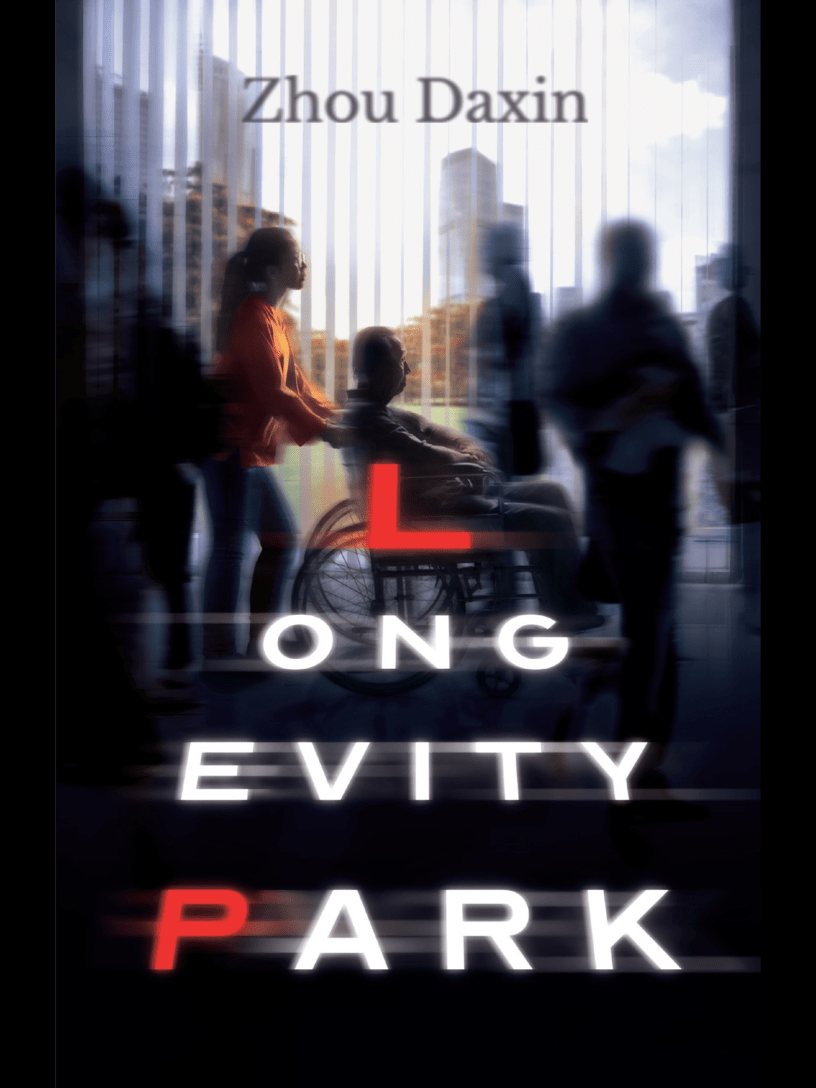

Longevity Park

By Zhou Daxin

Translated by James Trapp

(2021)

Sinoist Books

Perhaps it should not be surprising that countries steeped in Confucian culture should produce so many novels addressing the medical treatment, psychology, and emotional needs of the elderly. Longevity Park by Zhou Daxin approaches the topic of aging from a practical, problem-solving point of view that seems to offer a parody of China’s socialism with special Chinese characteristics where every moral quandary can be solved if one can only just throw enough money at it. As readers, we are on a tour of Longevity Park, a state-of-the-art center for aging that offers the latest treatments for those who wish to preserve their current health and quality of life and extend their lives in order to enjoy many additional years of good living with their families. As we turn the gleaming facilities, we attend slick multimedia presentations on various plans on offer. For example, Longevity Park also provides round-the-clock care for those suffering from the first stages of early-onset dementia. In addition, although Longevity Park hires only the most high-trained and responsible caregivers, families can supplement their loved one’s care by leasing charming robotic nurses whose speech, facial features, and mannerisms are designed to put patients at ease. Then, rather unexpectedly, Zhou shifts gears. The lab-coated sales staff introduce a demure middle-aged woman who introduces herself as an unmarried woman who took up a position as an in-home caregiver for a retired judge. There is some urgency in the family’s search, as the man’s wife had passed on, and his only daughter, who has recently married, is due to leave soon to live in the United States. To her great good fortune, the earnest nurse finds herself hired on the spot. She comes to know the judge very well, and his daughter too, primarily through the daughter’s attempt to set her father up with a new wife. Through this process, the nurse finds herself being drawn into the family itself, operating as a spy for the distant daughter, and a negotiator between two elderly people who may or may not want to begin a new relationship well into their eighties. The structure of Zhou’s novel is unexpected. The first thirty pages might be about hucksters pushing a fountain of youth and silicon valley types offering androids to adult children who might rather not have to clean up after the failing minds and bodies of their geriatric parents, but then Zhou is off, diving deep into the life of the humble caregiver upon whom has been placed the burden of holding together a long-broken family. There is also a subplot where the aging judge enlists the barely-educated country nurse to assist him in writing a multi-volume legal analysis of the social and gender-based forces which lead to criminality and an overview of Korean law. Zhou keeps us intrigued with the on-again, off-again marriage plot, but the true drama unfolds as the soft-spoken, tenacious nurse finds herself taking on the role of a private therapist to the daughter calling from America, and an increasingly fierce defender of the judge’s fading health. Before long, the caregiver is going to increasingly extreme lengths to carry out her duty to the judge. The interplay between the odd cast of characters is consistently endearing, lively, and unexpected as each continues to behave contrarily and make bad decisions. Throughout it all, the resilience of the nurse never wavers. She all but disappears into her service. What inspires the nurse’s devotion? Is she even real, or is she a female Lei Feng, the mythologized ideal soldier who sacrifices all for the greater good and becomes a kind of secular saint? Zhou presents us with puzzle after puzzle about service, the desire to create a legacy that lives on after us, and the pursuit of a life without end.

“I couldn’t work out how old the woman was, nor what she looked like, but judging by the way Uncle Xiao spoke to her, she had to be younger than him. When he spoke to her, his normally rather forceful manner of speech became more careful and thoughtful, and his tone of voice even sounded coaxing and placatory. From all this, I reckoned that the woman must be quite comfortably off; that he was happy with her; that he was courting her good opinion; and that he was definitely her suitor.”