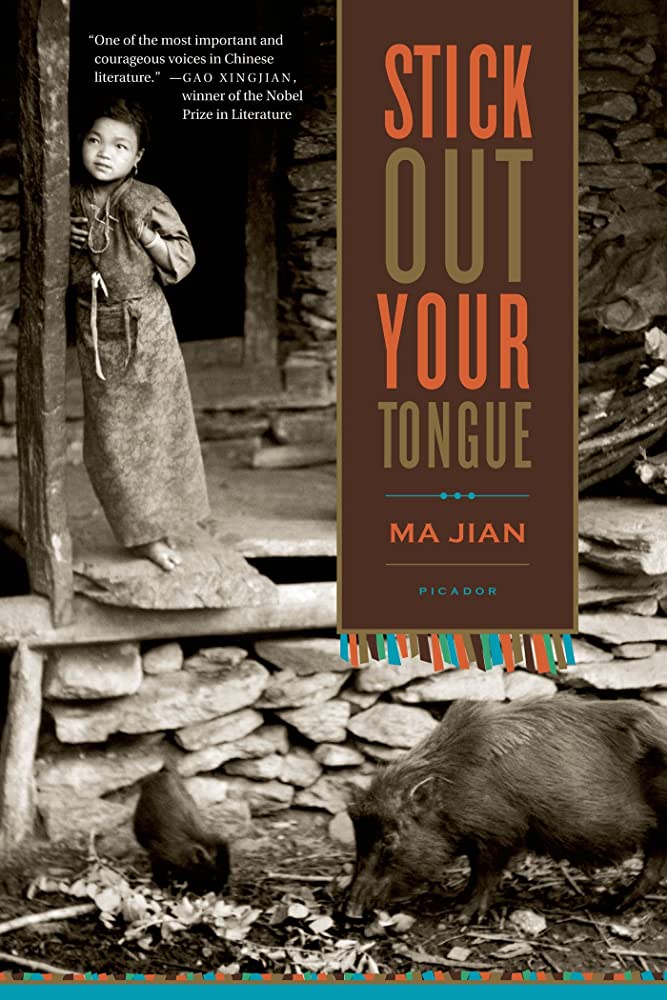

Stick Out Your Tongue

By Ma Jian

Translated by Flora Drew

(1997, translated 2007)

Picador

(Novel)

At first glance, Ma Jian’s Stick Out Your Tongue appears to follow in the footsteps of great spiritual journeys such as Seven Years in Tibet, Wolf Totem, and Soul Mountain, as the writer sets off on foot to explore the Tibetan plateau. The genre calls for an adherence to primitive travel, visiting and living with itinerant herders, fighting against the bitter cold and reveling in the beauty of endless grasslands and towering mountains, and reverencing the ageless culture and faith of the Tibetan people. In Wolf Totem especially, the Chinese traveler goes to Tibet to find the mindset, strength, and courage of the truly heroic nomad from which he or she can trace their blood before the Chinese became an agrarian, sedentary, and civilized people. There will be scenes of being lost in blinding storms, quiet meals of yak butter in darkened tents, exchanges of old tales, gossip, and the ritual of the sky burial, but in every case, Ma Jian will present us with an altogether different view of Tibet, one that is grotesque, degraded, and more profane than sacred. To understand Ma Jian’s journey and his point of view, it is essential to read the “Afterword” of the novel first. In it, Ma explains that he had been evading the police for some three years after a novel he write ran afoul of Chinese censors. In 1985, he decided to flee to Tibet to put some distance between himself and his oppressors and renew his faith in Buddhism. Instead, he discovered the impact of China’s takeover of Tibet in 1950: extreme poverty and a splintered and disintegrating society. He managed to get his book published in China in 1987. It was immediately banned by the Chinese government and Ma fled again, this time to Hong Kong. The stories are dark and joyless, and almost always involve a face-to-face, visceral confrontation with a stomach-churning violation of a taboo. For example, every spiritual account of Tibet features the narrator experiencing both revulsion and awe over the ritual of sky burial. The westerner or the southerner invariably comes to a greater understanding of the nomad’s views on life and death and comes away with a profound reverence for the people and their beliefs. Ma, too, asks for permission to witness this sacred event. What he describes is a complete horrorshow and emblematic of all the tales: “The Woman and the Blue Sky” is the first story in the collection. Ma meets a Chinese soldier who tells him that there is to be a sky burial soon: a young girl, just seventeen, has died in childbirth; the fetus is still inside her. What is more grotesque, the tale of the girl’s life or the brutality directed toward her body at her death? Ma learns that she was sold as a child and that her foster father abused her. She was bought as a wife to two brothers in their forties who spent most of the year in complete isolation. When Ma meets her, she is wrapped in a burlap sack. Ritual, practice, and prayer are not evident. Watching the brothers slice the dead girl’s face from chin to forehead and hurl her bloody scalp into the sky, Ma understands that the child’s life and death are evidence of a dead culture. Each story depicts a similar moral and ethical catastrophe, often focusing on assaults on women or children, and in every case, Ma claims that the primary driver of this devolution and dissolution of Tibetan society and its citizens is Chinese rule. While reading Ma’s account of late 20th-century Tibet, it is possible to recognize acts and points of view that echo the most primitive and violent of the ancient Greek myths or chronicles of The Hebrew Bible. His work is stunning, nauseating, and aimed directly at China’s heartless policy of expansionism.

“Tibet was a land whose spiritual heart had been ripped out. Thousands of temples lay in ruins, and the few monasteries that had survived were damaged and defaced. Most of the monks who’d returned to the monasteries seemed to have done so for economic rather than spiritual reasons. The temple gates were guarded by armed policemen, and the walls were daubed with slogans instructing the monks to ‘Love the Motherland, love the Communist Party and study Marxist-Leninism’. In this sacred land, it seemed that the Buddha couldn’t even save himself, so how could I expect him to save me? As my faith crumbled, a void opened inside me. I felt empty and helpless, as pathetic as a patient who sticks out his tongue and begs his doctor to diagnose what is wrong with him.” (87)