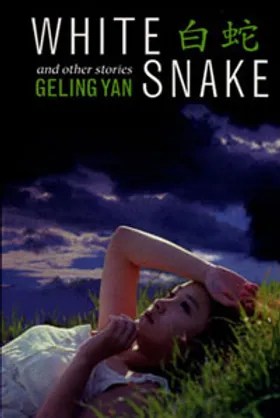

White Snake and Other Stories

By Geling Yan

Translated by Lawrence A. Walker

(1996, trans. 1999)

Aunt Lute Books

(Short Story Collection)

Geling Yan is a successful novelist and screenwriter. She wrote the screenplay for the film adaptation of her short story, “Celestial Bath,” which became Xiu Xiu, The Sent Down Girl. Her novella Thirteen Flowers of Nanjing and novel The Criminal Lu Yanshi were adapted by director Zhang Yimou as Flowers of War (2011) and Coming Home (2014).

“White Snake”

Ms. Geling tells the story of a dancer who became legendary for her performance as the White Snake in the eponymous ballet, a complex story of desire, magic, and love. The ballet, inspired by one version of the popular and widespread folktale of White Snake and Blue Snake, relates how, when the male Blue Snake proposed to the female White Snake, the latter answered that they should first fight a battle. If Blue Snake should win, White Snake will marry him. However, if White Snake defeats Blue Snake, Blue Snake will become female. Impassioned, Blue Snake agrees to the conditions of the wager. The two battle ferociously, and in the end, White Snake defeats Blue Snake. Blue Snake becomes a female snake and the two live in peace until White Snake falls in love with a human man, Xu Xian. Blue Snake is consumed by jealousy. She tells Xu Xian that he is bewitched and that the woman he loves is actually a snake goddess. He refuses to believe her claim, so Blue Snake gives him a potion to allow him to see his beloved in her true form. The shock of his discovery causes Xu Xian to die. Grief-stricken, White Snake embarks on a series of adventures to retrieve the ingredients necessary to concoct an elixir. On her return, she does Xu Xian and dances around his corpse until she restores him to life. Aware of her true identity, Xu Xian flees to the sanctuary of a monastery. When the abbot refuses to hand over her lover, White Snake attacks and destroys the temple with invincible strength, which causes the abbot to realize she must be pregnant. White Snake returns with her captive lover who intends to flee as soon as White Snake delivers their baby. Meanwhile, Blue Snake, still enraged by jealousy, attempts to kill Xu Xian with a magical sword. White Snake prevents the murder. Eventually, the two female snakes renew their alliance and all parties flee to a mountain paradise. In the short story, Sun Likun becomes a star for her uncanny ability to bring to life the character of White Snake. She is a darling of the Revolution and gathers international fame when she is sent to perform in Moscow. Between 1956 and 1961 her name is a buzzword for beauty and Chinese excellence. In 1962, as part of the Cultural Revolution, she is denounced, forced to endure countless interrogations, and required to write a four-hundred-page self-criticism. She is accused of both immoral sexual conduct and being a political spy, and she is imprisoned in a derelict theater in a remote backwater. The story begins there, following her through a series of transformations, reversals, and escapes that seem both remarkable and predictable given the culture and political history she inhabits.

“When she finally stepped out of the corner and walked onto the stage again, she was completely transformed. A mysterious change had taken place in that darkness. She was still wearing the sea-blue sweater, its sleeves a tangle of unraveled threads. It still stretched grotesquely across her bosom, which had long since spread out abundantly. She was still wearing that same pair of pants with the part around the knees protruding forward as if she were eternally kneeling. Yet she was a completely different person from before her hasty exit. That chin of hers, now thick and broad, once again floated freely, drawing exquisite arcs in the air.” (20)

“Celestial Bath”

This story is set in the last years of the Cultural Revolution. Teenaged Wen Xiu is a sent-down girl, an intellectual rusticated from Chengdu to a remote region of the Sichuan Province near the Tibetan border. According to her orders, she is to spend six months learning to herd horses and prepare them for use by the Chinese Army. This will require her to leave the safety of the camp at the Livestock Bureau and head deeper into the wilds where she will be trained by a Tibetan man, known only as Lao Jin (Old Jin). Wen Xiu objects to the orders; as a young woman, she has no intention of sharing a tent in the middle of nowhere with an uncivilized man in his forties. Her superior explains that she has nothing to fear: as a consequence of a tribal conflict many years ago, Lao Jin was castrated. Many girls have gone out to be trained by Lao Jin before and not one has complained of any untoward conduct. As the months wear on, Wen Xiu begins to trust the old man. Though Lao Jin does not bathe, he understands that as a city girl, Wen Xiu craves cleanliness and provides an ingenious bath for her. Unfortunately, when her six-month contract is complete, Wen Xiu realizes that the cadres in the Livestock Bureau have forgotten her, and while all of the girls at the bureau have been sent back to Chengdu, she has no official orders, identity, or card granting her the right to live in the city of her birth. In 1989, the short story was turned into a successful feature film called Xiu-Xiu, the Sent Down Girl. Joan Chen directed the film and co-wrote the screenplay with Geling Yan. Though banned in China for its sexual content and criticism of the Communist Party, Chen was awarded Taiwan’s Golden Horse award and Berlin’s Golden Bear.

“If you didn’t know his story, you couldn’t tell that Lao Jin lacked anything that other men had. Especially when Lao Jin lassoed a horse. His whole body formed an unbroken arc with the rope, taut as a bowstring. Once the horse straightened his legs to run, Lao Jin had him.” (61)

“The Death of the Lieutenant”

The story takes place in a military camp, focusing on twenty-five-year-old Platoon Leader Lieutenant Liu Liangku. In many respects, Liu’s is a success story. He comes from generations of peasants; his starving family sends him off to the army, where he quickly puts on muscle and progresses through the ranks. He enjoys steady meals, power, and the ability to send money back to his family in Ding Province. He also has a woman, Momo, whom he hopes to marry. There is pressure, though. Another man, a dealer in rabbits which are to be raised for eating, has designs on Momo, and unlike Liu, he is not linked to an impoverished family he must support for the rest of his life. When his pay is readjusted to compensate for advances he used in the last year to send home, Liu becomes desperate to lay his hands on ready cash and commits a theft that goes wildly wrong. The story is compelling in its own right, but Geling pushes the piece into an altogether unexpected sphere when the female observer at Liu’s trial is neither his lover nor his mother, but a writer who is covering the trial.

“It was at that moment that the lieutenant discovered Momo’s face had become unfamiliar–flatter and wider than the face he knew with a yellow nose tip. This was because seeping sweat had washed off all the powder. And when did Momo learn to apply face powder? After coming to Beijing? From Youhui, the base commander’s wife, who works in the barbershop?” (92)

“Red Apples”

As in “Celestial Bath,” this story is set in Sicheng Province on the Tibetan border. The story is told from the perspective of one of a group of women who are part of a troupe of traveling soldier/actors. After weeks of being on the road, they are headed to a popular way station that features hot springs. On the way, they stop to pick up a young Tibetan woman who appears to make her living by selling apples. Geling showcases the culture clash between the Chinese soldiers and the local Tibetans, the Chinese appropriation and “improvement” of the springs, and the privileges afforded to high-ranking cadres compared to Chinese soldiers and the indigenous peoples. As in “Celestial Bath,” the bath is a metaphor for purity and the bankrupt morality of the Chinese hegemony inspires who will be washed in the purest waters. The story also features a scapegoat, the “man from Gansu,” who dresses in rags and does menial labor at the way station. He had been disciplined the year before for spending too much time leering at the bathing Tibetan women. He was sent home to a region that was suffering a famine brought on by the Chinese policy of the Great Leap Forward, a national tragedy falsely attributed to “natural disasters” between 1959 and 1961. The man’s entire family died and he was the only surviving member of his town; the Chinese soldiers derive sadistic pleasure in abusing him for his backward nature and emaciated body. Incidentally, the author became a member of the Chinese Liberation Army at twelve years of age and served in a ballet and folk dancing troupe.

“The way station spared no effort to get along with the Tibetans. In other locales, the Han Chinese oppression had given the Tibetans cause to revolt, and this isolated place had felt the repercussions. Even in peaceful times, the Tibetans, who were the way station’s only source of fresh meat, would bring beef and mutton that had started to turn and proffer it to the way station as a gift. If the way station had preferred any steamed bread with too much or too little sourdough, it would give this to the Tibetans in return.” (116)

“Nothing More Than Male and Female”

Yu Chuan is a young woman from the provinces who is studying to be a nurse. She takes up residence in the small home of the parents of her fiance, Cai Yao, an editor in a small publishing house. He is living at home with his mother and father as well as a younger sister, Xiaoping, anxiously awaiting the moment he is awarded an apartment by the local housing bureau. There is also a mysterious “fifth brother,” Lao Wu, who lives in a small closet-like space within the crowded house. Lau Wu is sickly; when he was born he suffered kidney failure; it was predicted he would never live and certainly never have a wife. He survives on a meager diet. The crawl space where he lives smells of medicine and is dominated by books and a catheter. This secret son is six feet tall, exceedingly pale, and exquisitely beautiful, looking and moving more like a woman than a man. This wraith-like figure who comes and goes at mysterious intervals affects the family in remarkable ways, although more often than not he is silent, away, or locked in his closet. Yu Chan develops a strong interest in this curious being, partly because of his physical beauty and partly because since he never knows when he might drop dead, he has set himself a variety of artistic goals, such as publishing a study of rare petrographs or becoming an artist. She also grows weary of Cai Yao’s rushed and rough furtive love-making and his lack of kindness and empathy. Meanwhile, his mysterious brother looks on, perhaps tempted, perhaps simply curious, as he continues to live somewhere between life and death.

“While they were walking upstairs, they ran into Lao Wu coming downstairs. Lao was wearing a maroon stocking cap, and the cap had pressed some of his hair to each side of his eyebrows, making him look even more like a girl. Seeing the two of them, he raised his eyes slightly, his eyelids revealing two deep folds as if he were fatigued or emaciated.” (127)

“Siao Yu”

Siao Yu is a young woman who, through dint of self-discipline and focus, became a nurse in China at seventeen. She had a brief dalliance with a former champion swimmer; he found her desirable and sexually available, and she was amenable. But he disappears for six months without so much as a word. Then out of the blue, he sends her his plan: she will take the money he has sent her, fly to Sydney, Australia, and pay a broker fifteen-hundred dollars to set up a sham marriage in order for her to gain citizenship. He will follow. Her friends arrange a wedding party at the city court, she is asked to describe the private parts of her fiance, documents are signed, and she is legally married to a sixty-seven-year-old Italian man with a drinking problem and a fifty-year-old lover. Inspectors visit their lodgings to assure the legitimacy of their relationship, the swimmer, Jiang Wei hunts for work, and Siao Wu attends classes to earn an Australian nursing degree. The standard scheme requires the woman to live with her “husband” for one year, at the end of which time she files for divorce and lives her life freely. The problem is that neither the tempestuous Rita, who alternately battles and makes love to the old man, nor the muscular athlete, Jiang Wei, can comprehend the quiet, understated relationship that develops between the young nurse and the old man. Jiang Wei is particularly affected: he is overwhelmed by jealousy and constantly accuses Saio Yu of behaving indecently with the old man, while Rita comes to believe that the old man has fallen for the young nurse, who, in truth only treats the old man with common decency.

“Beasts don’t marry each other. There’s no need. They just breed together, that’s all! I’ve got to find a man that, when you’re together with him, you don’t feel like some she-beast. It’s strange: being with a human, a beast starts to be like a human; being with a beast, a human becomes like a beast!” (174)