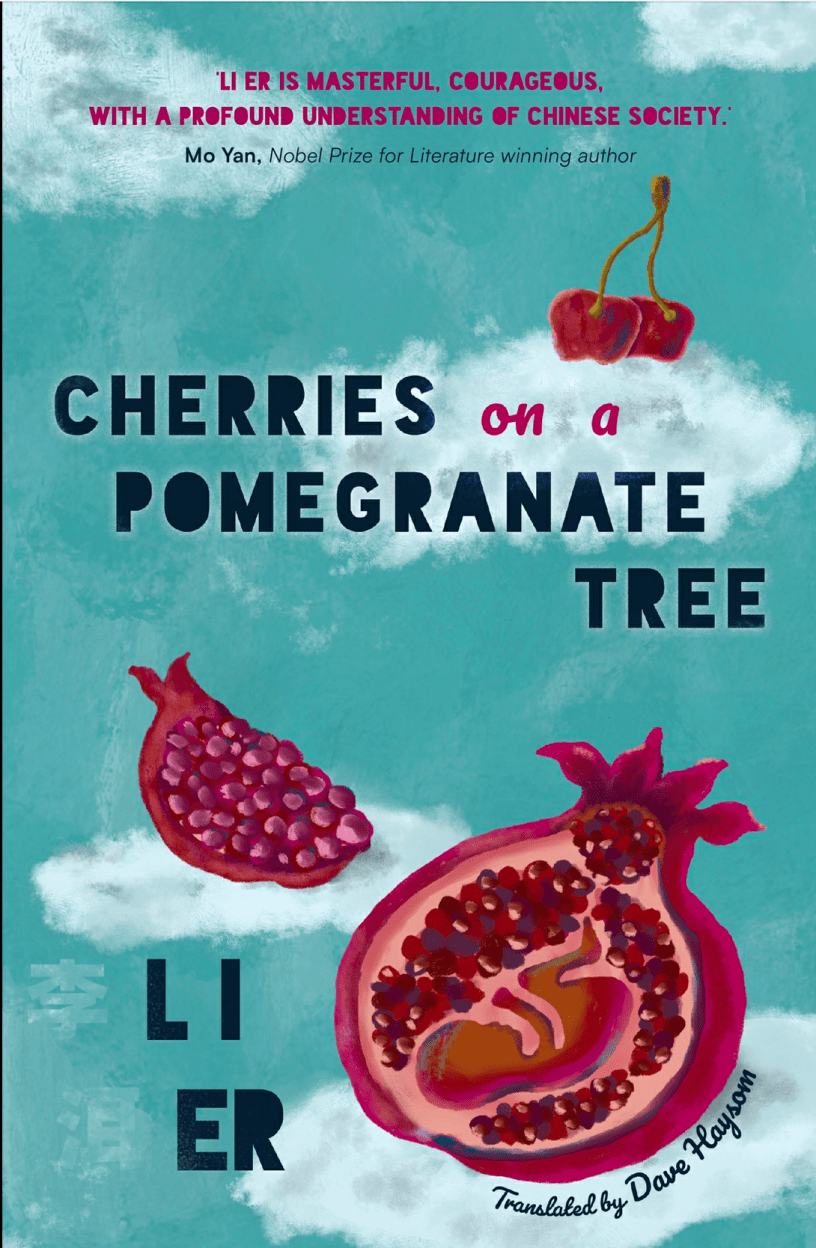

Cherries on a Pomegranate Tree, by Li Er

Translated by Dave Haysom

(2004, translated 2023)

Sinoist Books

(Novel)

The star of Cherries on A Pomegranate Tree, by Li Er, is Kong Fanhua, a wife and mother, a wheat farmer, and the village head of the town of Xiushu. Li reports that the Xiushu River featured large in the epic The Water Margin when it was a powerful force of nature. He also observes that the river has become a slow-moving open sewer and that diminished, polluted water represents the land’s fall from greatness and the muddies, turbid state of contemporary China. body The plot of the novel concerns a series of crises that descend on the overworked Fanhua. In a few days, the citizens of Xiushu will vote for a new village head. As the incumbent, Fanhua has proven to be an exceptional politician, resolving squabbles, and even taking the local paper mill to task for its poisoning of the river. She is proud of her work, but she is tired. Worse, Fanhua has discovered that one of the women of Xiushu outfoxed the local clinic and is pregnant, a dangerous violation of China’s One Child Policy. The woman has gone to ground, and though the local police are torturing the woman’s husband, he refuses to divulge his wife’s whereabouts. Fanhua is partly impressed by the determination and cleverness of the woman in question, but she knows that if she can not find the woman in time and have the child aborted, she will be disgraced and will have no chance at public office. There is also a rumor that a foreigner, someone named Jimmy Carter, is coming to tour Xiushu, so there is a town-wide push to bring the citizens up to speed in conversational English. Finally, Fanhua must deal with her husband. Dianjun spends most of the year in Shenzen working in a shoe factory. He imagines his productivity will make him another Lei Fang, but Fanhua finds her once-handsome husband a slacker and a dreamer, and she is concerned about his new scheme to introduce camels to Xiushu and make camel-skin shoes. Li Er’s heroine is a wily and resourceful problem solver. We follow her as she makes her rounds, chastizing laggards and settling petty disagreements. However, Li truly shines with scenes depicting Fanhua interacting with local politicians, entrepreneurs, and swindlers. Negotiations are exquisitely indirect. Perhaps because it is too risky to ever admit how they feel about one another or about the government, everyone in the novel speaks in codes. Some are from Confucius or The Water Margin, but most are straight from the farmyard. The characters are living in a rural community that is fast moving into the 21st century. Some of the flashier citizens drive Beijing Hyundais, but everyone speaks, schemes, and struggles for power through the language of proverbs. To succeed in Xiushu, individuals must deploy proverbial phrases with subtlety and parse the responses carefully, as in this example:

“And if it doesn’t work out?”

“It doesn’t matter if it works out or not. We still need to make an effort to keep pushing things forward. We might get our hands on some jujubes or we might not, but we’ll never know unless we start whacking the tree with a stick.”

“But if it doesn’t work out,” Xiangsheng persisted, “even after the money’s been spent. What then?”

Fanhua could see the calculations happening in Xiangsheng’s head. He was angling for the power to spend money freely, in a way that would be impossible for anyone to track. He was a businessman all right, trying to figure out how to skim some money for himself before they’d even started.

“Well, naturally you’ll need to be supplied with a stick to knock down those jujubes. You can spend away, and so long as everything’s properly itemised then there’ll be no problems with reimbursement, right?”

“Well then, I suppose I can try.”

“Try?” said Fanhua. “What do you mean, try? I’m entrusting you with this job. What is it they say in the old play? A general in the field makes his own rules. If you can pull this off, then the whole of Guanzhuang will owe you a favour.”

The folksy brinksmanship is a delight, but there are other ways to get your point across in Xiushu. One of the most unexpected is the frequent use of “upside down songs.” Fanhua’s own mother taught this upside down to her daughter Beanie:

Back-to-front, inside-out,

Stones in the river roll right out.

Just one star in a sky of moons,

A million generals in one platoon.

You must never ever sing this song,

Else you’ll hear a deaf man laughing along.

This particular upside-down song is innocent, but Fanhua and others use the genre to skewer their political foes. The multiple crises are all resolved in one way or another, but much of the joy to be found in Cherries on a Pomegranate Tree lies in Li Er’s ability to highlight the ways the citizens of Xiushi use agricultural proverbs, literary allusions, and schoolyard rhymes as a language for challenging authority or speaking the truth. Li has created a memorable town full of over-the-top characters, one I’ll be eager to revisit before too long.