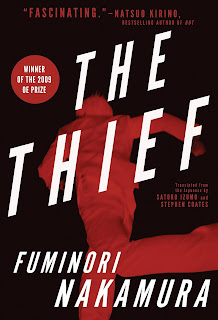

The Thief

By Nakamura Fuminori

Translated by Satoko Izumo and Stephen Coates

Penguin Random House

(2009-translated 2012)

Soho Crime

Nakamura’s stock in trade is the first-person narrator, short-form crime novel. Narrators tend to be criminals, sometimes psychotic amateurs, sometimes seasoned professionals. In The Thief, Nakamura takes us into the mind of a pickpocket working the crowds outside tony venues and bullet train platforms. Unlike most members of his trade, he works alone. He targets wealthy men, dipping slender fingers into jackets or slicing the bottom of a pocket with his knife. The all-but-nameless protagonist appears to be living a life of extraordinary freedom combined with a bottomless cache of good fortune. When we first join him, he speaks with a connoisseur’s confidence and certainty, directing our attention to the bespoke tailored suits and shoe brands favored by the elite. He hints that he is not simply a common thief and proves he is something of a Robin Hood or avenger of the weak; however, the hero’s narrative starts to fray at the edges. Here and there, a female face in the crowd reminds him of a lost love, and challenging targets cause him to ruminate on the recent disappearance of his partner, who, if he isn’t dead already, must be in the gravest possible danger. More troubling still, he is hallucinating, seeing a tower where there is none, a haunting architectural presence that might appear outside the window of a train or far on the horizon. He has sensed the structure before, in his youth, but the sightings have lately become more frequent. And when he checks his pockets, he finds wallets he has no recollection of taking. Thus, although there is an element of the fantastic in his skill, it soon becomes apparent that he is not in control of his stealing, as much a slave to his work as the salarymen and drug addicts he mocks. Following him, we see a man who almost experiences an erotic intoxication through each successive crime, but in every instance, the fever passes and he remains unsatisfied. Liken the faceless consumers who seek to find some sense of release or relevance by making their next purchase, the thief is never not stealing, dumping wallets and credit cards where they may find their way back to their owners and spending the cash almost immediately. He purchases clothes to disappear among certain crowds and then disposes of his disguises in subway restrooms before he returns to his thieving. As on the edge as he is, the thief, who may be in his late twenties or early thirties, seems to be just now recognizing his meaningless existence and his existential loneliness. He becomes involved with a battered prostitute and her young son, but just as we begin to see the hero imagine a life apart from his obsession, an associate ropes him into a high-stakes break-in meant to intimidate an old man and his mistress. Though the crime is successful, the pickpocket’s life goes sideways, but because the ring leader, with nothing more than a glance, sees into the soul of the pickpocket and determines that he is not living as if he values life. The leader, who may be an agent of Fate, a Philosopher Thief, or, a sociopath, attempts to drive his hapless subject to a philosophical awakening. The curious new man baffles the hero, as he can attribute no brand name to any of the creature’s clothing or accessories, and we are not altogether certain that the pickpocket catches the cipher’s blunt reference to Dostoyevski’s Raskolnikov. Nakamura presents us with all the thrills of a crime novel while addressing fundamental questions about capitalist culture, where the proscribed path to self-fulfillment requires the constant acquisition and disposal of cash. The speed of Nakamura’s novel as well as the vivid rendering of all his characters, as shallow as they may be, create a sense of chaotic intimacies that never fully develop, which seems inevitable in this world where the sum of a life might be best measured by a cardboard box full of disorganized receipts.

“The more I stole, I believed, the further I would move away from the tower. Before long the tension of stealing became more and more attractive. The strain as my fingers touched other people’s things and the reassuring warmth that followed. It was the act of denying all values, trampling all ties. Stealing stuff I needed, stealing stuff I didn’t need, throwing away what I didn’t need after I stole it. The thrill that vanquishes the strange feeling that ran down to the tips of my fingers when my hands reached into that forbidden zone. I don’t know whether it was because I crossed a certain line or simply because I was growing older, but without my realizing it the tower had vanished.”