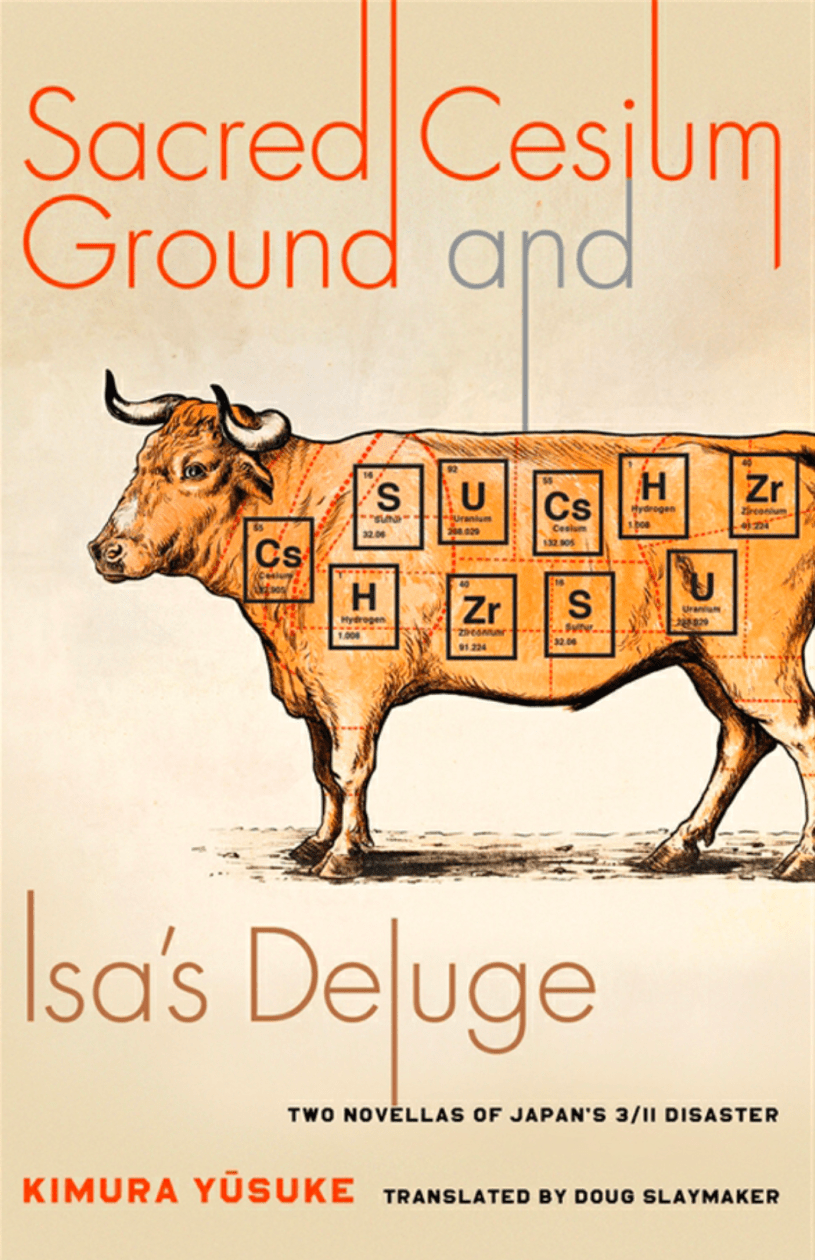

Sacred Cesium Ground and Isa’s Deluge

Two Novellas of Japan’s 3/11 Disaster

By Kimura Yusuke

Translated by Doug Slaymaker

(2014 and 2016, trans. 2019)

Weatherhead Books on Asia

Columbia University Press

For newcomers to Japanese literature and those interested in the emotional and psychological impact of the triple disaster of 3/11 and its aftermath, Kimura’s novellas are essential reading. The first, Sacred Cesium Ground, addresses the government’s decision to abandon or destroy all animals left in the areas affected by flooding and irradiation. Here, Kimura builds his fiction on the foundation of a real-life hero, Yoshizawa Masami, who returned to irradiated land to provide feed and veterinary care to hundreds of cattle who were left behind. Yoshizawa Masami’s efforts and his farm, which he named “Hope Ranch,” caught the imagination of the Japanese public, and he became a powerful and charismatic inspiration for people across Japan. In this story, a neglected and physically abused wife leaves her husband and her empty life in Tokyo to volunteer at a ranch that provides care for irradiated cattle. We journey into the hot zone alongside the troubled heroine, who discovers that the heroic man who runs the program is more complicated than television reporting makes him out to be. In addition, she learns that despite the public enthusiasm for his work, very few people have actually volunteered or sent money to support the mission. Like the cattle, she becomes mired in waste that no one has time to remove and works to exhaustion to feed hundreds of cattle with fodder that is insufficient and moldy. Just as the Japanese public turned the leader into a rock star, they elevate certain of the cows, turning them into angels or martyrs representing the entire herd. The hero also witnesses the press junket of a popular young politico who uses the cattle farm as a backdrop to her campaign. Kimura emphasizes the gulf between the few humans who actually risk their lives to provide care for the animals and the citizens of Tokyo who are able to engage in a kind of performative empathy and thus reassure themselves of their perhaps shallow love for the sick and the dying. His heroes also argue that the government’s half-hearted response to caring for the animals represents their eagerness to forget the disaster and erase it from popular memory Likewise, In Isa’s Deluge, Kimura exposes the degree to which the people of the Tokuhara region feel neglected and abandoned by the citizens of Tokyo. In this story, a young man who is drifting through temporary jobs in Tokyo begins having dreams of his notorious Uncle Isa, a squid-boat worker prone to brooding, alcoholism, and violent rage. Troubled by the recurring dreams, he decides to finally visit his family, who work in the fishing industry. At the time of the triple disaster, he convinced himself that his family was in a relatively safe zone and assumed they got off lightly. When he arrives, he is ashamed to discover the high watermark on the outside wall of their home and witness the extent of the devastation. His shame grows as he walks through the old neighborhood on his mission to interview family members about old Isa. He grows to admire Isa more and more, discovering that he came from the north and seems to be connected to the Emishi indigenous people. As his investigation continues, Isa returns again and again in his dreams, as if he is an ancestral spirit attempting to guide and direct the directionless young man. He concludes, as several of his friends who live in the flood zone, that they need to leave behind their tendency as Japanese to accept their fate and submit to trust authority and instead release their rage on the government and the people of Tokyo. Kimura’s characters argue that they provide the power and the food to sustain the citizens of Tokyo without enjoying any of the economic benefits, while their fellow citizens refuse to make even the smallest sacrifice, not only failing to provide labor or economic support but also continuing to demand cheap electricity and food at levels that are gluttonous and immoral.

“The first time the people of Tohoku joined hands was to fight the imperial forces led by western clans in the Meiji Restoration wars of subjugation, but they lost then too. In other words, again and again losing to the western part of the country. Somebody, I don’t remember who, once talking about ‘north of Shirakawa, one mountain is worth a single dollar’ and wrote the whole area off as valueless with a few words, as a region that is dark and cold and poor. And we thought of our area the same way, living our lives burrowing around silently in the dark.… That’s been us, always keeping to ourselves, should’ve raised our voices, should’ve made noise about all this.”