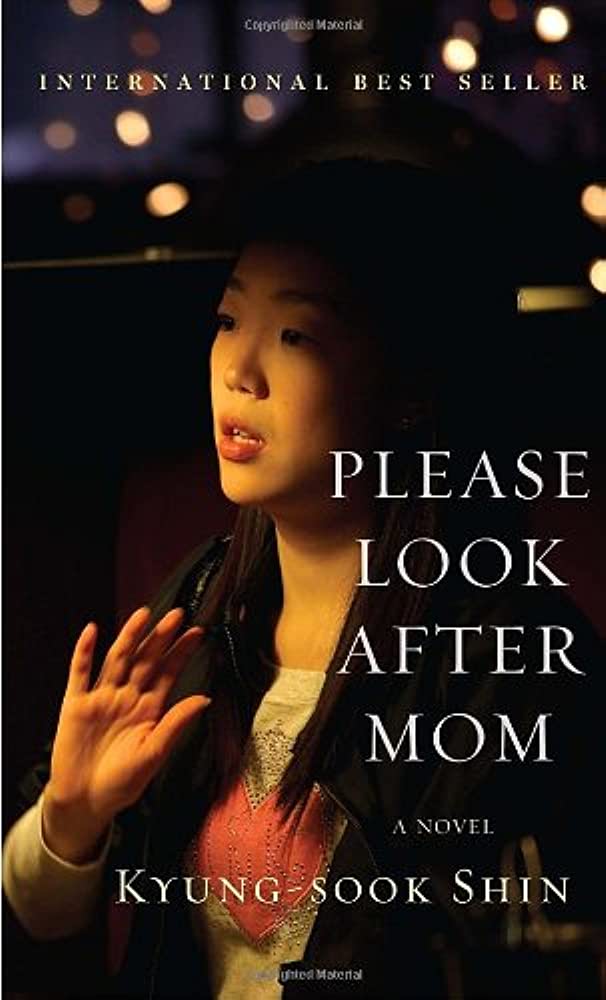

Please Look After Mom

By Kyung Sook-Shin

Translated by Kim Chi-Young

(2008, translated 2011)

Vintage Contemporaries

(Novel)

Kyung Sook-Chin’s novel was an immediate best-seller in South Korea. Her story begins at Seoul Station with the arrival of sixty-nine-year-old Park So Nyo and her husband. Somewhere between getting off the train and before connecting with the family, Park So Nyo disappears. Terrified for her safety, the family searches through the station but finds it difficult even to give an accurate and useful description of their mother. In the weeks and months that follow, each family member contributes to the search for their mother while also reflecting on their relationship with the self-effacing matriarch. The reader learns about the absent mother through the troubled memories of her husband and children; by the midpoint of the story, we realize the deep isolation of the mother as well as some of the secrets of her inner life. Each of the characters experiences self-recrimination for their conduct toward Park So Nyo; some emerge from the ordeal having grown a greater awareness of the kind of lives they want to live and the people they want to be. Throughout, Ms. Kyung contrasts the post-war poverty the family endured against the cold steel apartment buildings her children inhabit. Like many novels about the post-war generation, Kyung focuses on the Korean generational gap, where one side is agrarian, religious, and still deeply affected by decades of hardship, poverty, and the trauma of modern civil war, and the other side consists of citizens who have benefitted from rapid economic growth offered by “The Miracle of the Han” yet find themselves so overworked and so limited in their careers that they are almost completely denied their ability to focus on themselves and their families.

“When you write July 24th, 1938, as Mom’s birth date, your father corrects you, saying that she was born in 1936. Official records say that she was born in 1938, but apparently she was born in 1936. This is the first time you’ve heard this. Your father says everyone did that, back in the day. Because many children didn’t survive their first three months, people raised them for a few years before making it official. When you’re about to rewrite “38” as “36,” Hyong-chol says you have to write 1938, because that’s the official date. You don’t think you need to be so precise when you’re only making homemade flyers and it isn’t like you’re at a government office. But you obediently leave “38,” wondering if July 24 is even Mom’s real birthday.”