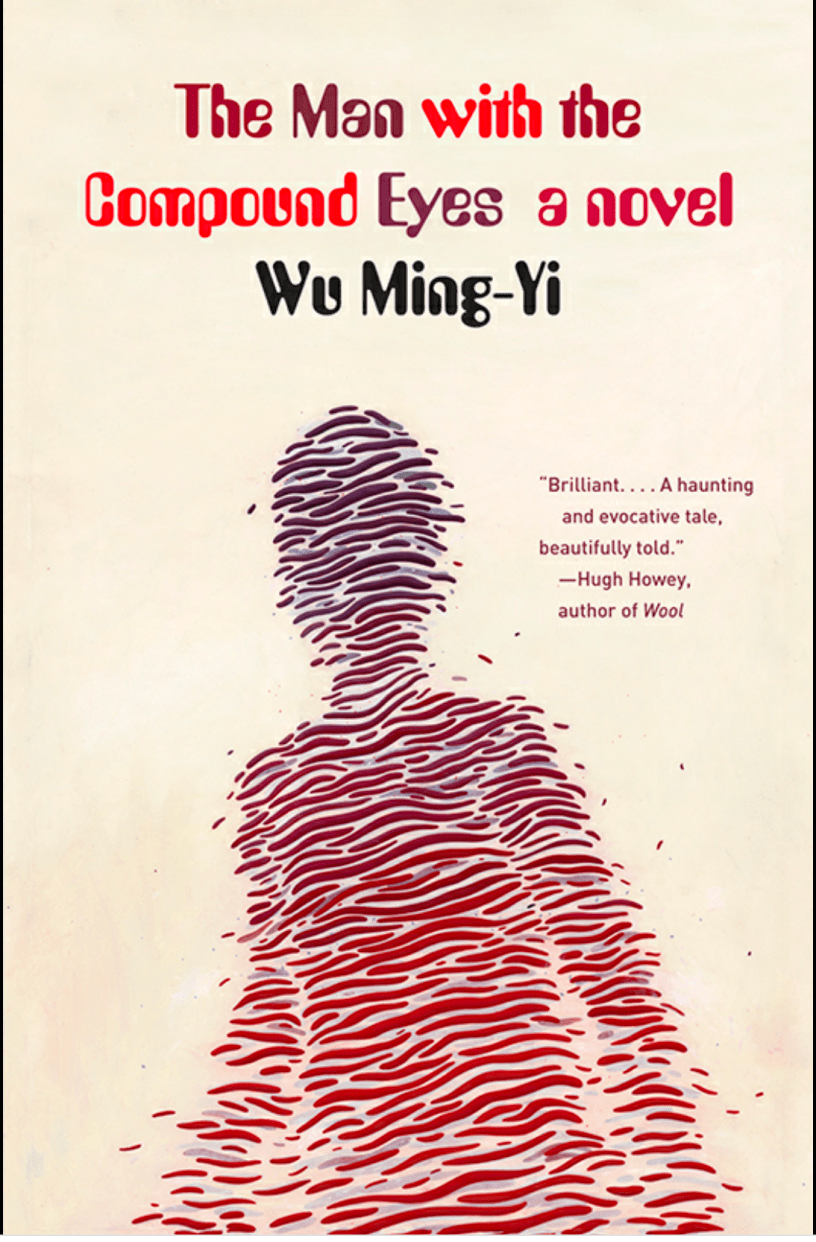

The Man With the Compound Eyes

By Wu Ming Yi

Translated by Darryl Sterk

(2011, translated 2013)

Vintage Press

(Novel)

Wu Ming-Yi juggles multiple plot lines in his portrayal of a globally generated ecological disaster that wreaks havoc in Taiwan. To some extent, the nation suffers the consequences of its own zeal to dominate its natural landscape, best expressed through the journey of a group of engineers investigating reports of dangerous fissures occurring in tunnels bored through the heart of a mountain in order to speed up holiday traffic. A gigantic portion of something like the Great Pacific Garbage Patch has broken off and choked the coastline, invading every cove and inlet with a seething mass of plastic trash. Unlike most plastics of the Pacific vortex, almost every object washed up in the cove can be recognized. Chaotic rains, flooding, landslides, and a horrific storm at sea alter the very geography of Taiwan. The disruption complicates the lives of indigenous people, young moderns, scientists, and eco-warriors. In particular, it threatens to consume a modern home built on a promontory overlooking the sea. It belongs to a Taiwanese woman who married a foreign architect who decided to build it as a gift to his wife. Though providing a breathtaking view from inside the house, the exterior gives it the look of a folly to the locals, and the architect turned a deaf ear when neighbors warned that its location did not take into account the dynamics of the country’s dynamic coastline. Much of the story revolves around the fate of this woman, who is still grieving the loss of her husband and son, who disappeared years before while exploring the most remote region of the island nation. Wu also weaves into his ecological stew the tale of a young sailor who appears to be on a vision quest that originated on a paradisiacal island that could be mythological. In any case, the prehistoric traveler is swept up by the superstorm and washes ashore in the modern age, where he finds protection from the lonely mother, who sees the young traveler as a key to discovering the fate of her lost family. Meanwhile, despite the mountains of garbage that poison every inch of the shore, a cluster of characters emerge. Some are indigenous people, others are foreign immigrants, but amid the chaos that surrounds them, they seek out guides and engage in rituals of purification. Wu’s world is the stuff of fantasy, dystopia, or speculative fiction. His writing is dense and sweeping as he ranges back and forth across the island, back into the pasts of his main characters, and into the increasingly inexplicable and supernatural encounters in the island’s heart and along its shore. It is an exciting text with many endearing characters who use the radical re-creation of physical geography and climate patterns to inspire us to acknowledge where and why we have wounded the earth beneath our feet while also goading us to reopen and finally heal our own self-inflicted trauma.

“Another day, the Earth Sage took the children to the field in the hollow, to the place where the akaba grew. One of the only starchy plants on the island, the luxuriant akaba, a word that meant ‘shaped like the palm of a hand’, seemed to raise innumerable hands in supplication to the sky. The island was small and the people lacked farming tools, so pebbles were piled around the plots, to keep the soil moist and to serve as a windbreak. “You must love the land, my children, and ring it in with your love. For the land is the most precious thing on this island. It is like rain, like the heart of a woman.”