world that she saw directly and the world in the mirror. Two separate worlds came to exist.” (250)

“Nightingale” (1938)

By Ito Einosuké (m.)

Translated by Geoffrey Sargent

Mr. Ito’s “Nightingale” is a fast-paced, delightful drama set almost entirely in an extraordinarily-busy police station in a rural community. Written in 1938, it seems to have anticipated the form of a situation comedy—something like a Japanese Barney Miller. Ito clearly loves each of his characters and presents us with a police force that might be impatient at times but is overwhelming just and beneficent. The captain and his staff make it their business to listen carefully both to the villagers’ complaints and the responses of the accused. I’m not sure any police force has ever acted in this way—apart from Mayberry RFD—but the manner in which they tame the chaos and bring satisfaction to all parties is wonderful to witness. Some of their challenges involve a missing person’s report of a child who disappeared twenty years ago, a phony shaman who is bilking old ladies out of their savings, and a Party-Trained OB-GYN who can’t get women to visit her clinic because a local widow is passing herself off as a doctor and midwife.

“Just lately a qualified midwife had come to work in the district, sponsored by the Prefectural Health Authority, but until her arrival it had been the universal custom at the time of birth—unless a midwife was called in from a neighboring district, or the patient brought about her delivery unaided, heaving on a rope suspended from the ceiling—to go running off to Yaé’s place. After the death of her husband, Yaé had come to rely for her subsistence almost entirely on the rice or bean curd given to her in appreciation of those services, and gradually came to feel that this was her profession.” (282)

“Morning Mist” (1950)

By Nagai Tetsuo (m.)

Translated by Edward Seidensticker

“Morning Mist” features a style that was common in Japanese magazines, a sort of mash-up of a themed essay and an illustrative narrative, though in this example Mr. Nagai transcends this form in the last pages of his story, launching off into a lyrical flight from the material conundrum he has been wrestling with, perhaps having been transformed by the experience of relating his story. The inciting incident involves a thwarted attempt at marriage. Yoshihidé, a college friend, contacts the narrator, seeking his advice on this question: is the woman I have chosen to be my wife worthy of me. When the narrator assures Yoshihidé that the woman is, in fact, a prize, he asks the narrator if he can persuade his father, “X,” to give his blessing to the union, as “X” is not quite prepared to part with his twenty-five-year-old son who still lives at home—an instance of parental jealousy of a child’s love that not infrequently appears in Japanese fiction and film. As it happens, “X” is wed to routine and cannot tolerate change. This has served him well in his role as a teacher, but his rigidity has grown into something of a mania. Worse, X is suffering from dementia. The more he loses his memory, the more intensely he adheres to routine. The narrator is intrigued by the lengths to which X’s wife and son go to routinize their own interactions with him and takes joy in also adapting himself and inserting himself into X’s shrinking world. But can he convince X to sanction his son’s marriage?

“I myself have been working for nearly ten years now: and it rather amused me once to learn that carp in a fishing pond follow fixed and invariable paths. The working man is very much like the carp. He is most reluctant to move from the familiar rut. Except for pressing business or an emergency, he has no wish to change his route to work, even though he ought to be thoroughly sick of it.” (304)

“The Hateful Age” (1947)

By Niwa Fumio (m.)

Translated by Ivan Morris

Mr. Niwa was raised in a Buddhist monastery and after graduating from college and struggling to find work, he decided to become a monk instead. In “The Hateful Age,” Niwa throws a crate of TNT into the cultural crisis brewing between Confucianism and modernity, shining a light on filial piety and the aging post-war population. The central character is old Umé or “Granny.” Her husband died in his thirties. She has been a widow for fifty years. Although she was well-connected, a beauty, and productive, her health has long been in decline and she is suffering from dementia. Having outlived her daughter, she is being cared for by one of her two granddaughters in Tokyo, Senko. She and her husband are childless. They live in one of the few homes not destroyed by the war and they can afford to retain a maid. But Umé requires more and more care. Her behavior is more than the eccentric conduct of the mentally confused. She steals, she lies, and she purposefully attempts to bring shame upon her family. Itami, her grandson-in-law, rages against the old woman, calling her both a cancer and a pig, and demands that Umé must leave. Desperate, his wife orders her younger sister Ruriko to transport the old woman to the family of her sister Sachiko, whose family of four fled to the country years ago after their home was destroyed in the war. Realizing she has been out-strategized by Senko, she does what she can to find room in their cramped home for the old woman. But as her dementia worsens, she still retains the capacity to lie, cheat and steal. She exaggerates her hunger, demands extra food when every scrap is rationed, and methodically tears whatever clothing she is given into strips. Niwa is relentless in alternating between portraying Umé as a victim in need of care, an insatiable animal, and malignant cancer eating at the heart of the family. Every page is a challenge to our understanding of mercy, tolerance, duty, and love.

After a while, becoming aware that she was being observed, Umé would laugh awkwardly. Then she would turn aside and gaze into the distance as if she were quite alone. To Minobé there was something almost frightening about this instinctive movement of Umé’s. It made him think of animals who can from one moment to another disregard the human onlooker. He felt that only someone who had lived an immense number of years could effect such a strange, almost inhuman aloofness: never could it be acquired by deliberate study or imitation.” (334)

“Downtown” (1948)

By Hayashi Fumiko (f.)

Translated by Ivan Morris

Ms. Hayashi is one of the few female writers represented in this collection. She wrote often about the plight of poor women fighting to carve out a living in Tokyo. In this instance, she tells the story of Ryo, a twenty-eight-year-old woman whose husband was taken prisoner in the Russo-Japanese war. She has not seen him for six years. She is raising their son on her own in a country village when she decides to move in with a friend in a crowded Tokyo boarding house and try to make a go as a door-to-door tea vendor. One day, having had no luck at all, she comes across an iron shack in one of the many shell craters that still dot the Tokyo landscape. There she meets a kind man willing to buy some tea. She discovers that he only just returned from a Siberian prison the year before. He had been captured while cutting wood for the army. On his return, he discovered his wife had left him, so he has been living in this shack and working in scrap metal ever since. Their budding romance is exquisite, its denouement completely unexpected.

Ryo’s thoughts flew to her husband, from whom she had not heard for six years; by now he had come to seem so remote that it required an effort to remember his looks, or the once-familiar sound of his voice. She woke each morning with a feeling of emptiness and desolation. At times it seemed to Ryo that her husband had frozen into a ghost in that subarctic Siberia—a ghost, or a thin white pillar, or just a breath of frosty air. People no longer mentioned the war and she was almost embarrassed to let it be known that her husband was still a prisoner. (354)

“A Man’s Life” (1947)

By Hirabayashi Taiko (f.)

Translated by George Saito

Ms. Hirabayashi’s topic took me by surprise: a dark philosophical study of two men imprisoned for murder. The primary narrator is a gang member who is sentenced to ten years for murdering his boss. The police believed the narrator’s motive was to take control of the gang, but the truth is that he stabbed the man out of jealousy. It was well within the narrator’s rights to appeal the sentencing and argue that it was a crime of passion, but he was so morbidly depressed over his failure to win the love of the girl of his dreams that he takes the ten years simply to spite himself. After a year in solitary, the narrator is moved to a four-man cell run by a man who is on death row for murder and rape. As the narrator studies the man who wakes each day knowing that he could die, he comes to a deeper understanding of “conversion,” coming to believe that the justice system can help a man truly develop a higher sense of responsibility, honor, and integrity.

“I slept little better that night. Occasionally, he’d roll over and kick me. I’d awake with a start, as if dashed with cold water. Even if he’d forgiven me, he hardly needed a pretext to commit another murder. It was I, close at hand, who had the greatest chance of becoming a victim.” (381)

“The Idiot” (1946)

By Sakaguchi, Ango (m.)

Translated by George Saito

Mr. Sakaguchi’s tale portrays the collapse of civilization and morality in the final months of World War II. The great city of Tokyo is reduced to a shantytown populated by beggars, prostitutes, and thieves. Izawa lives as a boarder in a room formerly occupied by the son of a husband and wife who has a tailoring shop on the first floor. Their son recently died of tuberculosis; if the room were not already unhygienic enough, Izawa shares his living quarters with “a pig, a hog, a hen, and a duck” (385). The owner’s daughter lives up in the attic in a kind of exile. She is unmarried and pregnant. At least eight of her paramours have pooled their money to provide money for the unwed mother, but soon after they agree to provide this monthly support a bean curd salesman finds his way into the daughter’s bed, causing the five to terminate their offer of aid. Five prostitutes live on the other side, a man who boasts he was a murderer, and a woman who is supposedly someone’s mistress. The daughter of the woman across the way was sold in marriage to a man almost sixty: she took rat poison and died. Izawa was trained as a reporter but soon joined an enterprise making cheap war propaganda films. He fancies himself an artist and above all the animalistic behavior he sees around him, but one night during an air raid he begins perhaps the most morally reprehensible relationship of all the people struggling to live in the shadow of the allied bombing: he takes up with a woman who is mentally disabled, a “feeble-minded woman” whose body is always “awake.” Izawa recognizes that he is a hypocrite, yet comes to the heinous decision that in order to avoid the discovery of his shame, he must murder the woman during the next bombing run.

“When it came to the question of what the woman was thinking about when awake, Izawa realized that her mind was a void. A coma of the mind combined with a vitality of the flesh—that was the sum and total of this woman. Even when she was awake, her mind slept; and even when she was asleep, her body was awake. Nothing existed in her but a sort of unconscious lust.” (403)

“Shotgun” (1949)

By Inoué Yasushi (m.)

Translated by George Saito

“Shotgun” is a masterpiece. Mr. Inoué’s narrator is a dedicated and “pure” poet. As so often happens, he is in need of money. A chance meeting with a former high-school friend leads to an offer: the man promises that if the poet will write a poem on the art of hunting, he will buy it and publish it in the next issue of his hunting magazine. The poet, who has no experience at all with hunting and who holds the “sport” in disregard, agrees. Weeks later, he composes a prose poem based upon a memory of his from years before when he watched a hunter crossing a snowy field, a shotgun slung across his back. The narrator shares the poem with us so that we can properly understand the poem’s meaning. Confident that we readers have understood the tone of the poem, he acknowledges his embarrassment that he submitted the poem at all. In fact, it painted hunting in such a dismal light that he regrets sending it to his old friend and imagines that the poor man probably was too embarrassed not to print it. For the poet, the hunter and the shotgun were really symbols of man’s isolation and loneliness. For weeks after the magazine’s publication, the poet imagines that he will receive many letters of complaint from the magazine subscribers. Yet no one writes, until a few months later a man contacts him not only to praise him for his depiction of the hunter but to identify himself as the man in the poem. In order to fully explain himself and to make clear to the poet the state of his mind that snowy day, he asks the poet to read three letters included in a bulky envelope.

You may find it strange of me to mention that I have three letters. I meant to burn them. I am very sorry to bother you, but may I ask you, at your leisure, to look at the three letters I am sending under separate cover? I would like to have you understand what you called “the white river bed.” Man is a foolish creature who wants above all to have others know about him. I myself had never harbored such a desire until I learned that you had shown a special interest in me.” (422)

“Tiger-Poet” (1942)

By Nakajima Ton (m.)

Translated by Ivan Morris

In a reversal of many Chinese short stories where a common trope is the bitter youth who has failed his exams, Mr. Nakajima’s story tells the story of a man who stood at the top of his class in his civil service exam but who found his subsequent career burdensome and unrewarding. As it happens, he dreams of becoming a great poet. Despite being at the height of his bureaucratic arc and being responsible for a family of four, he retires early and takes up residence in the country. There, he discovers the tremendous difficulty of making a living as a poet; worse, he watches in envy as lesser men rise in rank in government offices. His bitterness works a terrible transformation on him, changing his life forever.

“Alas,” answered the voice, I am hideously disfigured! For very shame I cannot let you look at me in my present form. I know that just to glance at me will fill you with horror and disgust. Yet now that we have met so strangely, I pray you to stay and talk, even though we are unable to see each other.” (458)

“The Courtesy Call” (1946)

By Dazai Osamu (m.)

Translated by Ivan Morris

Mr. Dazai, a nihilist, presents a snapshot of daily life in the ruins of post-war Japan. To bring his story to life, he indulges in the darkest of black humor. As is often the case, the narrator is Dazai himself. His Tokyo residence destroyed, he and his wife have been living in the country. One afternoon, a Mr. Hirata appears at his door. He claims that he is Dazai’s friend from grade school and that he has come to try to convince Dazai to organize a reunion. As Hirata envisions it, the celebration will involve twenty men and ten gallons of sake. For the life of him, Dazai cannot remember this “friend,” but the guest continues to badger his host until Dazai feels driven to stand up for himself.

“The man continued drinking and as the level of the whisky in the second bottle began to sink, I finally felt anger rise within me. It’s not that I was usually jealous about my property. Far from it. Having lost almost all my possessions in the bombings, what was left meant hardly anything to me.” (471)

“The Priest and His Love” (1954)

Mishima Yukio (m.)

Translated by Ivan Morris

As in Kikuchi’s “On the Conduct of Lord Tadanao,” Mr. Mishima develops a minor story from Japan’s medieval literature in order to illustrate an eternal dilemma. In this instance, Mishima weighs the elements of spiritual and physical desire. The story is set within the context of Enshin’s Pure Land Buddhism, a branch of Buddhism unique to Japan. The Great Priest of Shiga Temple has grown old in his contemplation of the complex cosmology of religious texts. He has abjured all contact with women and virtually left the world of desire behind. That all changes when he happens to catch the glance of the Great Imperial Concubine. The accident throws both the holy man and the beautiful woman into turmoil.

“So far as his body was concerned, one might say that the priest had well nigh been deserted by his own flesh. On such occasions as he observed it—when taking a bath, for instance—he would rejoice to see how his protruding bones were precariously covered by his withered skin. Now that his body had reached this stage, he felt that he could come to terms with it, as if it belonged to someone else.” (489)