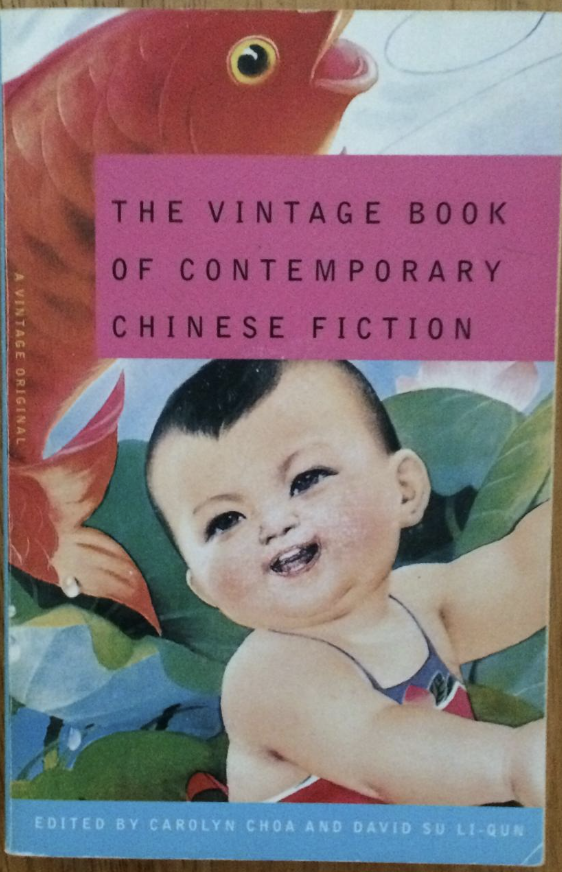

The Vintage Book of Contemporary Chinese Fiction (1998)

Edited by Caroline Choa and David Su Li-Qun

(Short Story Anthology)

Vintage

“Beijing Opera” (1998)

By Su Li-Qun, David (m)

Translated by Carolyn Choa

Mr. Su turns the tables in this study on what it means to be Chinese. The protagonist is Miss Jane. Her father is a powerful Chinese, and her mother is a member of the British aristocracy. Jane and her brother Stephen were raised in China, but Stephen went off to study Philosophy, Politics, and Economics at Oxford. He earned a Master’s degree in Chinese History, worked as the China Consultant for a British Bank, and will soon be returning to China to serve as the second-in-command at the British Embassy in Beijing. Meanwhile, blond-haired and blue-eyed Jane has decided to pursue a career in Chinese Opera. Her guardian is convinced that the Chinese will reject her outright because she is a “foreigner.” Miss Jane argues that she has already performed male roles in make-up; surely she will be accepted.

“I haven’t made a scroll this big in years, let alone attempted a single character! It is common knowledge that the fewer strokes there are the more difficult the task. In this way calligraphy is comparable to building a house—the less material at one’s fingertips, the harder it is to construct a frame. Without a solid structure, all the skill of execution is in the spirit! (6)

“Hong TaiTai” (1989, translation 1998)

By Cheng Nai-shan (f.)

Translated by Janice Wickeri

Ms. Cheng’s piece is a brief (ten pages) and moving portrait of a beautiful “second wife” who weathers not only the death of her “husband” but also the political storms that rage over Shanghai from the 1950s to the 1980s. She survives “the three hard years of Natural Calamities”–the three years of famine brought on by Mao’s “Great Leap Forward” between 1959 and 1961–and “the tempest” of the Cultural Revolution that lasted from 1966 to 1976. Her servant and her husband save their mistress’s life by allowing Hong Taitai to adopt them as her children, thus certifying Hong’s bona fides as a proletarian. She also manages to preserve a mirror, a symbol of her remarkable beauty, by covering much of it with pictures of Mao and other party officials—this was the only way mirrors could be preserved during this period. This would make an excellent addition to a study of China in the 1950s through the 1980s.

“’Hong Taitai will suffer now! This is really difficult for her.’ The other mourners commented surreptitiously among themselves. Yes, Mr. Hong was a man among men. But was he willing to entrust the family property to Hong Taitai? Naturally, it was safer with his wife. With him gone, Hong Tatai is left with nothing, not even a last word. It’s hard for her.’” (16)

“Fate”

By Shi Tie-sheng

Translated by Michael S. Duke

Mr. Shi is a teacher who was “sent down” to the countryside for reeducation in 1969 during the Cultural Revolution. In 1973 he was crippled in an accident and has lived his life in a wheelchair. In this story from 1991, Shi speaks in the voice of a successful student on the eve of his departure for the United States, where he plans to complete his doctorate and return home to help reform Chinese education. A twist of fate, a bicycle accident, robs him of his future. His front wheel strikes an eggplant in the road and a taxi strikes him, rendering him a paraplegic. Bedridden, and raging, he analyzes the accident over and over again. What was it that caused his personal catastrophe? Was it the cabbie? The eggplant? The friend he stopped to talk to on his ride home? Or was the cause of all his suffering the student who laughed at him in class that day? Shi’s answer is at once absurd and a brilliant piece of political criticism.

“Although I did not get off my bike, I did squeeze the brakes while I was talking, no doubt about it, I did squeeze the brakes a little. How much time did I lose squeezing the brakes? One to five seconds. Right, if I had not wasted one to five seconds talking to him, then I would have run over that aubergine one to five seconds sooner. Of course, of course, the aubergine would no doubt have caused my bike wheels to swerve to the left and I would have sprawled out in the middle of the road as before, but everything that happened later would have been changed.” (32)

“Life in a Small Courtyard” (1988)

By Wang An-yi (f.)

Translated by Hu Zihui

Ms. Wang is the daughter of the famous woman writer Ru Zhi-Juan. Like many Chinese, Ms. Wang’s education was disrupted by the Cultural Revolution. Likewise, the characters in “Life in a Small Courtyard” find their lives uprooted by circumstances beyond their control. Members of the Municipal Song and Dance Ensemble have just had their housing reallocated and they are in the process of figuring out how the new units will be parceled out. Not surprisingly, the most well-connected couple, Huang Jian and Li Xuwen have been awarded the prize apartment: the former office of the dance ensemble; Huang is the son of the Cultural Bureau. Ms. Wang speaks through the voice of Song Song, the wife of A’ping. She is acutely aware of the way each of the couples struggle with the challenge of marriage: the couple that battles over money, the husband who salves the depression of his wife with periodic gifts, the gossips, and the newlyweds. She and A’ping are also struggling, and when they receive notice that they must go on tour just two weeks after getting home for the first time in months, she loses her temper with A’ping. He disappeared hours ago. Where could he have gone?

“A’ping held my hands tenderly. Though I had worn two pairs of gloves, my hands were still cold. He put them into the pockets of his overcoat. I drew them out at once. I didn’t want such tenderness. What I badly needed was a stable family life, not embraces and kisses! (52)

“Between Themselves”

By Wang An-yi (f.)

Translated by Gladys Yang

Ms. Wang focuses on the parallel stories of two “orphans.” Wang Qianging is a schoolboy with a ferocious appetite and a nose for trouble. As his mother died shortly after he was born, he is being raised by his grandfather. True, Wang’s father is still alive, but his new wife refuses to allow him to spend even a penny on his child. Teacher Zhang is in his thirties. One day his principal calls Zhang to his office. With some ceremony, the principal presents Zhang with a document confirming that his father, who had been labelled a Rightist in 1957 and died on a farm in Yancheng, has been officially cleared of his crimes. As a result, Teacher Zhang’s files will be updated and his status will also be cleared; from this moment on he will no longer carry the stain of his father’s crime. Teacher Zhang is unmoved by this development; he has absolutely no memories of his father. As it happens, the two orphans are drawn to one another. Can they support one another? Wang An-yi is also the author of the novel Fu Ping.

“Bicycles sounding their bells shuttled in an out of the lane, a two-way lane used as a thoroughfare. It was lined with smart modern houses, but at one end people had built many shacks. None of these had gas installed, so firewood crackled and smoke belched as they lit their stoves. A boy seated in front of one smoky pot was eating pot stickers. First he ate the pastry, keeping back the meat stuffing. He put those pitifully small meatballs in the bottom of a large bowl, then ate them one by one.” (63)

“Between Life and Death”

Su Shu-yang (m.)

Translated by Carolyn Choa

Mr. Su presents us with a charming monologue delivered by a man with a unique profession: he prepares the dead for cremation. As such, he is taboo. And so, though he has fond memories of his first love, he is philosophical about her decision to reject him as a suitor. They would have made an interesting pair, as she was a beautiful trash collector and he was a philosophical death worker. They parted. She became a movie star. Later, our hero becomes the acquaintance of a woman who is a gynecologist. She struggles with her love for the hero while also dreading what people might say of her if she married such a man. Eventually, though, love finds a way.

“You see, a person’s fortunes are often determined in the spur of a moment–the very moment she was invited to star in a movie she changed completely—from a poor girl who earned her keep collecting rubbish into a glittering movie star. As for me, it only took a moment as well, not much longer, to make the decision to become a man who burns dead bodies for a living. In that split second, I toppled from the fairly respectable position of an educated man to being the scum of the earth, undeserving of literature, art, or philosophy.” (86)

“Cherry” (1996, translated 1998)

By Su Tong (m.)

Translated by Carolyn Choa

Su presents us with the ever-pragmatic postman, Yin Shu, who becomes caught up in a traditional romantic ghost story. One fall day while delivering mail to Maple Wood hospital at the top of Maple Wood Road, Yin Shu encounters a beautiful young woman dressed in a white gown. She introduces herself as White Cherry and asks if the postman has any letters for her. He does not, but after encountering her every day for a week, he begins to volunteer at the post office in order to search for letters to the young girl with jade fingers. The short story reads like a 19th-century British Christmas tale, though the Chinese locale and subtle symbolism suggest the ghosts that haunt this hospital may be the innocent victims of China’s regular political upheavals.

“Everything about Yin Shu is slow and meticulous. His physical appearance matches his personality perfectly—there is no flesh on his spare bones anywhere. His colleagues at the post office regard him as something of a weirdo. He only speaks when absolutely necessary—otherwise his cool gaze holds everyone at bay, forestalling any possibility for idle chitchat.” (98)

“Young Muo” (1996, translated 1998)

By Su Tong (m.)

Translated by Carolyn Choa

Su tells the story of the esteemed Old Muo, a master of traditional Chinese medicine and his ne-er-do-well son, Young Muo. Though a short story, Young Muo’s adventures are certainly picaresque. One afternoon the lovely young Shi-feng arrives at the home of Old Muo to petition for the master’s aid with her old husband’s stomach pain. Young Muo, an ignorant idler, decides to impersonate his father. For her part, Shi-feng is too panicked to see through Young Muo’s pretense and utter lack of his father’s medical knowledge. Nevertheless, after accidentally giving the old man a powerful diarrhea-inducing prescription, Young Muo succeeds in curing his patient. He continues to seek out young Shi-feng, who hints that her husband may now be suffering from sexual dysfunction. This kicks off a reckless affair between the two, and when the old man sends some hired thugs to exact retribution, they of course attack Old Muo. The topic of the young quack doctor and the venerable practitioner of traditional Chinese medicine is not only comical but also political. Mao himself promoted traditional Chinese medicine, partly as a way to counterbalance the shortage of doctors trained in Western Medicine. Although he promised that each commune would have sufficient “barefoot doctors” to care for the proletariat, Mao did not believe in traditional medicine. This story might be paired with Lu Xun’s heartbreaking short story about the failure of traditional cures in his short story “Medicine.” Young Muo” also highlights the selfishness and dissolution of the younger generation and shines a light on how citizen’s sued for justice in remote regions where laws were more medieval than modern.

“At first nobody on Cedar Street was aware of Young Muo’s house calls on behalf of his father. The tomfoolery had, by accident, ended rather well, as was often the case in life. Young Muo was well-known on Cedar Street for his dissolute behavior, and indeed he forgot about the whole incident. Furthermore, he was certain his father had no inkling of what he had done. Young Muo continued to revel in chess, swimming, loitering in streets, sticking his head into gatherings of girls, and generally fooling around.” (114)

“The Window” (1978, translation 1998)

By Mo Shen (m.)

Translated by Kwang Wendong

Perhaps you know of Comrade Lei Feng, a humble, loyal, and selfless embodiment of the spirit of the Communist Revolution? He may have been based on a real soldier, but it is far more likely that he was a propagandistic device. Mr. Mo introduces us to another superhero of Mao Zedong thought: the resourceful government bureaucrat, Miss Han Yunan. We first encounter her in the 1970s as she offers advice to travelers on a train, providing information for her fellow comrades from her vast knowledge of memorized train and bus schedules. Two travelers heading to a mass emulation efficiency drive discover that in her three years of service, she has used her passion for Mao Zedong thought and a devotion to serving her customers to learn the lengths, stations, and departure and arrival for all train and bus routes throughout China. She acknowledges that at first she was frustrated by the ignorance and impatience of the travelers she served. Over time, she determines to reshape her attitude to service. An important moment occurs early on. After wondering at the boorishness and slow-wittedness of many of her clients, she leaves her booth and tries to buy a ticket herself. Once on the other side of the window, she has an epiphany: the booth is quiet, but in the din of the station, it is almost impossible for the travelers to hear the ticket sellers. She also notices that depending on which of the two-hundred and sixty-two dialects the traveler speaks, station names often seem similar. She makes up cards to help these travelers, assists them as they plan complex connections, and sends them on their way quickly. She becomes a model of the communist spirit, but then in 1976 the Gang of Four takes power and the first large character poster appears in the station denouncing Secretary Lei, whom Han Yunan respected. When she applies for membership to the Youth League, the bureaucrats ignore her extraordinary service and criticize her for attempting to become a “bourgeoisie specialist.” They link the girl to her mentor, Secretary Lei, calling them both “capitalist roaders.” Each is passionate in their enthusiasm to serve the people, though Lei understands that in the shifting political winds, young Han is putting herself in jeopardy by continuing to excel at her devotion to serving China’s travelers.

“Wiping my eyes with my handkerchief, I was about to answer when a voice called for Secretary Lei from outside the door. It was young Zhu. She must have overheard our conversation. Racing into the room, she grasped Lei’s hand as tears flowed down her cheeks. Then she suddenly turned and rushed towards me saying: ‘Sister Han, I want to be an ox for the people too.’

Hugging each other, we both wept.”

“The Lovesick Crow and Other Fables” (1989, translation 1998)

By Wang Meng (m.)

Translated by Denis C. Mair

Mr. Wang was born into a family of educators and writers. Between 1958 and 1962 he was compelled to be a laborer in a suburb of Beijing. In 1963 he was exiled to Tibet for ten years. After that, he was allowed to work as a translator in the Uygur community at Urumqi. Perhaps this sharp-tongued collection of fables full of incomprehensible twists and unsatisfying resolutions comes from this period in his life. The stories include “The Discommoded Frog,” “Boiled Eggs and Radio Calisthenics,” “The Thousand Li Horse in its Dragon Lair,” “I Am One of Your Kind,” “Pretty at First,” “The Singer Who Always Won the Day,” “Comedy of the Ducks,” “After Becoming a Swan,” “Lovelorn Sister Crow,” and “A Story I Heard.”

“The Red Army men wore straw sandals during the 25,000 Li March, They didn’t have the chance to go to Wangfujing to buy high-heeled leather shoes. The quality of a woman’s shoes is not as important as her gauze mask. A snow-white mask shows that a woman is civilized, sanitary, thoughtful, concerned for other people, discerning, well-provided for, modern, informed about science, modest, optimistic, judicious, objective, self-restrained, and cautious. And what does a good pair of shoes show? It is a sure sign that a woman is banal, superficial, free with money, pretentious, fake, and flirtatious.” (from “Pretty at First”)

“The General and the Small Town” (1979)

By Chen Shi-Xu (m.)

Translated by Anonymous

Mr. Chen tells the story of a quiet country backwater forever changed when a report arrives that a great general will be retiring there. It turns out that he has been sent down as a renegade. Nevertheless, the townspeople are generally pleased to have a person of such notoriety as a neighbor. He and his wife set up a home on top of old Ringworm Hill, a rocky outcropping believed to be the site of a common burial from centuries before. Despite his “renegade” title, the general soon proves he has an exemplary revolutionary spirit. He prepares Ringworm Hill for planting pine trees: he intends to turn the eyesore into a park for the young lovers of the town. He advises the people how to improve its roads, manage the treatment of waste, and rework two small streams to increase water flow and cleanliness. Most importantly, when waiting to be treated at a hospital, he takes the side of a desperate mother who has a child with a high fever. He causes a terrible scene and ensures that the child will be taken care of before he is. In 1976, the word is sent down that the general has been cleared of his renegade status. Immediately, the people fear that he will leave their town for a great city. Then, Premier Zhou Enlai dies. Word from the city arrives: no one must mourn for him. That morning, the old general arrives, dressed in his military uniform and wearing a black armband. He and the tailor have stayed up all night assembling the armbands. He urges the people to celebrate the great hero of the revolution. Swayed by his example, the town mourns. A party member reports the crime and within a few days, word arrives that the general is once again returned to “renegade” status.

“Gradually, people got used to him standing there, like a bronze statue. He became like the coppersmiths, cobblers, and tinkers at the corners of the crossroads. If you didn’t see one of them for a few days, you would feel there was something missing.” (199)

“Black Walls” (1982, translation 1998)

By Liu Xin-wu

Translated by Alice Childs

In “Black Walls,” Liu introduces us to the quiet citizen Zhou. He is in his thirties, he lives alone, and he has never married. He was sent down to the countryside seven years ago. He is a pleasant enough person but an unknown quantity: no one knows enough about him to decide whether they like him or hate him. One morning he rises early and moves all of his furniture out of his house. He collects water in a large basin and begins mixing powders. Passers-by ask him if he is painting his house. He replies affirmatively, and when they politely ask him if he needs any help, he informs them that he believes the job will be manageable as he has borrowed a manual pump sprayer. Moments later, a whisper campaign runs through the town: Mr. Zhou is painting the interior of his house black—both walls and ceilings! The town is in an uproar. Had this occurred ten years before, they could have rallied the thugs who once passed for policemen to defame him and run him out of town. But now, what can they do? And how will his transgression stain the reputation of the town?

“’Chi – chi – chi…’ The noise from the spray gun continued. Looking toward the room all they could see was blackness. No one really believed Mrs. Li’s explanation. The more Li looked, the more she could not help despairing. What could one say? Black walls! In this very courtyard! Mr. Zhou is not afraid of doing evil things himself, but he should not get others involved.” (177)

“Big Chan” (1998)

By Wang Ceng-qi (m.)

Translated by Peng Wen Lan and Carolyn Choa

Wang was a student of Shen Congwen, author of the novel Border Town. “Big Chan” appears to be the narrator’s recollections of grade school, but it quickly turns into a set of character studies, and then–quite suddenly—a forbidden romance. It breaks up as quickly as it begins, a victim of a bit of bureaucratic shuffling. Disarmingly frank and simple, it may also be a study in contrasts between the classical period and the modern, as the two lovers communicate their desires through their reading of classic romances like The Dream of the Red Chamber, Tragic Love Stories, and Life Among the Floating World. If their actual affair is more prosaic and short lived, so be it!

“What else did he do? … Now and again [Big Chan] helped copy exam papers, operating the mimeograph roller while one of the teachers turned the pages. When they were all done, Big Chan put a match to the stencil. The odour of the burning ink floated out of the windows so that sometimes you could smell it in the classroom.” (184)

“Han the Forger” (1981, translated 1998)

By Deng You-mei (m.)

Translated by Song Shouquan

Deng tells of a complex battle of wits involving two friendly antique experts and a conniving newspaper reporter. This is a frame story, told from the perspective of old Gan, who is searching high and low for Han, who disappeared sometime during the Cultural Revolution. Long ago, during the Japanese occupation, Gan had playfully used a piece of Song Dynasty paper and his artistic skills to create a painting in the style of Zhang Zeduan. When the newspaper reporter Na Wu sees the result, he urges Gan to play a prank on Han: let’s see if we can dupe the old forger! Na Wu hires another artist to forge and affix royal seals from the Qing Dynasty to the painting and frames it. Then, posing as a dissolute Manchu, he succeeds in pawning the piece at Han’s shop. Gan immediately regrets his involvement and wants to take the painting back. Na Wu, however, is cold-blooded: he wants Han to suffer. But though rivals, Gan and Han were good companions. They shared a genuine love of Chinese opera. Does Han know that Gan is the forger? Will Han be able to avoid the traps Na Wu has set for him? At the end of the Cultural Revolution, Gan is able to restore his reputation and work again. He has the opportunity to speak on behalf of old Han, but fearing that helping his old friend might put his own status at risk, Gan remains silent. As the dawn of modernization arrives, Gan discovers he cannot stop thinking about his fellow antique expert and operagoer, and he goes on a journey to try to put things right between them.

“But Han said calmly, ‘Tell him the painting he pawned is a fake and that he should be content with the sum he got from me. If not, I’ll take him to court.’

‘I’m sorry sir. But you can’t speak to a customer that way. He came here to redeem his pledge and even if the pledge was a piece of toilet paper, we are still supposed to return it to him. If we can’t, then we should pay him twice the loan. Even f we do, I’m not sure he’ll take it. How can I tell him we’ll go to court?’ (197)

“Love Must Not Be Forgotten” (1982, translated 1998)

By Zhang Jie (f.)

Translated by Gladys Young

Zhang presents a stunningly beautiful piece about love and marriage in the People’s Republic of China. The narrator is a thirty-year-old woman who is struggling to convince herself that she is ready to marry Qiao Lin, a classically handsome man who appears to have the emotional depth of a slab of concrete. She had always sought love advice from her widowed mother, but the narrator is alone now, so she shares her mother’s advice and experience with us. Bluntly, her mother told the narrator that she never loved her husband. She advises the narrator to avoid marriage until she can find just the right man for her. The widow lives a lonely life. She reads nightly from a collection of the works of Chekhov, walks a bit in the night air, apparently talking to herself, and never remarries. After her mother’s death, her daughter discovers her mother’s diary, a collection of ordinary and philosophical writings about and to an unnamed lover. With these clues, the narrator connects the Chekhov collection and the man in the diary to a man who once acknowledged her mother at an official concert in 1961. He arrived at the venue in a chauffeured black limousine. His hair was brilliant white and when he took her mother’s hand, she trembled. Who was this powerful personage and what was their relationship? Had the party brought them together or torn them apart?

“No wonder she had never considered any eligible proposals, had turned a deaf ear to idle talk whether well-meant or malicious. Her heart was already full, to the exclusion of anybody else. ‘No lake can compare with the ocean, no cloud with those on Mount Wu.’ Remembering those lines I often reflected sadly that few people in real life could love like this. No one would love me like this.” (210)

“The Family on the Other Side of the Mountain” (1957, translated 1998)

By Zhou Libo (m.)

Translated by Yu Fanquin

Mr. Zhou presents a very quiet, uneventful story of a journey of guests to attend a wedding in a nearby village. The wedding itself is traditional and the narrator seems to take great relish in finding each promised element is ultimately fulfilled. As timeless as the ceremony is, Zhou reveals the influence of politics via references throughout to the co-op and the co-op chairman. Ultimately, the co-op chairman uses his opportunity to speak at the wedding to run on for thirty minutes delivering a report on the PRC and news of the world. The guests whisper their frustration. What does this have to do with the wedding, the couple, or the village? Worse, the guests discover that the groom is so put off by the bloviating of the chief that he has absconded to the basement, where he used his time more wisely, inspecting the storage of the sweet potato harvest.

“Once girls gather in groups they laugh all the time. These now laughed ceaselessly. One of them even had to halt by the roadside to rub her aching sides. She scolded the one who provoked such laughter while she kept on giggling. Why were they laughing? I had no idea. Generally, I do not understand much about girls. But I have consulted an expert who has a profound understanding of girls. What he said was ‘They laugh because they want to laugh’…I thought this was very clever. But someone else told me that ‘although you can’t tell exactly what makes them laugh, generally speaking, youth, health, the carefree life in the coop, the fertile green field where they labor, being paid on the same basis as the men, the misty moonlight, the light fragrance of flowers, a vague or real feeling of love…all these are sources of their joy.’” (220)

“Three Sketches”

By Zhao Da-nian (m.)

Translated by Wu Ling

Mr. Zhao gives us three pieces of micro-fiction, all on the theme of the artist and creation: “An IQ Test,” “Impression of Drunkenness,” and “Breaking an Eagle.” The first involves a television studio’s attempt to capture three sets of subjects as they solve a new intelligence test. They study a group of party officials, a university seminar, and a first-grade class. Needless to say, Zhao pokes fun at both testing and the PRC. In the second, a painter struggles with the theme of drunkenness. When all his efforts fail, his wife recommends he switch to subjects suitable to the new political climate: satellites, factories, or “Reagan’s visit to China.” In the final story, a frustrated playwright flees the bureaucracy of the big cities for the freedom of the Mongolian grasslands. There, he witnesses the capture and disturbing training of a hunting eagle.

“Before long there was a young cock eagle circling above the roof. It wanted to eat the hare gut and after taking good aim, dived down like a fighter plane, skimmed across the roof, grabbed the gut with its powerful talons, and dragged the five-foot-across basket up into the sky, too.” (“Breaking an Eagle” 234)

“The Tall Woman and Her Short Husband” (1982, translated 1998)

By Feng Ji-Cai (m.)

Translated by Gladys Yang

Feng tells the story of an unlikely romance undone by neighborhood gossip and the Cultural Revolution. The villain is the wife of the “honest tailor” of “Unity Mansions.” A perpetual busybody, she is a stereotypical gossip and the kind of woman whom party officials would eventually use to monitor and report on all activity involving the dozens of families living in the neighborhood. She leads a cadre of jealous wives who are agitated by the happiness of the physically mismatched couple. When the Revolution comes to “Unity Mansions,” the Short Husband is arrested: as a highly-educated electrical engineer, he is sacked from his job and sent down to the country for reeducation. His house is raided, all their possessions are redistributed as public property, and his tall wife is forced to sleep in the tiny guard house. Afraid for her child’s safety, she sends him away to be raised by relatives. Can the couple survive malice and political upheaval?

“She seemed dried up and scrawny with a face like an unvarnished ping-pong bat. Her features would pass, but they were small and insignificant as if carved in shallow relief. She was flat-chested, had a ramrod back and buttocks as scraggy as a scrubbing board. Her husband on the other hand seemed a rubber roly-poly: well-fleshed, solid, and radiant. Everything about him—his calves, insteps, lips, nose, and fingers—were like pudgy little meatballs.” (238)

“The Distant Sound of Tree Felling” (1990, translated 1998)

By Cai Ce-hai (m.)

Translated by Yu Fan-qin

Yu focuses on a tight feudal relationship in a valley undergoing hydroelectric improvements. The primary characters are old Gui, a master carpenter and widower, his daughter Yangchun, and Old Gui’s apprentice, Qiaoqiao. Capitalizing on both his reputation as a master carpenter and the beauty of his young daughter, old Gui has taken advantage of many young apprentices. But when he meets Qiaoqiao, he discovers a man much like himself: obedient, mum, and uninspired. He promises that when at last Qiaoqiao achieves mastery of his craft, old Gui will give him his daughter. Then they will all live together. Of course, in the interim, they live together as well, with the father sharing a room with his daughter, who is now twenty-three years old. When stoneworkers come to blast away the cliffs of the valley and construct offices and living quarters for the future electric works, Yangchun takes an interest in this new craft. She discovers that the foreman of one of the crews is a former apprentice of her father, Shuisheng. Shuisheng hated the controlling old man and is thrilled to find himself a master of a new craft and a respected foreman. Yangchun expresses a desire to learn this trade, inspired in part by bricklayers she knew who were married and worked together; Yanchung loved that they called each other “master.” Meanwhile, she grows lovelier by the day and longs to begin her own life.

“The men had strong arms and legs as if born to lift big stones. They were careless and casual, laughing and whistling, putting the irregular stones into neat walls which were growing like a honeycomb. What they were doing was more interesting and grander than the houses her father and Qiaoqiao built. She wanted to lift a stone, too, imagining that she was one of them.” (257)

“Six Short Pieces” (1996, translated 1998)

By Bai Xiao Yi (m.)

Translated by Carolyn Choa

Mr. Bai presents a series of short tales of love, many of them focusing on the intersection between the public and the private in revolutionary China. The titles are: “Romance,” “Normal,” “Suspicion,” “No Title,” “Madness,” and “Diplomatic Relations.”

“Sometimes it felt as if our passion had become a mystery even to ourselves. By then people were beginning to guess at our secret and tried to ambush us with great determination. Our rendezvous seemed not to be a private matter anymore, but something central to the survival of the whole community. Our happiness and their frustration had somehow become inextricably linked.” (“Madness” 272)

“One Centimetre” (1991, translated 1998)

By Bi Shu-min (f.)

Translated by Carolyn Choa

Bi’s story is told from the perspective of a hard-working, economizing mother of a single son. As he has matured from a toddler to a little boy, she is acutely aware that he has a finely-tuned sense of justice. He watches her, and knowing she is observed, his mother seeks to achieve greater and greater levels of righteous living. When she rides the bus with him, he quarrels with her. Why doesn’t she purchase a ticket for him? The boy is simply too short: children under 110 centimeters require no ticket. But this stings the boy’s pride. To appease her child, she purchases a ticket for him and lets him hold both. Her child’s height becomes a flashpoint again when a neighbor gives her a five-yuan ticket to visit a Buddhist temple. He assures her that the 110 centimeter rule is enforced at the temple. When she arrives, the martinet at the entrance gate refuses to allow the child to enter: the 110 centimeter line is level with the boy’s eyes. But the ruler must be incorrect! And the mother does not have an additional five yuan to spend. Humiliated in front of her son, and suddenly realizing that her boy no longer respects her, she struggles on, a shell of her former self.

“Tao Ying tries to smooth [his hair] down as if she is brushing away topsoil to get to a firm foundation. She can feel the softness of her son’s skull, rubbery and elastic to the touch. Apparently there is a gap on the top of everyone’s head, where the two halves meet. If they don’t meet properly, a person can end up with a permanently gaping mouth. Even when the hemispheres are a perfect match, it still takes a while for them to seal. This is the Door of Life itself—if it remains open, the world outside will feel like water, flowing into the body through this slit. Every time Tao Ying happens upon this aperture, she would be overwhelmed by a sense of responsibility.”