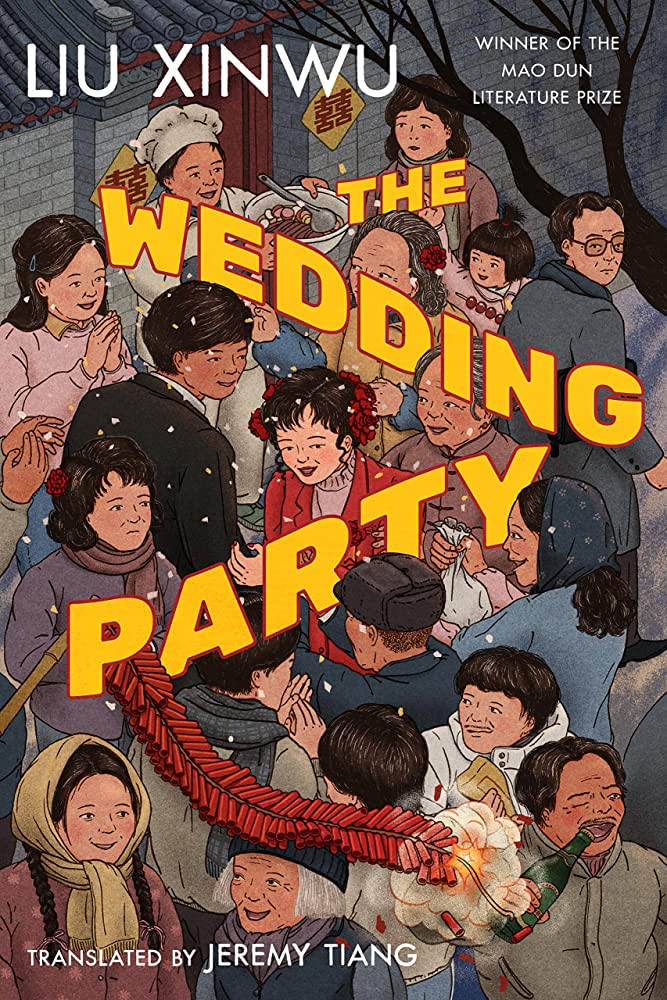

The Wedding Party

By Liu Xinwu

Translated by Jeremy Tiang

(2016, translated 2021)

Amazon Crossing

(Novel)

The Wedding Party is exactly that: a wedding party in a siheyuan courtyard in Beijing. It is Sunday, December 12th, 1982. Liu tells the story of what happens on that day, from sunup to sundown, through the eyes of the major players in the drama: Auntie Xue, on whom the success of the banquet rests, her son, groom Xue Jiyue, and the bride, Pan Xiuya. But Liu sees the event as a communal rite involving immediate and extended family members as well as staff hired to provide food, beverages, and entertainment that day, so it should not surprise readers that the chef, Lu Xichun, will feature as large as anyone else in her account. Liu’s siheyuan is situated within view of the Drum and Bell towers, two majestic and practical buildings erected to announce the time in northwest Beijing. The Drum Tower was completed in the Yuan Dynasty; its name then was the Tower of Orderly Administration. The Bell Tower was originally a part of the Wanning Temple until it was relocated to act in tandem with the Drum Tower. The two towers and China’s long and continuing relationship with time are recurring symbols in The Wedding Party. Liu’s Prologue and Epilogue ask us to consider the various ways her characters envision time in 1982. All of them suffered under the Cultural Revolution, and in 1979 they witnessed the politburo vow to never follow such a program again; instead, the Chinese leadership committed to rapid economic construction, a policy that allowed virtually all of the characters in Liu’s cast to experience a kind of socio-emotional and political rebirth. It is also a time when China’s perception of time is shifting. The older generation acknowledges a cyclical Buddhist time as well as a historical time that is rooted in China’s long distant past. Time is spiritual, full of faith and superstition, and a belief that the destinies of China and its individual citizens have already been written. But others see time as something that can be measured in the cost to families and individuals who experienced the Sino-Japanese War, Mao’s Agrarian Reforms, Rural Collectivization, Anti-Rightist Campaign, The Great Leap Forward, and the Proletarian Cultural Revolution. And so as each character enters the siheyuan to play their role, Liu introduces them as they are now and how they managed to live through so many years of disruption, terror, and suffering. Meanwhile, the younger generation looks to the future. They can all afford digital watches that tell the time with atomic accuracy and are so cheap that they can afford to buy timepieces for their children and grandchildren. For the present, the most significant timepiece is the Rado watch that the bride-to-be demands from her fiancé as a wedding gift. What it means to her and how her husband acquired it is best left to Liu’s detailed and wandering storytelling. However, the watch plays a central part in the drama of the day when both the watch and a red envelope containing a gift for the chef, “the soup envelope,” go missing. It happens in the chaos of guests and workers entering and exiting the party. When alerted of the theft, the bride locks herself in her bedroom, and Auntie Xu, the matriarch on whose shoulders the success of the wedding banquet and the reputation of the family rest, attempts to solve the crime, appease the bride, pay the chef, and restore peace and happiness to the celebration. Some have criticized Liu for her structure, wishing that she could stick to telling the story of the day. If the reader is patient, though, the complex pasts of these many different guests–some of whom are allies, others old opponents–are fascinating embodiments of the history of 20th-century China.

“He never once thought about having any kind of “career”! Did he dream of being commander-in-chief? He didn’t even think about becoming commander of his own company. When he joined the workshop, younger men often asked him, “Why did you come home after the war? If you’d stayed in the army, you might be a deputy commander by now.” There was some truth to this—some of those who joined up at the same time as him had now climbed as high as lieutenant general. Even so, Xun Xingwang had no regrets. He was an ordinary soldier on the battlefield, and an ordinary laborer in the workshop. Now he’s an ordinary cobbler on the sidewalk by Houmen Bridge. His blood and sweat flowed righteously, he served his country and his people, his own life is getting better and better, and he’s never done anything that’s kept him up at night. He respects himself and has earned the respect of those around him. What’s wrong with living the way he does? Yet Lei and Wanmei refuse to be content with what they have. All day long, they clamor after this “career,” trying to stand out and rise above others.”